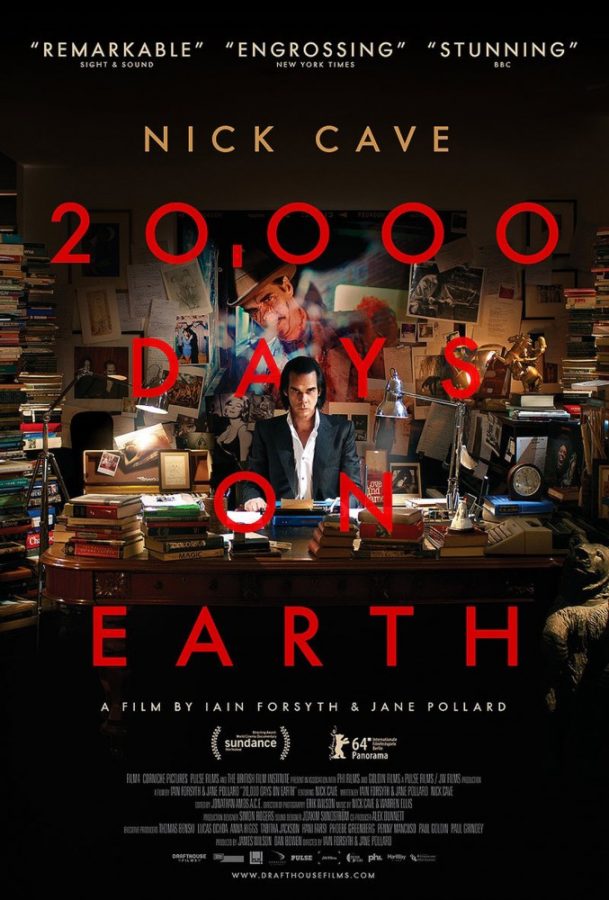

“20,000 Days on Earth” is a film exploding with creative bravura.

Part documentary, part hyper-realist construct, the film is a perfectly pieced pastiche of rock poet Nick Cave’s existence. Released in the U.S. on Oct. 17, British directors Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard deftly paint a portrait of an artist through cinematic techniques different to that of the “fly on the wall” style reminiscent of day-in-the-life documentaries.

The most admirable aspect of the film is the way the pragmatics of documentary making are discarded for cinematic truth. The audience is treated to a heightened and fully-realized version of events that is, in some ways, clearer than a typical interview. This echoes the thematic line the film often refers to: Through creativity, we can change who we are, and we can transform into something different or someone greater.

In the opening scene, Cave announces it is his 20,000th day on Earth. He has, by his own ostentatious account, “ceased to be a human being.” Seemingly pretentious and esoteric, these literary quips continue throughout the film. However, through intimate and gently handled interviews, Cave’s humanity shines through the cracks of the persona he has created for himself. His voice resonates over scenes like an all-encompassing deity, creating a coherency between interviews and performance footage.

Over the course of the next hour and-a-half the audience is treated to a Jim Jarmusch-like account of Cave’s daily interactions and recording processes. The film is essentially an account of the artist and his band, the Bad Seeds, releasing a new album.

Stylistically, “20,000 Days on Earth” is beautiful to experience. Ornate frames flow from one to another. Artistic renderings of Brighton, England, establish the city as an important factor in the carefully scripted documentary. Spliced with the establishing shots are past concert recordings which run at breakneck speed. These images are backed by an exquisitely crafted soundscape gently floating at times, yet trembling with monolithic grandeur at other points. The dichotomies within the sound and sights of the film work because they contribute to the themes Cave muses over. When artifice and realism intersect, they create something new and transcendent of classical form.

Though “20,000 Days on Earth” is an account of an artist not widely recognized in the U.S., both fanatics and newcomers to Cave’s body of work will enjoy the film. At times, the directors border on being overzealous but always wrangle the film back when it becomes too much. As a film that delivers both an emotional response and a technical feast, “20,000 Days on Earth” is one of the greatest documentaries of 2014, perhaps even the decade.

Through a dialectic between imagination and authenticity, the film breaks new ground in cinema. The lilting cadence of Cave reinforces this in the lyrics of the film’s closing song, “I’m Transforming, I’m Flying, Look at me now.”

_______________

Liam Lowth is a guest reporter. Follow him on Twitter.