Whether or not college athletes should be paid to play is a touchy issue, with strong support on both sides. The issue has the potential to significantly alter the face of college athletics in the near future.

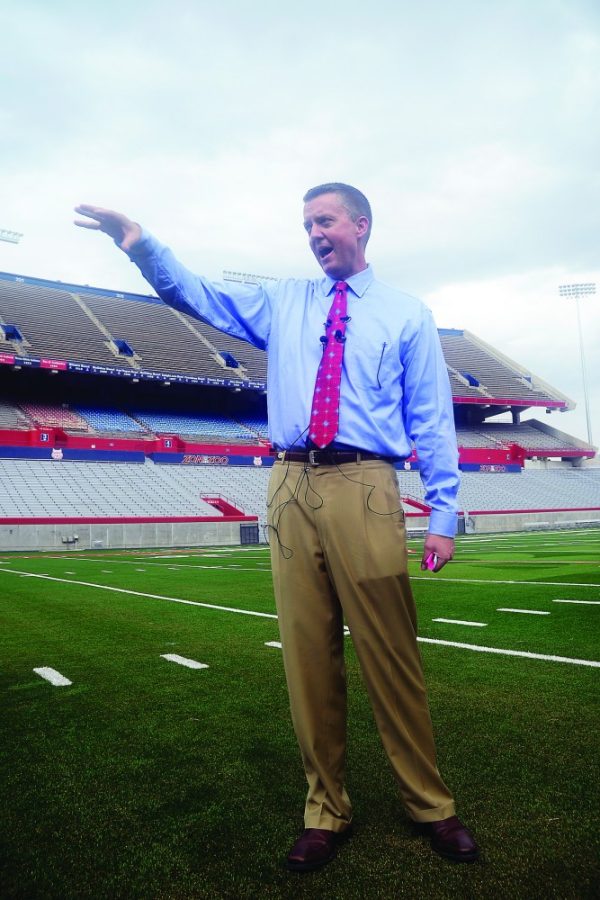

At the UA, athletics director Greg Byrne said that he agrees there are issues with the current system set in place by the NCAA, but believes that a plethora of problems would arise if athletes were paid to play.

“If student-athletes were to be paid, it would dramatically change the face of college sports,” Byrne explained. “If we do [pay athletes], would we just pay football and men’s basketball players? Would that stand up in a court of law from a Title IX standpoint? Would that mean that those players are more valued in your department than your golf team, baseball team or softball team? Those are not easy answers.”

Byrne said he is not opposed to the idea of stipends on top of existing scholarships for athletes.

“I think we always need to look at the experience our students have academically, athletically and socially,” Byrne said. “I know there has been discussion about the idea to implement stipends on top of scholarships to help cover [the] full cost of attendance, and I think that is a worthwhile discussion to have.”

Byrne added that one thing that doesn’t get discussed is the value of the scholarships. Any out-of-state student-athlete who is on a full-ride scholarship will cost the university around $40,000 per year.

“On top [of] the scholarship, [athletes] have the ability to have academic support, strength and conditioning training, team meals, travel and clothing,” Byrne said. “Those are real dollars for us as well. When you start adding those benefits in terms of monetary value [to the scholarship], you can easily get into a situation where the university is providing $75,000-$100,000 a year to support an athlete.”

Not all student-athletes are under scholarship, though, and some believe that compensation for college players is necessary.

“I think there should definitely be a stipend system set up for college athletes,” junior baseball player Joseph Maggi said. “Because of the amount of hours we put in and the dedication we have to our sports, a lot of us don’t have enough time to go out and get a job like normal students do. I know we are not professionals, but we have expenses to worry about and don’t have the same amount of time or opportunities to make money like other students.”

Maggi went on to explain that players who aren’t under scholarship, like most of the baseball team, really feel the hardship.

“Sometimes scholarships aren’t enough,” Maggi explained. “The baseball team only has 11.7 scholarships for 35 guys on the team. That means that more than half the team is expected to deal with the cost of college without the option of working to make money.”

Some have proposed a compromise of allowing players to star in television commercials and obtain monetary benefits through endorsement deals, much like the system set up for Olympic athletes.

“I think the concept is attractive, but the devil is in the details,” Byrne explained. “I do not want our recruiting process to be where if you come to Arizona, we will get you a television advertisement.”

The NCAA defines student-athletes as amateurs, not professionals. While Arizona’s athletics department nets an annual profit, most don’t, and therefore any type of system that attempts to pay athletes would heavily favor existing, fiscally-strong programs.

The money to pay athletes in every sport would have to come from somewhere, and Byrne said the issue is not as simple as it seems.

—Follow Evan Rosenfeld @EvanRosenfeld17