Motivated to help local couples and enticed by money, college women around the nation are becoming egg donors to satiate the increase in demand, despite ethical, social and physical implications.

About 60 of the 75 egg donors at both of Tucson’s infertility clinics come from the UA, Pima Community College and other neighboring colleges each year, according to the local clinics.

Sarah, a 22-year-old veterinary science junior whose name has been changed to prevent identification by her egg’s recipient couples, donated her eggs three times in the past year.

The increase in demand for egg donors results from women having children later in life and the higher remarriage rate. Some couples have elective sterilization from a previous relationship, which cannot be reversed and leaves in-vitro fertilization as their only option, said Holly Hutchison, co-owner of the Reproductive Health Center in Tucson.

Egg donors between the ages of 21 and 30 are sought because eggs decrease in quality as women get older. Women have a set number of eggs from birth, and everything they are exposed to in their lives their eggs are exposed to as well, which decreases their quality, said Long Huynh, a third-year medical student who is doing a rotation at the Reproductive Health Center.

In search of healthy eggs, “”Donate Now”” advertisements offering up to $10,000 for eggs are common sights on bulletin boards online, Craigslist.com and in college newspapers across the nation.

Reproduction Solutions, an agency out of Los Angeles that connects recipients with a desired donor, offered $5,000 to donors in daily advertisements in the Arizona Daily Wildcat last year.

One of Tucson’s two infertility clinics, the Arizona Center for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, also advertised with the Wildcat in hopes of recruiting donors, according to Dr. Timothy Gelety, director of the center.

“”A lot (of agencies) advertise you can make X amount of dollars and that has cut a lot of interest in our program, because some people call us and say that we don’t pay enough,”” said Gelety, whose clinic offered $1,000 to $2,000 for first-time donors.

The Reproductive Health Center, another Tucson clinic, offers $3,500 for each donation to compensate donors for their time and trouble.

The money the majority of women earn is used for school, Hutchison said.

“”Although not the primary reason for donating, the monetary compensation was enticing because I do need help for school and it is hard to get financial aid,”” said Sarah, who received $3,500 for one donation and $3,000 for the other two. “”I have to pay for school myself. I don’t have much help for that, so that is basically where most of it went.””

Motives for donation

With eggs fetching thousands of dollars, the donation market, which lacks rules regarding compensation limits, is often criticized for turning eggs into commodities. But, for many, this lightly-regulated industry is more than a market for transactions.

Some women donate to help others.

“”I thought it was a neat thing to be able to do, to help somebody out because basically for a lot of these people, it is their last resort and they have gone through enough,”” Sarah said.

Kieran Healy, an assistant professor of sociology who has written a book on the blood and organ donation industry, said, “”Not all transactions that happen for money only happen for money. There is a very strong gift element to these exchanges and those gift elements don’t go away even when there is money involved.””

One UA alumna and Tucson resident said she became a donor to help a family member who had exhausted all resources and endured a failed adoption attempt.

“”I was 33, my stepmom was 48 and her eggs were too old, so I said, ‘What do I have to do?’ and in five minutes, I decided,”” the UA alumna said.

“”I donated out of love.””

Egg donation process

1. The potential donor undergoes physical, genetic, and psychological screening prior to the donating process.

2. Once chosen by a recipient couple, the donor begins hormone replacement therapy to suppress the menstrual cycle.

3. The donor then begins ovarian stimulation medication to increase the number of eggs that will develop. The donor self-injects this medication daily.

4. Ultrasound monitors the growth of the eggs while blood and urine samples are taken to measure the hormone levels.

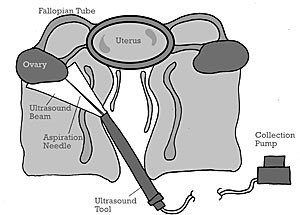

5. Once the eggs are at the proper stage, they are extracted by a

process called follicular aspiration which is non-invasive and performed under mild sedation and local anesthesia.

6. The eggs are then placed with the man’s sperm within hours of extraction to be fertilized. The fertilized egg begins to grow and divide into an embryo, which is then placed into the recipient.

-Compiled by Courtney E. Smith

Designer babies

With stories of models being actively recruited to donate their eggs, many people fear egg donation technology will result in the creation of “”designer babies.””

But the majority of donors do not spend their time on the runway; they spend it in the classroom.

“”The majority of donors have some level of college education,”” Hutchison said.

“”We don’t see a lot of people who are just looking for people who look like models,”” Gelety said. “”Couples are really interested in educational achievement. Some people want to know the SAT scores, some are really interested in the appearance.””

But in the end, couples want a baby who is like them, looking for a donor with similar ethnicity, hair and eye color, and weight characteristics to match the recipient woman, Hutchison said.

“”I was told I have pretty classic features so I would probably get picked easy, because I guess I blend into families pretty easy,”” said Sarah, who is white.

Reactions from people

Although egg donations increased 12 percent from 1996 to 2004, according to the most recent data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the idea of donating eggs still elicits mixed reactions.

Some people are OK with it. Others are curious, and some think it is just weird, Sarah said.

Many women avoid donating eggs because they have reservations about their eggs becoming someone else’s child.

“”I don’t really think about that because it’s partly my DNA, it is part of me, but it’s not really my child,”” Sarah said. “”It has its parents that are going to raise it.””

Even though the process is usually mutually anonymous, Sarah exchanged a few letters with the couple. They said she could meet them, receive pictures or even meet the child if she wanted.

“”They wanted to let the child know that I was a part of its life, which is neat, but I don’t know if I’ll ever actually meet the child … I don’t think I’ll ever seek that out myself, but I’d be open to it,”” Sarah said.

“”They sent me flowers when they heard the heartbeat,”” she said. “”For me, it was just so rewarding that it doesn’t even bother me.””

Although Sarah said she will always wonder about the child, she doesn’t worry about it.

But the UA alumna who donated her eggs disagrees. If she didn’t know where the child was, “”it would be kind of weird,”” she said.

Donating not easy

“”Becoming a donor isn’t easy,”” said Dr. Scott Hutchison, founder of the Reproductive Health Center, the clinical assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the UA College of Medicine and director of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. “”It isn’t like giving blood.””

The six to eight week process involves intensive screening, nightly injections of hormones and, ultimately, having a minor surgical procedure to remove the eggs.

“”It gets to be a lot. I work part time and go to school full time, and it became really hard,”” said Sarah, who said the time demand of the donating process is part of the reason her third donation will be her last.

Egg donation, like most medical procedures, has its risks, including pelvic bloating and tenderness, breast tenderness and in extreme cases, hyper-stimulation of the ovaries.

“”It was rather rough,”” the UA alumna said. “”You have to go off birth control for a whole month. You can’t have sex. If you become pregnant, you can cause yourself horrible physical harm. Most women end up producing about 10 eggs, I ended up producing 40 eggs.””

When the eggs were aspirated, fluid filled the space and it was incredibly painful, the UA alumna said.

“”For about five days, I was laid up after they took the eggs out of me,”” she said. “”I couldn’t move. I was in agony.””

But for others, the physical process is painless.

“”It was pretty easy for me. I carried it all pretty well,”” Sarah said.

While not for every woman, egg donations are relied on by couples that often have no other options to start a family.

“”After you try and try, and all this time goes by with no success, we were willing to try IVF (in-vitro fertilization),”” said a Tucson woman, who successfully had children with her husband through the help of an egg donor.

Sarah said while egg donation is not for everybody, if a woman is interested, she should research the procedure and make sure it is something she wants to do.

“”It is a great experience for someone who wants to do it,”” Sarah said. “”Without people like me, they wouldn’t be able to have children.””