Researchers at the UA recently discovered that the venom of the brown recluse spider has a different effect on the body than previously thought.

Their findings, published in the online journal PLOS ONE, could lead to the development of better treatment for the spider’s bite, which can be fatal.

“This is something that happens fairly often in science,” said Matthew Cordes, associate professor in the department of chemistry and biochemistry, “which is that you start out trying to answer one question and you wind up finding something you didn’t expect to see and answering a different question.”

The researchers in Cordes’ lab orginally developed an experiment to compare the effects of spider venom toxins on different molecules within cell membranes. What they found was that the toxins produced by a family of spiders generally referred to as brown spiders were showing effects entirely different than expected, he said.

Brown recluse spiders, also known as violin spidersbecause of the markings on their head and back, can be found primarily in North and South America, with several species here in Arizona.

In the rare event that a brown recluse spider bites a human and venom is injected, one of two things happens. The most common effect is that the venom soaks into the skin and damages the cells, causing the development of a painful lesion in the affected area, said Dr. Leslie Boyer, founding director of the Venom Immunochemistry, Pharmacology and Emergency Response (VIPER) Institute.

In a small number of cases, a reaction occurs throughout the body that can lead to death by kidney failure and other causes, Cordes said.

Those are the easily observable, large-scale effects. At the molecular level, though, things are less than clear.

“What happens when venom gets into the skin has always been something of a mystery,” Boyer said, “and the work that was published [two weeks ago] is a major step towards understanding what goes on in the tissue.”

For their study, the researchers focused on phospholipids, which are the molecules that make up the membranes of cells, said Cordes, adding that if phospholipids are damaged, they can cause the cell to lose its integrity.

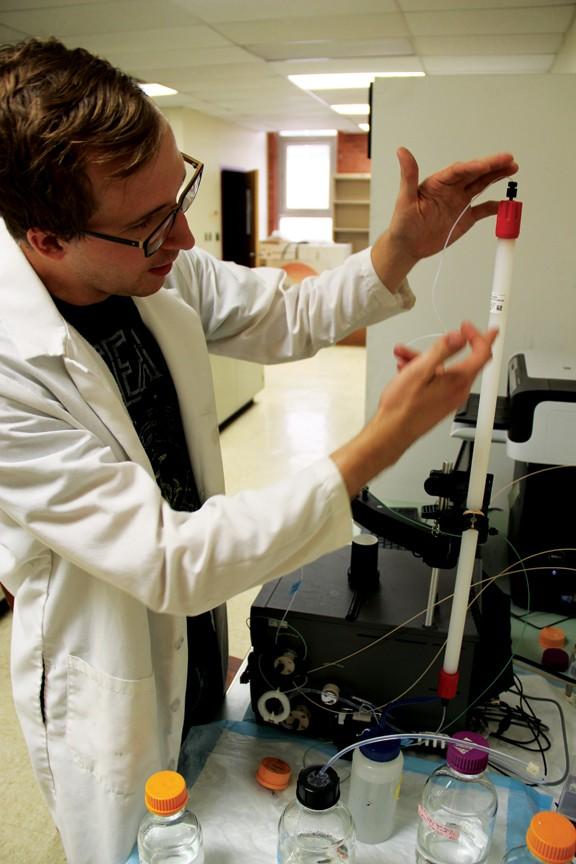

Through the use of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, a technique employed to determine the properties of organic molecules, the researchers were able to examine exactly how the brown recluse spider venom was affecting the phospholipids, said Daniel Lajoie, a graduate student in the department of chemistry and biochemistry and the first author of the paper.

Instead of merely knocking the “head” off of the phospholipid molecule, which is the effect researchers previously attributed to the toxin, the team discovered that the head of the molecule is actually replaced by a significantly different ring-shaped structure, according to Cordes.

Although the findings shed new light on the chemistry involved, the downstream effects the toxin has on the body are still something of a mystery.

“We hope that other researchers will now take these results, and that it will inspire them to do experiments to help untangle all the effects that happen after the initial action of the toxin,” he said.

Vahe Bandarian, an associate professor in the department of chemistry and biochemistry and co-author of the paper, said that the findings could eventually lead to better treatment options for bite victims.

“If you could understand how that one system works, you might be able to find a way to inhibit it,” he said.

Despite the dangers that brown recluse spiders present, Lajoie said that the arachnids spark his curiosity.

“[Considering] what they can tell us and the secrets that they have, there’s lots and lots of research that needs to be done into what spiders can produce,” he said.