An Arizona lawmaker helped spark a discussion in the Legislature by proposing a bill that could make altered or enhanced printed advertisements illegal in the state.

Katie Hobbs, a Democrat from District 15, proposed House Bill 2793 last month. The bill, which was discussed in the House Commerce Committee on Feb. 15, would require any manipulated advertisements to include a disclaimer.

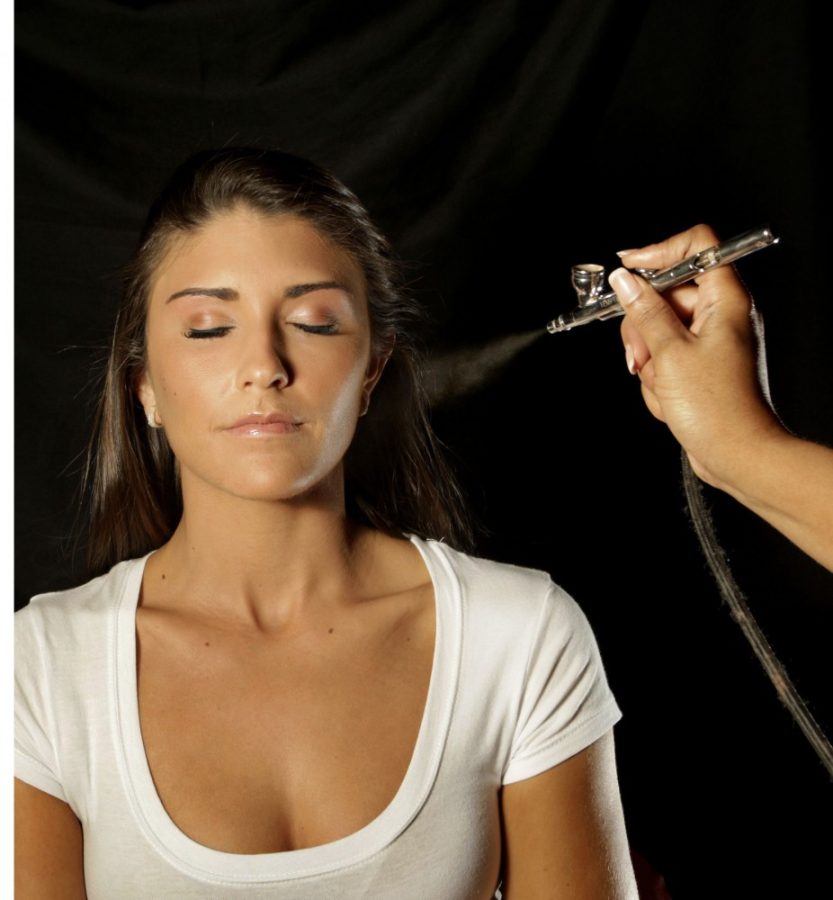

The bill targeted beauty product advertisements that use techniques like airbrushing to make photos of men and women more appealing. While the bill didn’t see a vote this session because other legislators found it too regulatory, it may be reintroduced in following years. It has also provoked a discussion about false advertising and media’s influence on consumers, especially women.

“There’s tons of statistics about mental health issues in girls and women and just the correlation between the numerous images they see every day that basically tell them they need to be perfect to be valued in society,” Hobbs said. “If there was a disclaimer on the ads they would know, ‘OK, they’re not necessarily telling the truth.’”

Many advocacy groups like the National Organization for Women Foundation and the National Eating Disorders Association claim mainstream media create false images of women that are impossible to live up to. These ideals can cause women and girls to think their bodies are unattractive, leading to diminished self-esteem.

“I get the impression sometimes that people will only listen to me if I look pretty,” said Chelsea Hendryk, a psychology junior and member of the UA V-day Vagina Warriors, a club that addresses violence toward women and girls. “I just feel like we’re trapped in this reality that a woman’s beauty is as or more important than her credibility.”

False ideals created by ads have also been associated with eating disorders, with some claiming that having a negative body image causes women to pursue unhealthy diets. In fact, 34 percent of women say they are willing to try a diet that poses a slight risk to their health in order to lose weight, and 80 percent say images in the media make them feel insecure about how they look, according to a poll conducted by People magazine.

“I think that there’s the message in a lot of this kind of advertising that appearance is linked to happiness or finding love or being successful in life, so a lot of products really use certain kinds of bodies or appearances to kind of sell that idea,” said Kathe Young, a psychologist at the UA’s Counseling and Psychological Services. “So it’s not only maybe causing a girl or a young woman to feel dissatisfaction with her own body but to feel like, ‘I have to do something about that. I have to change my appearance.’”

It is this correlation between low self-confidence, eating disorders and marketing techniques that has prompted Hobbs and others to seek regulations in the advertising industry. One online women’s magazine, Off Our Chests, has started a nationwide campaign to promote what it calls the “Media and Public Health Act.” Much like Hobbs’ proposal, this act would require advertisements that have “meaningfully changed the human form” to include a label stating the images have been changed. Similar legislation has also been passed in the United Kingdom.

“This is just about making the images real,” Hobbs said. “So you might still have really skinny people with flawless skin, but at least you know that they’re real and not these computer-generated or airbrushed images.”

Despite these initiatives, some believe the relationship between media and body image is reversed.

“We (advertisers) are holding a mirror up and saying this is what you as a society accepts,” said Ed Ackerley, a professor of advertising and marketing in the Eller College of Management and the owner of Ackerley Advertising.

Consumers create standards based on the common expectations of their communities. Media reflect these norms, they do not create them, Ackerley said.

Hobbs disagreed.

“Of course an advertiser would say that,” she said, laughing. “They’re selling a product, but to sell that product, they sell an image, and it’s an image that people want but isn’t necessarily attainable.”

The media doesn’t trick people into purchasing certain products, Ackerley said. Consumers know what they’re buying, and being told that photos were altered won’t stop them from spending their money.

“The consumer is pretty smart,” he said. “They realize we’re only telling half of the story.”