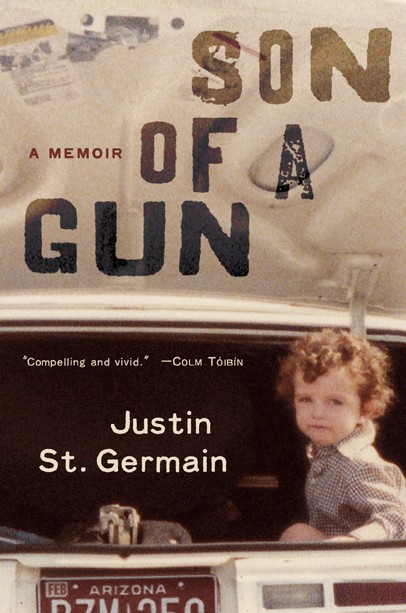

In the opening pages of his memoir “Son Of A Gun,” Justin St. Germain quotes famous American literary writer, Henry James, as he numbly searches for words to state what has just happened to him. His mother is dead, his stepfather shot her and there’s nothing he can do to change it.

“My mother is dead. The beast has sprung,” he writes.

St. Germain recalls that day, Sept. 20, 2001, as beautiful. He’s a 20-year-old UA student, riding his bike home against traffic on a hot summer day. He describes the “bright expansive sky” as he passes familiar university markers — Greek Row, Speedway Boulevard and the stucco neighborhoods surrounding campus, unaware of the news waiting for him at home.

“She’s dead,” St. Germain’s brother, Josh, told him after hearing the news over the phone from the family friend who found their mother’s body. “Mom’s dead.”

St. Germain, 32, describes his mom, Deborah, as “the toughest woman I’ve ever known.” She was 44 at the time of her death and married to her fifth husband, an ex-cop named Ray whom St. Germain likens to Wyatt Earp, referencing striking similarities between the two men’s personalities. St. Germain and his mother lived in Tombstone, where he spent much of his childhood and teenage years. Although St. Germain doesn’t attribute his mother’s death to the famous Western town, he doesn’t deny its relevance.

“You’re talking about an area that’s specifically a town that makes its living off of reenacting and celebrating a gun fight,” St. Germain said. “I do think on some level … that it kind of affects the mentality of a place.”

Hear audio of St. Germain’s interview on our multimedia page.

While St. Germain tells his rendition of his mother’s story, he rediscovers police reports and former acquaintances while drawing attention to bigger issues: guns, violence and misogyny.

“It’s not the victim’s fault for being a victim of violence,” St. Germain added. “They’re often treated that way. A lot of questions I get are, ‘Why didn’t she leave? Why didn’t she do this or that?’ As if it’s somehow her fault. It’s really easy to find yourself in that situation, where you can be subjected to these terrible acts of violence, and I think it’s a lot more common than people acknowledge.”

In the years following his mother’s death, St. Germain completed his undergraduate degree, pursued his master’s at the UA and eventually was chosen for the Stegner Fellowship at Stanford. St. Germain left Arizona with the intention of never looking back.

“When I left Tucson, I had been living there for seven years … I really wanted to get out; I thought I was done with it,” he said. “But if anything, I was more preoccupied with Arizona and Tombstone, especially.”

St. Germain focused on fiction writing at Stanford, including a short series set in the southwest among several others that he said he didn’t feel a connection to. It wasn’t until a professor at Stanford encouraged him to investigate and write about his past that St. Germain began to write the memoir.

“By the time I started writing it, she had been dead for almost seven years,” he added. “It was almost as if she had never existed. Nobody talked about her; it just seemed like this weird thing where I remembered it … but then it was almost like it hasn’t even happened at all … I wanted to make sure that her story didn’t get completely forgotten.”

St. Germain said he was initially nervous about sharing the story with the world, not for the sake of himself, but for his mother.

“I didn’t really care as much about putting myself out there and honestly I didn’t care that much about my surviving family,” St. Germain said. “I was pretty concerned about the idea of putting my mother’s life out there. In some ways it’s easier to write about dead people and in some ways it’s harder, but it’s kind of the same reason behind both because they can’t speak for themselves.”

The memoir also brings light to the issue of gun control, specifically in Arizona. As for St. Germain, he said he does not favor a side, but does still keep a gun at his home in Albuquerque, N.M., where he teaches creative writing at the University of New Mexico.

“I don’t love guns, don’t belong to any organizations, don’t have any bumper stickers,” St. Germain writes, “but I sleep with a loaded shotgun under my bed for one simple reason: in case there’s a man at the door who means me harm … Nobody ever wins the argument. They don’t believe in the man at the door. I do. I’ve met him.”