Two architecture seniors are one step closer to building their dreams through their capstone projects.

Senior capstones aim to showcase the knowledge a student gained during their time in college. Brandon McBrien, a senior who studied architecture, regional development, and business management, said he managed the stress of completing his capstone project by always keeping his ambitions in mind.

“I want to align myself with a firm that bridges the gap between profit and non-profit projects,” McBrien said. As someone who wants to do pro-bono architecture work, his business background will allow him to see which projects would make the greatest difference at the lowest cost, he said.

McBrien’s regional development thesis argues that a manmade environment has the ability to build a set of values for its culture, while his business capstone is an investigation of the Tucson architecture firm Neptune Thomas Davis.

McBrien proposed different strategies the firm could use to overcome corporate challenges and first began his research in the fall when he met with many of the firm’s employees.

“Regional development and business management give me an idea of how my architecture clients might be in the future,” said McBrien, who came up with a “gain-sharing mechanism” for the firm to distribute its profits to employees based on individual performance. He also suggested that the firm use more social media to advertise its environmentally conscious and communal efforts.

After presenting the information he collected to a panel of faculty in the Eller College of Management, McBrien said he has a better understanding of the emerging marketing trends and economic ideals necessary for running a successful business.

“Architects are notorious for being bad business people,” he added.

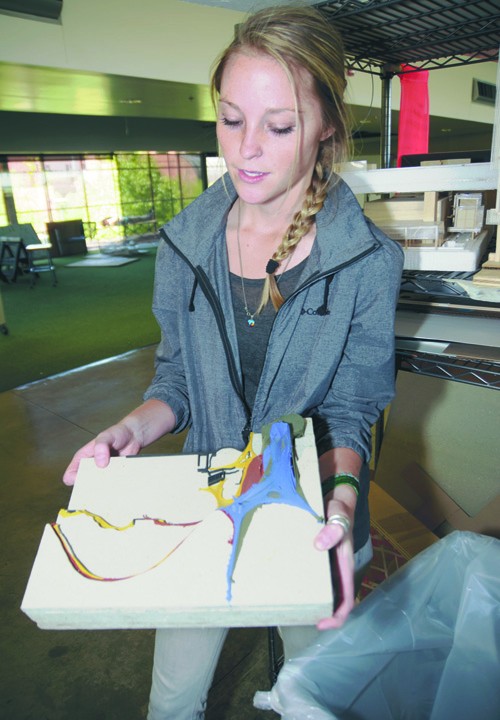

Architecture senior Laura Huylebroeck has spent more than 100 hours completing her capstone project in time for portfolio reviews. Her project is a remodeling of the Sutro Baths ruins in the San Francisco bay. Her project integrates the history of the remains with a research facility that would allow people to study the wetlands that are emerging over the ruins.

“The ruins have always intrigued me since I was a little girl,” Huylebroeck said, “and I’ve always wondered what could be a good addition to them.”

She built six models from various materials like Styrofoam and medium-density fiberboard to display the multiple layers and visual perspectives of what she envisions the research facility to look like amid the ruins. The integration of the past with the present through architecture has always been an alluring idea, Huylebroeck said.

“I want people to keep the past in mind, but to also see what has developed now,” Huylebroeck said. “And to see how the two can talk to each other.”

The six models, along with mulitple drawings and research material, were assessed during an eight-minute presentation followed by a 15-minute discussion with faculty members from the College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture.

As someone whose past projects include modern libraries and the reconstruction of a theater building in Tucson, Huylebroeck said her architectural education gave her the variability of a “Renaissance man.”

“I have become a much more well-rounded person with the knowledge I’ve soaked up,” she added.