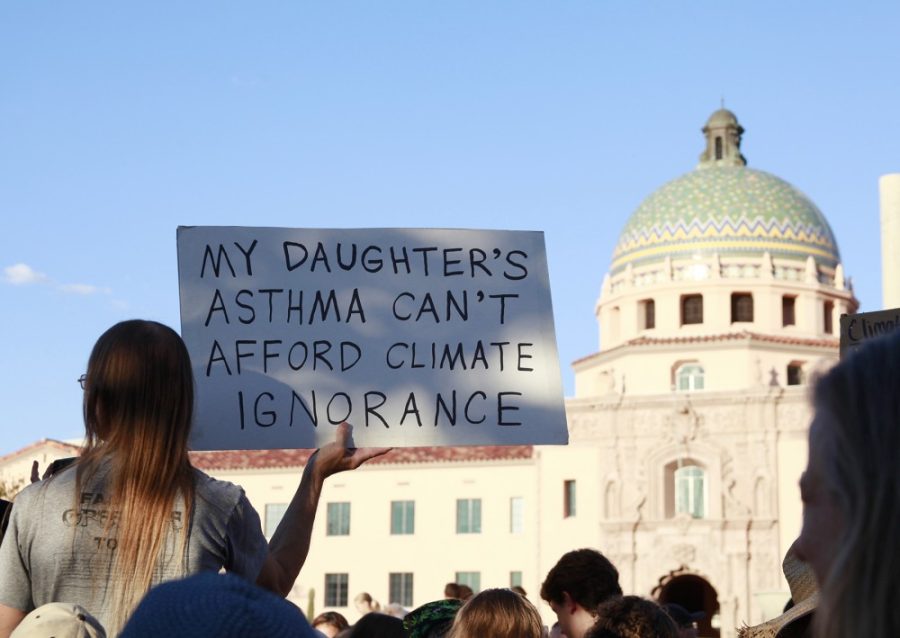

As University of Arizona junior and climate activist Kyle Kline chanted among several hundred concerned Tucsonans at a September 2019 climate strike, his hope was that city officials would solidify their commitments to climate action.

“The main asks for the strike were the climate emergency declaration and the climate action plans,” Kline said.

During the following year, Kline dedicated his time away from classes to gathering signatures, planning another climate strike and advocating alongside environmental organizations with the hopes of proving to city administration that this is what members of the community want.

About a year after the climate strike, Kline’s prayers were answered, as Mayor Regina Romero and her city council declared a climate emergency, preceding a plan to make Tucson carbon neutral within the next decade.

Tucson is one of 1,863 jurisdictions across the globe that have declared a climate emergency since 2016.

Climate emergency declarations act as acknowledgements of the catastrophic effects anthropogenic climate change is inflicting on humans and the environment. They also tend to represent vows that local governments will take to contribute to global climate efforts.

Tucson is the third-fastest warming city in the U.S., so climate is a leading priority for Romero and her council.

“We broke records in terms of heat. We broke records in terms of days over 100 degrees. We did not see a rainy season. We did not see a monsoon this year. We saw the Bighorn Fire burn thousands of acres in the [Santa] Catalina Mountains,” Romero said. “We are seeing the effects of climate change in front of us and so we’ve got to act boldly and swiftly because we want to make sure we have a livable city.”

Romero outlined some ways in which she and the Tucson City Council are seeing their climate action plan to fruition.

The first step is to brainstorm. This involves meeting with city departments and identifying short term and long term strategies to green their areas of responsibility.

Some of these sustainable strategies across Tucson’s departments and utilities include fully eliminating waste by 2050, electrifying public transit and switching to renewable energy for electricity generation.

Tucson Electric Power, which has a long history of coal-powered electricity generation, has already jumpstarted their transition to an 80% reduction in carbon emissions by 2035.

Brainstorming has also included gathering ideas from other Arizona cities like Flagstaff, which declared a climate emergency in June.

Another area of Romero’s plan includes her “Million Trees” initiative.

Through partnering with local organizations like Trees for Tucson, Romero said she wants to expand Tucson’s canopy by planting 1 million trees by 2030. This not only enhances the area’s ability to sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but it also increases quality of life, Romero explained.

“People love trees,” Romero said. “Trees make a physical, psychological difference in people.”

The City of Tucson recently hired Nicole Gillett, formerly a conservation advocate for the Tucson Audubon Society, to act as an urban forestry manager for this undertaking.

One major aspect that the Million Trees initiative partners look to take into account, is improving climate conditions among low-income communities and communities of color.

Kline, whose efforts as the cofounder of the Arizona Youth Climate Coalition have given him a strong voice in the city’s environmental operations, said that this focus on vulnerable populations must be a core tenet of Tucson’s climate planning.

“Everybody’s really big push is to make sure that it’s done in socially equitable ways so that it benefits marginalized communities,” Kline said.

According to Margaret Wilder, a UA professor of geography and Latin American studies, greater vulnerability to extreme heat is a result of the resources a community has to cope, which leaves low-income populations in Tucson at a higher risk.

One example of this is that low-income houses sometimes have more difficulty with cooling systems in the summer, which could exacerbate financial or medical hardships. Wilder believes that a solution is creating a mindset in which air conditioning is not a luxury but a human right.

Tucson, one of the poorest large cities in the U.S., is not only at the forefront of the changing climate’s environmental consequences like drought and heat waves, it is also at the forefront of climate justice topics like disproportionate exposure to extreme weather.

UA “climate gap” research suggests that income, immigration status, age, race, ethnicity and gender are all factors in the disproportionate burden of climate risks in the southwest.

Wilder explained that climate change in Tucson cannot just be looked at as an environmental issue, but it must also be seen as a justice issue with underlying economic and cultural contexts.

“The whole issue of climate justice is really one of equity that we need to be looking at,” Wilder said. “We see it over and over again, we see the way the pandemic has disproportionately affected communities of color or low-income, we’ve seen it with public health and now we’re seeing it with extreme heat as well.”

Romero stressed that going forward, public input matters in this reach toward climate change mitigation and climate justice.

“Sending in an email or calling in to mayor and council meetings just to indicate support, calling their state legislature, their governor, their congressperson to say, ‘please support investment in climate action,’” Romero explained, “these are all individual steps that people can take in which their voice matters and their actions matter.”

Follow the Daily Wildcat on Twitter