In 1971, NASA’s Mariner 9 entered orbit around the planet Mars, becoming the first spacecraft to ever successfully orbit another planet. By the end of its mission in 1972, the orbiter mapped 70 percent of the planet’s surface, transmitting more than 7,300 monumental images that transformed the realm of science.

Some of the detailed images Mariner 9 captured were of the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos, Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system and Valles Marineris—a canyon system several times larger and deeper than the Grand Canyon.

At the time, Victor Baker had been an environmental geologist at the University of Texas.

RELATED: UA’s Green Career Mixer ‘suc-seed-ed’

Baker had always floated from specialty to specialty, never truly knowing what kind of geologist he wanted to be. However when NASA released the vivid images of the red planet’s surface, Baker envisioned discovery.

“[Those images] were so incredible that they changed one of the orientations of my career,” Baker said. “I became instantly interested in how water processes had affected the surface of Mars.”

Since the deep channels on Mars could only have been formed by water, the images suggested the current or past presence of life.

The images fueled the slow-growing field of astrobiology—then called exobiology—which had its first NASA-funded project only 12 years prior, in 1959.

“Life as we know it, at least as we know from Earth, is intimately and always essentially associated with water in some kind of way,” Baker said. “So, naturally, that leads me to be interested in life because it is intimately connected to the water processes.”

In 1975, NASA sent the Viking 1 lander to the Martian surface, to search for signs of microbial life. Their small exobiology program grew and in 2000, the first Astrobiology Science Conference was held. The field was booming.

Baker found himself immersed in the field of astrobiology, where he used his background in geomorphology, the study of the physical features of Earth’s surface and how they relate to geological structures, and paleohydrology, the study of how water sculpts land, to determine how water formed the surface of Mars and if life forms participated in the transformation.

RELATED: Campus-run organizations help provide ‘food assistance’ to UA community

Now, Baker is a Regents’ Professor of hydrology and atmospheric sciences, geosciences and planetary sciences at the University of Arizona, where he plays an integral part in the astrobiology program.

The UA offers a pioneering astrobiology minor and is one of only five universities in the U.S. to have an undergraduate astrobiology program at all, according to NASA.

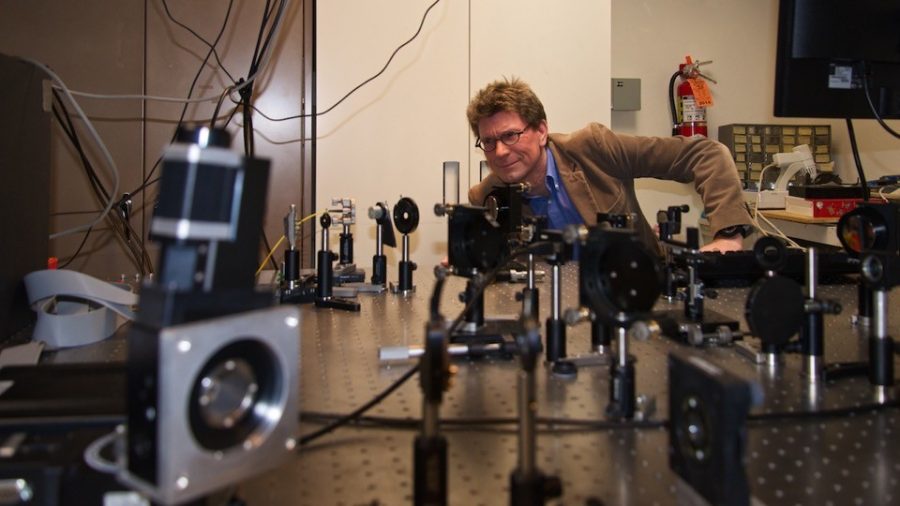

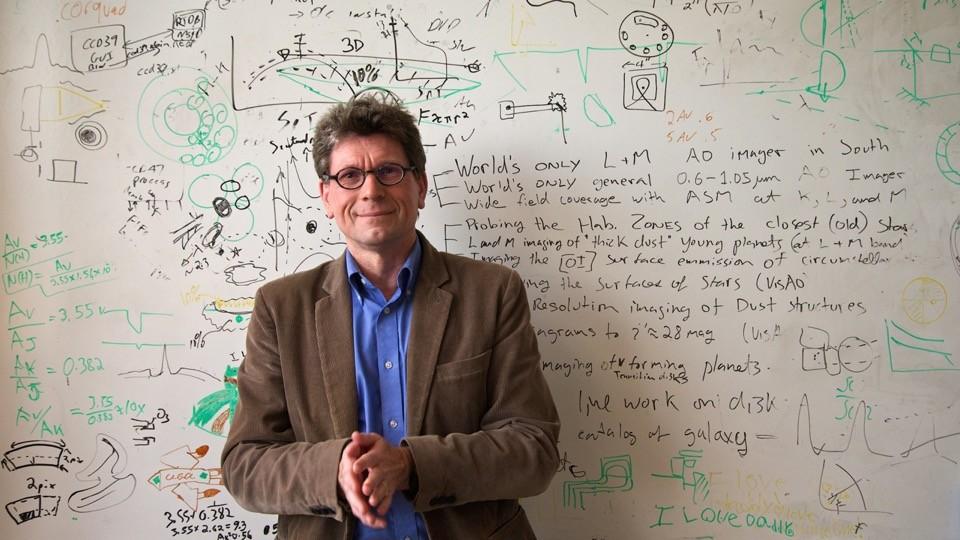

Despite this rapid advancement and growing excitement within the field, astrobiology remains a smaller field due to its interdisciplinary nature and it is not an “obvious” minor to undertake, according to Laird Close—professor and adviser for the undergraduate astrobiology minor at the UA.

“It’s common, if you’re majoring in, say, physics, to have a minor in astronomy,” Close said. “But astrobiology as a minor doesn’t naturally pair with anything. It’s not at all obvious.”

It also does not function well when taken simply because of an interest. According to Close, minoring in astrobiology is not advisable for students not majoring in the sciences—though he does teach Astronomy 202 in the spring — an introductory level, tier two elective course designed for non-science students who are interested in the subject.

“[Astrobiology] is a bit esoteric,” Close said.

Astrobiology is an interdisciplinary subject that requires in-depth expertise in a broad range of sciences including chemistry, astronomy, physics, geosciences, biology and more.

Universities generally have a difficult time with such broad program. However, the UA is unique in this regard.

Unlike most universities the UA has departments of hydrology and planetary sciences. Such specialty science programs are usually embedded in other basic science departments, according to Baker.

Most universities do not have such grand, innovative programs as the UA either, according to Close.

RELATED: Migration, the media and militarization

The UA is actively partnered with NASA and other universities in many ongoing projects, including the construction of the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) in the Atacama desert—a 368 square meter telescope 10 times stronger than the Hubble telescope. It is scheduled to be completed by 2025 and is made possible by the nation’s top universities, including UA’s Mirror Laboratory.

“They need us,” Close said. “Harvard and MIT [who are also partnered in GMT] wouldn’t know how to build something like that, so they come to the UA because we are the world’s best at building large telescope mirrors.”

These multitudinous departments and research opportunities make the UA a petri dish for science itself. As Baker said, it was only natural that the UA took on the challenge of promoting astrobiology at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

“The UA is a very exciting place to be at, that’s why I ultimately came to Arizona so many years ago. I just felt it would be a place that would develop in this exciting way and it has,” Baker said. “I don’t think I made a mistake coming here.”

“We have no evidence that life exists anywhere else,” Close said. “However, we believe there are billions of Earth-like planets just in our Milky Way galaxy. And if there are so many, many of them likely have life on them because life works so well here on Earth.”

As of now, astrobiology technology is still being developed, so astrobiologists are limited to far off observations of biosignatures from exoplanets and information gathered from terrestrial life.

“This is a really rich field that is about to take off. It’s going to be one of the most exciting fields in science,” Close said. “[Astrobiology is] a very fertile area for research because we don’t understand very much about it. We don’t really understand the origins of life. We can’t even create life in a test tube, we don’t even understand simple life. Our ignorance on this topic is significant.”

According to Close, while there is no definitive or groundbreaking knowledge of Earth’s biogenesis, life on Earth as it is currently understood, developed independently from other exoplanets.

“We only know of life here on Earth. We only have one data point and all terrestrial life is, in a way, identical,” Close said. “We only have one example in one spec of the universe.”

This makes theorizing about extraterrestrial lifeforms difficult. If life developed on other planets, it is likely very, very different from what we see here on Earth.

“It might not even use liquid water as a solvent. It might use liquid methane. The whole chemistry could be completely different, let alone it would look very different,” Close said. “We probably don’t have imaginations that are good enough to imagine the multitude of different possibilities.”

Yet, according to Baker, astrobiology is an exceedingly important field of study because of how little is known and because there is “potential for fantastic, earth-shattering, transformational discoveries to be made”.

“Finding an Earth-like planet around a Sun-like star and finding life on that world—that would change everything,” Close said. “‘Are we alone?’ These are questions people have asked themselves all through time, but now, people today are going to walk this journey to discover life on other worlds.”

Follow Daily Wildcat on Twitter