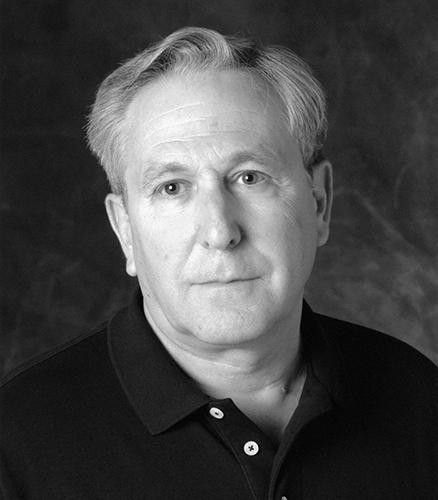

The UA professor and part-time local actor discovered, as an English literature professor at Purdue, how to use body language while pondering a thought or a student’s question in class.

“”I was in a production of (playwright Harold) Pinter’s ‘Old Times,'”” William Epstein recalls. “”He’s famous for all the pauses, and it will say it in the script — ‘pause,’ ‘long pause,’ ‘long, long pause,’ ‘silence’ — and you have to interpret all this sort of stuff.

“”But you can’t just pause. You have to act the pauses … If you don’t do it, the play doesn’t work. What you learn is that’s the way all theater works.””

Epstein has been teaching English literature at the UA for nearly 25 years. Yet he confesses to feeling more comfortable on a stage than being in front of a podium.

He recently played Eurydice’s father in “”Eurydice”” at downtown Tucson’s Beowulf Alley Theatre, and is doing a staged reading of “”Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”” at Live Theatre Workshop for his drama course at UA.

In an interview, Epstein starts, stops and backtracks as if he’s in a play or movie by one of his favorite playwright-directors, David Mamet.

How did you get into acting?

I was in first grade, my sister was in ninth grade, and it was a grammar school that went from kindergarten to ninth grade. The ninth graders got to put on the Christmas play, and they needed three little kids to ride across the stage on a bicycle route, ride across and run across next to them.

So I had no idea what the play was and I had no idea what the scene was about. All I know is (my physician’s sister) Adrian got to ride the tricycle and Ricky and I ran alongside it. And we just went diagonally across the stage and we got a laugh. And that hooked me — that did it. … You know, I thought that was the greatest thing in the world.

I’ve been doing theater ever since that, on and off, mostly off. Things would come up now and again. But life gets in the way, you know? Raising a family, get promoted and tenured, publishing — all this stuff gets in the way. So I didn’t do a great deal of theater until after my wife died.

When was that?

She died in late ’96 but this was probably two years later, in ’98. I’d been deeply grieving for a couple of years. … I was sort of out of things. It was four years of difficult times dealing with death in one way or another.

I went to see a play downtown at a theater, a place and a company that no longer exists called Quintessential (Productions), and they were doing a Noël Coward play. It was boiling hot. It was like in August and they didn’t have air conditioning, but the play was very good. They did it very good and I thought, “”I’d like to be a part of that,”” and I auditioned for them.

I got a couple of small roles in “”Taming of the Shrew”” that they were doing. … (I’m backstage and) suddenly, these two guys just start dancing to the swing music, not with each other, just sort of dancing to the swing music out in the dark hall. Nobody’s looking at us. And I found myself doing the same thing, too. It was this moment of glee, you know? Just pure glee, just joy. After having been in such grief, to be able to do just that, nobody’s watching, it seemed to me that’s also what the theater is about. Not always that theater is about going across the stage and getting a laugh, but it’s also about things that the audience never sees. It’s about part of the process. It’s about the moments of unadulterated pure joy that happen when you’re just there.

Are there any specific plays that you’ve performed that cover workplace drama?

Yeah, and this one is really relevant to what in fact you and I are sitting here doing right now: a play called “”Oleanna”” by David Mamet. I did it last winter at Live Theatre Workshop’s late-night series called Etcetera. It’s a two-character play and I play the older male professor and there’s a younger female student. It’s a play about higher education, about gender relations. It was originally written in the wake of the Anita Hill hearings so it’s about the perception of sexual harassment.

In fact, I’m teaching that play in my course this week. … The young woman (who played the student), Carley Preston, and I will be doing it for the class this Thursday.

Given that “”Oleanna”” is a two-character play, how do you approach that sort of work as opposed to other plays?

A lot of work. You literally have every other line. It was especially difficult because it’s Mamet. Mamet is very hard to act. You have to figure out how to do it. And I think we finally did, but it was very hard.

I found when I really got into theater intensely in the last dozen years or so, where I’m going literally from show to show to show, except for the summer, that it had a real effect on my teaching. I had not expected this at all.

When you’re the actor, you’re not in charge. The director is in charge and some other people also can be in charge. But you’re not in charge. I’m used to being in charge, right? I’m used to deciding on the curriculum, organizing the course, giving the exams and grading them, and leading the discussions. I’m used to being in charge in my academic work. But in the theater I’m not in charge. I’ve often been asked, “”Do you want to direct? Why don’t you direct?”” No, no, no, that puts me back in charge, that sounds like work again. And I really don’t want to be in charge, I want to be an actor. I don’t want to be the person in charge. …

But (acting) put me back in touch with what it’s like to not be in charge and what it’s like to really need the instruction and the preparation and being taught how to prepare. I think it changed my teaching. I think it put me back in. I watched what people did and it was really interesting to see how some of these people were doing things. …

The theater is humbling. (Laughs.) … I think I’ve learned how to be humbled again, and I think that’s an important lesson as teachers that we need to keep learning over and over again — and as people, too.

What were some of your favorite roles?

I was in a fairly well known comedy called “”I Hate Hamlet.”” It dates from the ‘80s or ‘90s, and I played (John) Barrymore in there. You get to swashbuckle with swords and pose in theatrical moments and clothing and stuff like that. For some reason, I don’t know what it was, when I did it I could do no wrong in that part, in that production. That doesn’t happen very often.

Even when things went disastrously wrong as it tended to do with this production — we had problems with the electrical service, some things were blowing out all the time — it didn’t matter what happened, I took it in stride and made something out of it. We’re in a swordfight and my sword gets stuck. I go back like this (raises arm behind head) and it gets stuck in a piece of Styrofoam. Even so, I could do no wrong.

This play had a magical moment. At the end of play, after the play was over, the actors would hurry around and we would get back to the front of the theater. As the audience left, we would shake their hands. It was a community theater and that’s the way they did things. It was a clever idea, connecting to your audience that way. And passing through the line is a friend who directed me in a play at another theater.

He says to me, “”How did you do that trick?””

I said, “”What trick?””

“”The one with the flower.””

“”What are you talking about?””

“”Where you threw the flower and it went into the vase.””

“”What are you talking about?”” Near the end of the play, for some reason I’m holding a flower in our production — in fact, it was an artificial flower. I walk from where I’m sitting on the side of the stage, upstage, to talk to the kid that I’m mentoring. And as I go, I throw the flower over my head and walk on. This particular night, it did a 360 and it went, stem first, back into the vase from which I took it. What are the chances of that, you know? (Laughs.)

He just assumed it happened every night and that we had some theatrical trick we do it.

“”Did you do it with string? How did you do it?””

I said, “”Chuck, that was just pure accident.””

He said, “”Wow, it was like magical. It was incredible.”” So I always had a fond feeling for that part.

I’ll tell you another story. This is one of my favorite plays because it’s a play from which I could tell a million stories. Here’s one of those stories. This was when I was at Cambridge on sabbatical and I was waiting to hear from a publisher whether they were going to give me an advance contract on a book. If they do, that’s the book I’m going to write; otherwise I’m going to write another book.

So I’m waiting and I take a part in a play. In Cambridge in the winter term, all the colleges have plays. It’s a quasi-big deal. I was associated with a college as a visiting scholar, but I didn’t want to do their play because I didn’t like it. Another college, Christ Church, they were doing Neil Simon’s “”Plaza Suite.”” You couldn’t think of a more American play. I was made to play Neil Simon. So I’m in the play with other people, the rest of them younger than I am.

We’re at the cast party after the run is over. One of the actors comes up to me. I was in the first act, he was in the second act. It’s “”Plaza Suite,”” see, it had all these different characters in different acts, but they’re all in the same room in the plaza. That’s the premise of it.

He said, “”There’s something I must tell you”” — I won’t do the accent — “”my mum came up to me and said, ‘The chap in the first act was quite good. His American accent was almost perfect.'”” (Laughs.) Isn’t that great? (Laughs) I remember that play because many, many things happened, including people getting knocked out onstage.

Oh, I know. I was in a production of Pinter’s “”Old Times.”” This was when I was at Purdue. With Pinter, he’s famous for all the pauses and it will say it in the script — pause, long pause, long, long pause, silence — and you have to interpret all this sort of stuff. You really have to do the pauses — the play doesn’t work unless you do the pauses — but you can’t just pause. You have to act the pauses. Well, you’re acting silence, you’re acting no language. If you don’t do it, the play doesn’t work. What you learn is that that’s the way all theater works. You have to act the silences, you have to act the pauses, and Pinter really teaches you that. It’s one of the things that contemporary theater does that’s different.

This is an appropriate time to use an overused word: Pinter’s plays deconstruct the way in which theatrical language is deployed, and they do it primarily through forcing you to act the pauses. As an audience, you have to follow that. You have to be intensely involved with the pauses, so that when they (the characters) come out of a pause and they say something, you know that it’s not what they’re thinking, but it is what they’re thinking. It’s coded and you know what it is code for. You don’t always know at first, but you learn the code as you go along. As an audience, you’re responding to those pauses and you’re working hard in those pauses to try to put together what’s going to happen next and what just happened. That’s fantastic. …

Then I would say I just recently did “”Oleanna”” by Mamet. Mamet is a kind of American Pinter, also experimenting a great deal with language, and with the pauses, and with the silences, and with the breakdowns. If you take a look at a Mamet script, it doesn’t look like other play scripts because it’s full of tiny little pieces of language, little bits and little starts. It can just be a letter with dots and then you get a little more, then you get a little of this word, then it gets repeated, and then this happens and that happens. It looks very strange on the page. You say to yourself, “”What the heck is going on?”” But if you learn how to act it, it comes out as the way people, in a sense, a highly stylized version of the way people really talk with all these stops and starts, they don’t quite get it right, they’re fiddling around, people often don’t get a chance to finish their sentences and they. Just like I did right there, right? That little bit. But for Mamet, that’s his meat and potatoes, that’s what the play is about. It’s about other things too, but it’s one of the things that the play is about.

That was a really wonderful experience for me, too. It’s very difficult. I, it, the opening monologue, my opening, I open the play. My character opens the play on the telephone for two pages, and it’s all bits and pieces, stops and starts. I have to convey to the audience what we’re talking about, and for a long time, you won’t be able to figure it out, but it’ll be fascinating anyway, if I do it right. I have to convey to you the kind of character I am, who I am and what I’m doing, and also tell you something about language. All this happens simultaneously and it’s a remarkable experience being the audience and to have this happen to you. But in order to convey it? Very, very difficult.

I started working on that speech the very first day I worked on the play. I was still working on it, still sweating over it, still trying to get it right. I worked on it every day, and I didn’t have a clue how to, I mean I had a, I knew what I was supposed to do and what I was supposed to get, but I didn’t know how to get there. I just kept working on it, and working on it and working on it, trying to figure out how to do that. It was very, very hard. I had seven phone calls, eight phone calls, something like that. Then I had a number of long speeches which are not the same sort of that, where I’m pontificating as a professor, a very different kind of mode (different voice). Much of the dialogue is overlapping, which is hard to time and hard to do. If you could do Mamet, you’ve really accomplished something, it seems to me. That was very hard work and very rewarding.