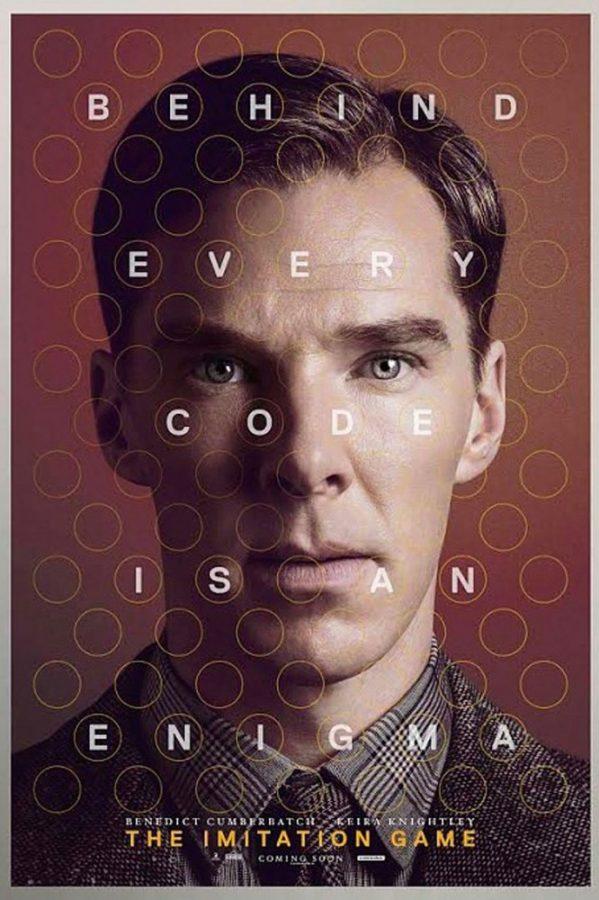

“The Imitation Game,” the awards season’s darling biopic of British mathematician and code breaker Alan Turing (“Sherlock’s” Benedict Cumberbatch), attempts to play its own “imitation game” with the audience.

One of the first exploratory forays into artificial intelligence, a field that Turing pioneered, involved a simple game where a third party had to determine the sex of two unseen participants, their only method of communication being written notes. This would give rise to more complex tests involving computers imitating humans, blurring the line between the intelligence of man and that of machine.

The film, and Turing himself, via direct address to the audience, asks the viewer to judge him on his actions and character during World War II.

It’s a provocative question to pose, especially with Cumberbatch’s arresting delivery, instructing the audience to look closely, pay attention and reserve judgments until the very end. However, there’s really not a lot of moral ambiguity in Turing’s case; the movie comes down squarely on his side — for good reason. Turing’s legacy has a single black smudge, though not through any fault of his own. He was homosexual, which was a crime in Britain at the time.

It is the beginning of World War II, and the Allies are not faring well against the Axis. The Germans encrypt all of their radio communications using Enigma machines, rendering all messages frustrating gibberish to the Allies. Everyone believes it is uncrackable. The precocious Alan Turing puts forth that they will know for sure whether it’s unbeatable only once he’s had a crack at it. He, along with a team of Britain’s best and brightest mathematicians, linguists and cryptographers, hit their heads together, and sometimes hit each other, in a daily sprint against the clock. Enigma changes every day.

Turing is presented as the classic socially awkward genius. His condescension toward his colleagues stems from both his social ineptitude and the belief that he is, indeed, better than everybody else.

Both Cumberbatch and director Morten Tyldum strike a balance with Turing between “likeable” and “unlikeable” that only just tips in favor of “likeable.” Though he may be brash, both accidentally and purposefully, it feels validated, as he really is the smartest one in the room. His inability to pick up on social cues sometimes manifests itself humorously, as he attempts to tell a joke in deadpan delivery, and sometimes tragically, as he struggles to accurately express himself through the occasional stutter. For all of his eccentricities, Turing’s heart is in the right place. He just wants to win the war, which would also give him the pleasure of solving his greatest puzzle yet — Enigma.

However, these aspects described may be exaggerated. This awards season has brought into the forefront the tricky nature of the phrase “based on a true story.” “Selma,” “Foxcatcher” and “The Imitation Game” have each had their fair share of various parties coming forth claiming distortions and inaccuracies.

In this particular case, historians have laid claim to a litany of potential falsehoods. An aspect that seems so inherent to the film’s conflict and characters, Turing’s social struggles, is claimed to be highly exaggerated. If Turing did indeed get along in general with his coworkers, as is put forth by scholars, the film paints a much different picture.

The characters and stories presented in the film ring true, yet, if major aspects are altered, how should that affect criticism? The details may be far from the truth, but the general form seems to be true: a genius that nearly single-handedly won World War II, a man who later committed suicide after his closeted homosexuality came to light and was punished by society for it. At times, a paradoxical way to pay homage to someone’s life is to alter it.

Grade: B

_______________

Follow Alex Guyton on Twitter.