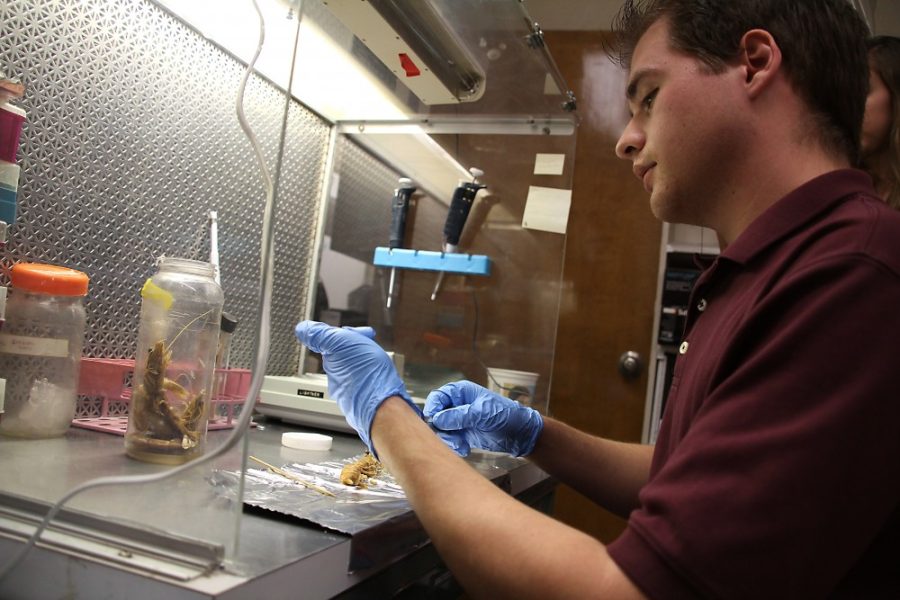

Nathaniel Vrana starts his shift at the UA’s Aquaculture Pathology Laboratory by opening a jar of shrimp that arrived in the mail the previous day.

The physiology senior puts on blue gloves and grabs a razor. He lays out one shrimp on a piece of tinfoil, quickly cuts off its pleopod, or fin, and puts it in a tube.

Vrana works part time in the diagnostic section of the lab and tests the shrimp for white spot syndrome, a contagious viral infection that can kill shrimp, and several other viruses. Shrimp farms and other companies from around the world send in samples of potentially unhealthy products, including fish eggs, lobsters and blood worms, to the UA’s lab and pay for a diagnosis.

Every day after class, it’s Vrana’s job to remove parts of the creatures for DNA and RNA extraction and run the diagnostic tests.

“This part is interesting, with the diagnostics,” he says. “It’s all shrimp but it can be applied to other situations.”

Vrana, who is applying to medical school, spent nearly a year working in a laboratory in the Arizona Cancer Center. He then heard about an opening in the aquaculture pathology lab and has worked there for the past few months.

The lab, located in the Veterinary Science and Microbiology building, is one of the only in the world to offer these diagnostic services — so companies from countries such as Belgium, Germany and various others in South America send their samples to Tucson, Vrana says. Aquatic creatures normally come frozen or preserved in an ethanol solution, he says as he opens a freezer full of the lobsters, shrimp and squid the lab had previously diagnosed.

The lab receives shrimp most frequently, Vrana says, which is good because they’re easy to test.

“The blood worms are a mess,” Vrana says. “You open those things up and it’s almost just like liquid.”

Vrana begins the diagnostic process by removing part of the creature and putting it in a test tube. The sample is then run through a polymerase chain reaction, or PCR test, to extract its DNA and RNA.

He walks downstairs to another laboratory and diagnoses the virus using a gel electrophoresis test. The DNA is put in a well and compared to samples of the virus, water and another tissue sample.

A current is run through the well. Bands appear in the samples, and the location of the band identifies the virus, Vrana says.

“It’s kind of obvious,” he says, adding that the graduate student he works with writes a diagnosis report to send to the company.

Companies can pay an extra fee to have the process completed in a day, Vrana says. Otherwise, he just works until “there’s nothing left to do,” which means his hours vary depending on how many packages the lab receives.

Vrana also maintains the lab for the other research going on — he takes out the trash and makes buffer solutions. But testing is his favorite part, he says.

“Really I like the diagnostic part,” Vrana says. “It’s similar to what I was doing in the cancer center.”

And because the lab is run like a business, he is usually busy, Vrana says. He’s become quicker in the testing since he started the job.

And unlike his work at the cancer center, when experiments were always changing, the work in the pathology lab is fairly routine, Vrana says.

“Now I can get through a couple of cases in a couple of hours,” he says. “It gives me more comfort doing the same thing over and over.”