A UA researcher has shown that the bacteria that causes gonorrhea is potentially able to “recruit” human proteins to protect itself from the immune system.

Nathan Weyand, a research assistant professor at the BIO5 Institute, works with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and a protein called CD46, which inactivates part of the immune system called the complement system. His project has shown that the N. gonorrhoeae bacteria may be recruiting CD46 to protect itself from attacks by the complement system.

“[N. gonorrhoeae is] a fascinating organism,” Weyand said. “It is a current health problem, and each year, there are over 100 million people worldwide infected with this organism. It can cause blindness in children in third-world countries if they’re not treated.”

In addition, N. gonorrhoeae has been growing resistant to antibiotics.

“[It] has been gaining resistance to every antibiotic that has been suggested for treatment, and pretty soon, there may be few antibiotics that will be able to treat it,” said Won Kim, an immunobiology graduate student.

CD46 is a component of the complement system, which is a part of the innate immune system.

“Complement can recognize foreign microbes and it has a way to activate enzymes and attach to foreign microbes, and eventually it punches a hole into the membrane of the invading microbe and this kills the microbe,” Weyand said. “This is an innate defense mechanism our bodies have to protect us from infection.”

Components of the complement system are commonly found in the blood serum and other bodily fluids, and there are over 60 proteins that participate in the complement system.

CD46 is a protein expressed by cells that prevents the complement system from targeting human cells.

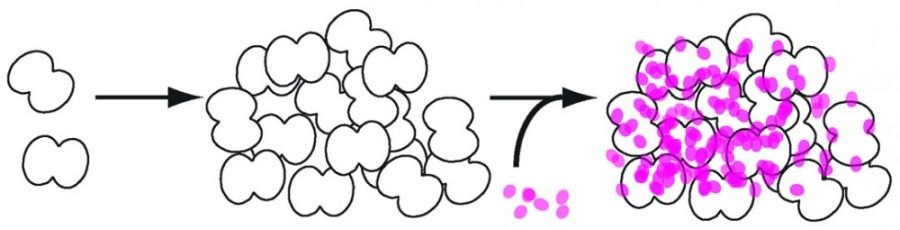

“We’re working to test the hypothesis that CD46, when it is recruited to the site of bacterial adhesion, actually protects the bacteria from complement killing,” Weyand said. “We’ve recently done some microscopy where we see that CD46 stolen from the infected cell permeates the bacteria aggregate. It looks like the bacteria are trying to coat themselves with this human protein that can inactivate human complement.”

In order to study this process in the lab, Weyand has been recreating the steps of infection.

“For our experiments lately, we’ve been infecting human cells with the bacteria, and then after five hours we add a serum, human serum, to the infection, and we see what happens,” Weyand said. “Normally what happens is some of the bacteria begin to get killed by the complement system that is present in human serum.”

Weyand and Kim have been working together to downregulate the expression of CD46 in epithelial cells.

Messenger RNA, or mRNA, are products formed by the template of DNA that contain instructions for making specific proteins. If these “instruction” molecules are destroyed or reduced through a process called RNAi, the expression of the protein is decreased as well.

By interfering with the amount of viable mRNA, Weyand and Kim have been able to decrease the amount of CD46 expressed.

If CD46 recruitment to the site of infection is blocked, the bacteria then become more sensitive to death by the complement system, Weyand said.

“We also use a strain of [N.] gonorrhoeae [that cannot] hijack CD46 as well, and our prediction is that [this strain] will be more susceptible to the complement system,” Kim said.

In people, genetic defects of the complement system may increase susceptibility to infection.

“We think that CD46 plays a role in inactivating parts of the complement system that attach to the bacteria when the serum is there, and that’s what we’re working on understanding,” Weyand said. “What is happening, we think, is that the bacteria are stealing a human protein from the cells and using it to protect themselves.”

_______________

Follow Connie Tran on Twitter.