Amidst the flags adorning the UA Mall and the names of Holocaust victims being read throughout yesterday and early this morning, some may have heard the pleas of people hoping to bring an end to yet another genocide as well.

“”After coming out to the vigil after my freshman year I thought, ‘Wow, this is really cool what we’re doing here,'”” said Erica Soloman, president of Students Taking Action Now: Darfur. “”But it fails to be relevant if we do not acknowledge the genocide occurring today.””

The 16th annual, 24-hour Holocaust vigil, put on by the Hillel Foundation, did more than to make sure that history is not forgotten – it brought hope that genocide has the potential to be stopped.

Many students attended the annual vigil, which featured a museum and children’s memorial, frequent speakers who survived the Holocaust and genocide refugees and free screenings of films meant to educate others on the atrocities. Only in the past couple years has the vigil taken a more global approach, said Michelle Blumenberg, executive director of the Hillel Foundation.

That global approach focused on the conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which erupted in early 2003, when the Sudanese government released the Janjaweed, an Arab militia, against its own people. The Janjaweed continue to kill civilians, rape women and young girls and destroy sources of food.

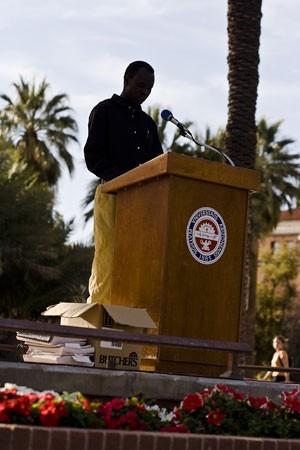

Wendy Theodore, assistant professor of Africana studies, spoke yesterday morning, asking the community when they will step up and help end the genocide.

“”There is no magical number that we should be waiting around for before we can deem mass murder as genocide,”” she said. “”The numbers are 400,000 killed, 1 million people in refugee camps and 3.5 million displaced.””

An hour of the vigil was devoted to a few of the Lost Boys of Sudan, who spoke about their experiences in Darfur and shared what they are doing to stop it and how others can help.

Lost Boys of Sudan is the name given to more than 27,000 boys who were displaced due to the violence in Darfur. In 2001, about 3,800 Lost Boys arrived in the United States, according to the Alliance for The Lost Boys of Sudan Web site.

“”Watching your village burn and your brothers die and burying them with your own hands are images that torment our minds here in America,”” said Abraham Ater, who graduated from the UA in 2006 with a physiology degree and is one of the Lost Boys. “”There is only depression daily and there is potential mind loss in the Lost Boys community.””

Ater said he and others face a financial burden as they attempt to send money back home to Darfur and make money for their own living at the same time. Some have stopped going to school because they don’t have enough money left over after sending it back to their families.

Ater recently returned to Darfur with a friend and founded a non-profit organization called Lost Boys Schools for Sudan, which is in the process of building three schools in the region.

“”Being there was very difficult. We saw the needs people are looking for. They need healthcare, food, clothes and education,”” he said.

Those who met with the Lost Boys after the meeting asked themselves why after all these years nothing seems to have been done to solve the conflict in Darfur. Soloman turned to a Holocaust survivor and asked if people behaved the same way when confronted with the murder of millions of Jews in Germany.

“”When it was started and when it was happening no one gave a damn,”” said Lily Brull, a refugee of the Holocaust who was born in Belgium. “”And if someone would’ve given a damn, there wouldn’t be 6 million dead.””