“As things stand now, I am going to be a writer. I’m not sure that I’m going to be a good one or even a self-supporting one, but until the dark thumb of fate presses me to the dust and says ‘you are nothing’, I will be a writer.”

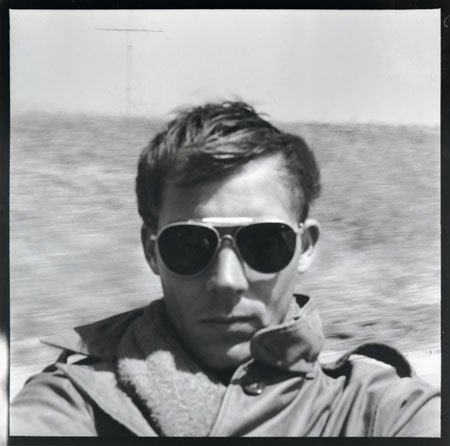

― Hunter S. Thompson, Gonzo

I’ve always had an insatiable appetite for any and all knowledge pertaining to the Sixties. Arguably one of the most gripping decades in modern history, the stark contrast between the beginning and the end of those turbulent 10 years has long piqued my curiosity about the evolution of American values, as well as the contribution those values made to the formation of the counterculture movement.

My fascination with this era ultimately led me to the work of Hunter S. Thompson, an unconventional figure in American journalism and the founder of “Gonzo” style journalism. I was a freshman in high school, determined to delve deep into the study of beatnik literature, biographies about counterculture icons and Vietnam protest songs from the mouth of Dylan himself.

Thompson was a distinct, otherworldly being of sorts, who, to me, seemed omnipotent. He held inaccessible knowledge and used it to create a form of journalism that utilized a frantic and daring first-person narrative style dependent on emotion and satire as opposed to detached, objective reporting. His style of writing was radical in nature, yet still perfectly proportional to the era in which it emerged. I was enthralled.

Thompson was born in Louisville, Ky., in 1937. Unsurprisingly, he was keen on causing mischief from an early age. As a student in high school, he was a part of the Athenaeum Literary Association, often contributing inflammatory and sarcastic submissions to the newsletters. He was eventually booted from the organization in 1955 after a fair number of run-ins with the law.

RELATED: Three UA students and Instagram influencers discuss their journeys with online fame

This, however, didn’t matter. Though he faced jail time for his multiple misdeeds – one of which included robbery – Thompson was honing his literary adroitness all the while, taking shape as the careless, daring rebel the world was yet to make its acquaintance with.

In the years following his jail stint, as well as a brief military career, Thompson worked for several small-town newspapers around the country. Then, in 1965, he caught his big break when he landed an assignment for The Nation, a progressive weekly magazine founded at the conclusion of the Civil War. His task was dangerous, yet fitting: He was to obtain the inside scoop on the Hells Angels, a much-feared motorcycle gang headquartered in San Bernardino. The Angels had recently been tied to a variety of violent crimes, including an incident in which, as Thompson writes,

“Two girls, aged 14 and 15, were allegedly taken from their dates by a gang of filthy, frenzied, boozed-up motorcycle hoodlums … ”

The girls had been brutally sexually assaulted, and the Angels were to blame.

Thompson was introduced to the gang via a mutual friend, effectively establishing trust between him and the tight-knit community of self-proclaimed “one-percenters,” coming from a comment from the American Motorcycle Association that 99 percent of motorcycle riders are law-abiding citizens. Right away he made clear his intentions as a journalist looking to gain insight and perhaps debunk some myths surrounding the infamous cyclists. In his original article, “The Motorcycle Gangs: Losers and Outsiders”, Thompson wrote of the gang’s militant, captivating nature:

“The Hell’s Angels try not to do anything halfway, and anyone who deals in extremes is bound to cause trouble, whether he means to or not. This, along with a belief in total retaliation for any offense or insult, is what makes the Hell’s Angels unmanageable for the police and morbidly fascinating to the general public.”

Thompson’s audacious article garnered immediate success upon its publication. The article was such a hit that he received multiple book offers, prompting him to recommence his Hells Angels escapade. He spent another year growing close with the club’s members, much to the chagrin of his worried wife, Sandy Thompson (now Sondi Wright).

Sondi’s fears weren’t entirely unjustified. Near the end of his time with the Angels, Thompson committed a crucial error when he made an off-handed, critical remark about a member who boasted about beating his wife. In a 1967 interview with author Studs Terkel, Thompson described his brutal encounter with several members of the gang:

“Well, they have a rule, it’s bylaw either 10 or 11, that says, ‘When an Angel punches a non-Angel, all other Angels will participate.’ So I was a victim of either bylaw 10 or 11. I should have known that, though. It was a lapse of caution. All during this stomping, I could see the guy who’d originally teed off on me, just out of, you know, nowhere with no warning, circling around with a rock that must’ve weighed about 20 pounds. I tried to keep my eyes on him because I didn’t want to get my skull fractured.”

RELATED: OPINION: Our ideas about marriage aren’t the only ones out there

Perhaps Thompson’s best known work is his 1971 “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.” The drug-fueled roman à clef tells the tale of Raoul Duke and his attorney, Dr. Gonzo, as they travel to Las Vegas, ruminating along the way on the fiasco that was the 60s counterculture movement. Their main objective, which is to report on the Mint 400 motorcycle race, is continually interrupted by the pair’s prioritization of recreational drugs. One of the most memorable quotes from the book describes the protagonists’ travel essentials:

“We had two bags of grass, seventy-five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multi-colored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers … and also a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls.

“Not that we needed all that for the trip, but once you get locked into a serious drug collection, the tendency is to push it as far as you can.”

The inclusion of frequent heavy drug and alcohol use in his magnum opus was a mirror of Thompson’s own life. His substance abuse was a secret to neither those who knew him personally nor to his many fans, inevitably engendering a disappointing decrease in the quality of his work.

In an interview for Newsweek, Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing” illustrator, Ralph Steadman, looks back Thompson’s “insulting” unconcern for the duo’s task of covering 1974’s “Rumble in the Jungle” fight between boxing greats George Foreman and Muhammad Ali:

“Thompson really didn’t want to watch a couple of guys fighting. He was doing it for the job … All he wanted to do was swim or sleep or take drugs … I said, ‘Are we gonna watch the fight?’ And he said, ‘I sold the tickets, Ralph.’ ‘You sold the tickets?’ He said, ‘If you think I’m gonna watch a couple guys beat the shit out of each other, you got another thing coming.”

RELATED: ‘Dynamite with a laser beam, guaranteed to blow your mind’

Between 1984 and 2004, Thompson contributed to Rolling Stone, albeit spasmodically; he published a mere 17 articles over the 20-year period. In his last article for the magazine, titled “Football Season Is Over”, Thompson expressed disdain with his declining health and the banality of old age:

“No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun – for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax – This won’t hurt.”

On Feb. 20, 2005, Thompson, in true gonzo fashion, committed suicide in his Colorado home.

Though he’s gone, the effects of his idiosyncratic literary style on many of his contemporaries, as well as today’s writers, isn’t. Thompson has taught me, more than any teacher ever has, about the weight and pure power that one’s voice and perspective have the potential to carry.

We mustn’t render even our most seemingly outlandish thoughts void by deeming them irrelevant.

Follow the Daily Wildcat on Twitter