Nearly three years after the United States invaded Iraq and ousted Saddam Hussein, interest in the subject is in no danger of dying down. Every month, bookstores cram the “”Iraq War”” section of their shelves with new additions.

While coverage of the war has been comprehensive, most of these books focus on the big picture. What has been largely missing so far is the kind of personal journalism that has enhanced our understanding of past wars, like Michael Herr’s classic Vietnam memoir, “”Dispatches.””

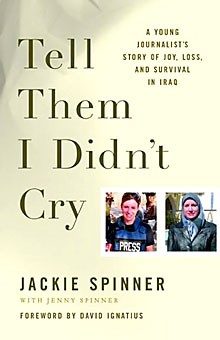

While Jackie Spinner’s “”Tell Them I Didn’t Cry,”” a memoir of her experience in Iraq, doesn’t quite fill that void, it is a valuable book that deserves attention in its own right.

Spinner, a young reporter for the Washington Post, begged her editors for a year to let her go to Iraq, sensing the chance to find her voice as a journalist. She wound up staying nine months, keeping sane by baking cookies for the Post staff, playing soccer and making expensive late-night calls to her twin sister Jenny (who contributes a series of emotional short pieces to the book).

It was a turbulent year for anyone in Iraq, and no less so for Spinner, who barely escaped a kidnapping attempt not long after her arrival.

“”I looked over at the faces in the crowd, and I didn’t see a single person who saw me as a human,”” she writes. “”I tried to plead with a woman standing there, plead with my eyes, and she looked like she wanted to spit on me.””

When it became too risky for her to conduct interviews herself, even disguised in a headscarf and long cloak, Spinner found herself conducting them through a translator while she waited impatiently in her hotel room.

The book is most valuable for its vivid picture of an occupied nation. While most Iraqis were relieved to be rid of their ruthless and sadistic ruler, their relief quickly gave way to anger as they discovered

Tell Them I Didn’t Cry

Jackie Spinner

Scribner

that life in the new Iraq was as dangerous as ever. Where they had once lived in fear of Saddam, now they lived in fear of those who remained loyal to the deposed dictator, as well as the bombs and the guns of the Americans.

Responding to critics who ask why the press never tells us about the good things to have emerged from the war, Spinner writes: “”If the Bronx and Manhattan were being hit daily by car bombs, if tourists from Iowa were being targeted for kidnapping in Queens, but Staten Island and Brooklyn were safe, what kind of stories would we write?””

But there are positive moments. Spinner is captivated by the sight of Iraqi journalists learning to report the facts for the first time, “”the birth of a free press”” after years of censorship.

And she gives us strong, memorable portraits of the Iraqis who work for the Post, most of whom keep their jobs a secret from their families and neighbors, fearing retaliation from insurgents who target “”infidels”” who work with Americans.

Perhaps the most memorable tale she tells is that of the Post’s Iraq office manager, Omar, who was drafted into Saddam’s army a week before the war began. He went to the military base and offered the commander all his money in exchange for a reprieve (bribes were a way of life in Saddam’s Iraq). The commander laughed at him: “”What should I do with your $500? We are going to die anyway.”” The next morning, Omar snuck out of the base and made it back to Baghdad, hiding out in his house until the war was over.

Spinner writes good, workmanlike prose. Sometimes she’s too eager to brush over descriptions, when we’d prefer her to pause a moment and let us absorb the atmosphere, but the freshness and honesty of her voice keeps the book fast-moving and readable.

Critics and supporters of the war alike should find a lot to enjoy in her book.