“As a pretty young kid who was moving around a lot, focusing on reading, writing and history didn’t seem worth it. I had to relearn it all in a new language every time, but math is the same everywhere. Math was the only thing worthwhile to learn,” said Lia Medeiros, a graduate astrophysics researcher at the UA, reflecting on her childhood.

Medeiros, originally from Brazil, settled in the United States after her 10th birthday. Her childhood devotion to math followed her through high school where, in a physics course, she first encountered black holes.

“Black holes were my love. I remember going to my physics teacher and saying, ‘I want to study this,’” Medeiros said. “I realized the entire universe could be described in math.”

After graduating with a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of California, Berkeley, Medeiros began her doctoral studies at the University of California, Santa Barbra, with a National Science Foundation fellowship before her research brought her to the UA, then to Harvard, then back to Tucson. Her math, like before, traveled well.

RELATED: New associate Vice President of Tech Parks Arizona is Bringing the Storm

The research of married team Feryal Ozel and Dimitrios Psaltis, both professors of astronomy at the UA, brought Medeiros to Tucson, where she will soon defend her thesis and earn her doctoral degree.

Medeiros’ research has focused on using black holes to study the fundamentals of physics, specifically gravity.

“The event horizon of a black hole is the mathematical boundary between the inside of the black hole, where nothing, not even light, can escape, and the rest of the universe,” Medeiros said.

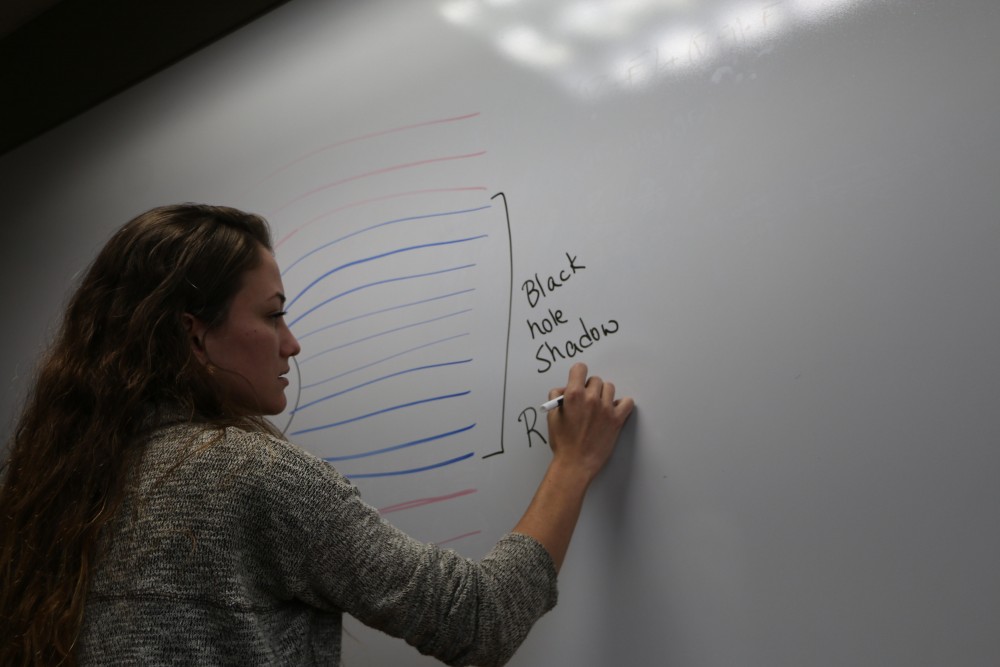

Black holes and their event horizons cast an observable shadow on their surroundings, which include the gasses and other objects falling into their abyss. Medeiros’ project has focused on building a mathematical model to describe the geometry of these shadows.

For Medeiros, this involves a lot of math, computing power and time spent in her office.

According to models built from Albert Einstein’s famous theories on relativity and gravity, the size and shape of a black hole’s shadow should be determined mostly by its mass and a little by its spin.

Yet these Einsteinian models explaining gravity and the universe are not the only models out there.

Medeiros said she thinks studying black hole shadows offers a path toward showing one of these theories is better than the rest.

“It is one thing to say an observed black hole is not what we expect to see. It is another to say what this shape means,” Medeiros said.

This is the essential problem that has faced scientists up to this point in using black holes to test these theories: No one really knows what black hole shadows should look like according to these other theories.

RELATED: Dogs and DNA: study lead UA researcher finds canine personality traits linked to their genes

Medeiros thinks she has found a solution to this problem.

By simulating over 12,000 unique black holes using computer simulations, some of which have metrics based on Einstein’s theory and some of which do not, Medeiros has developed a robust statistical model.

According to Medeiros, this model can be used to determine how different an observed black hole is compared to those predicted by the model of Einstein’s theories, thereby providing support for one theory or another.

Medeiros’ models will be tested in the coming years as UA researchers collect data from the international Event Horizons Telescope, which has stations all the way to the south pole collecting data about the black hole at the center of our galaxy.

The UA also received a national Partnerships for International Research and Education grant to establish the computing infrastructure necessary to process and share this data.

Medeiros has presented her work at the American Astronomical Society and will publish her results in The Astrophysical Journal.

Even with her success, Medeiros’ path to graduation has not always been an easy or straight one.

“As a woman in STEM, I have faced obstacles, but I have worked hard to solve these problems, been involved in women’s physics organizations, and mentored younger students,” Medeiros said.

Medeiros also had some advantages. Her firsthand experiences of culture shock as a child helped her deepen her international collaborations.

Reflecting on her scientific career so far, Medeiros credits her stubbornness for her success.

“Half the time people tell me I am a genius when I tell them what I study. I think this stereotype can be very harmful and discouraging to younger students, since most people don’t really think of themselves as geniuses,” Medeiros said.

“You don’t have to be a genius to do what I do. You don’t have to understand everything the first time you see it in a class, but you do have to be willing to put in the time and work until you do.”

Follow Randall Eck on Twitter