As the UA awaits its first shipment of H1N1 vaccinations, Daily Wildcat back issues show this isn’t the first time campus has braced itself against a strain of the dreaded swine flu.

In October 1976, UA students turned out by the thousands to be inoculated against a strain of swine influenza that then-President Gerald Ford’s administration believed might turn into a deadly pandemic — one that never materialized.

Earlier that year, an article by The Associated Press in the March 25, 1976, issue of the Daily Wildcat reported Ford’s announcement of a plan to vaccinate every American by November of that year. “”We cannot afford to take a chance with the health of the country,”” Ford said, adding there was “”no cause for alarm.””

“”The reaction, I am told, may mean a few sore arms for a day or two,”” he said.

Administration officials feared a similar pandemic to the flu strain that killed 548,000 Americans between 1918 and 1919.

Fear of a possible pandemic started with a swine flu outbreak among military recruits at Fort Dix, N.J., in February of that year. According to a history by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, government researchers deemed the threat serious enough to recommend nationwide vaccination.

After convening with a large group of well-known scientists and public officials, including Jonas Salk and Albert B. Sabin, who pioneered the polio vaccine, Ford accepted the centers’ recommendations and announced a $135 million vaccination program.

But not all went according to plan. An article from The Associated Press in the Oct. 13 issue of the Daily Wildcat reported that eight states halted their vaccination programs when three elderly persons in Pennsylvania died after receiving the flu shots.

All three were in their seventies and died of heart attacks after being vaccinated within an hour of each other in Pittsburgh, the article said.

The deaths came less than two weeks into the national vaccination campaign, causing a media frenzy, according to the CDC’s history of the 1976 vaccination program.

An article from The Associated Press in the Oct. 14 issue reported that the Food and Drug Administration could find no link between the swine flu vaccine and the deaths of at least 24 elderly people across the country who died after taking the vaccine.

The CDC attributed the deaths to natural causes, issuing a statement saying there were 11.6 deaths per hundred thousand every 24 hours for persons between the ages of 70 and 74.

“”There is no evidence that the program should be curtailed in anyway,”” a CDC spokesman said.

The Daily Wildcat reported in the same issue that vaccinations would occur on schedule at the UA and in Pima County, with county health director Ted Scallione saying that reports on the deaths had caused “”an unwarranted scare.””

“”You would have to search pretty deep to find a connection between swine flu vaccines and a heart attack,”” Scallione said.

Gary Carl, a research assistant in microbiology at the College of Medicine, also tried to tamp down fears, suggesting people “”hang loose”” until better evidence of danger could be produced.

In the next day’s issue, The Associated Press reported that most states that had cancelled were preparing to resume their clinics.

Dr. Theodore Cooper, a senior government health official, also noted that the vaccine’s target population, the elderly and the chronically ill, were far more likely to die of heart attacks regardless of being vaccinated.

Even so, the Oct. 21 issue of the Daily Wildcat reported light turnout for the first day of swine flu vaccinations at the UA, with only 2,200 people receiving vaccinations.

The Student Health Center was supplied with enough vaccines to inoculate 20,000 people, the article said.

Allie M. Nelson, nursing supervisor for the Student Health Center, told the Daily Wildcat she believed media attention surrounding the deaths in Pennsylvania was responsible for suppressing turnout.

She also blamed city publicity, which announced the clinic dates as Thursday and Friday, instead of Wednesday and Thursday.

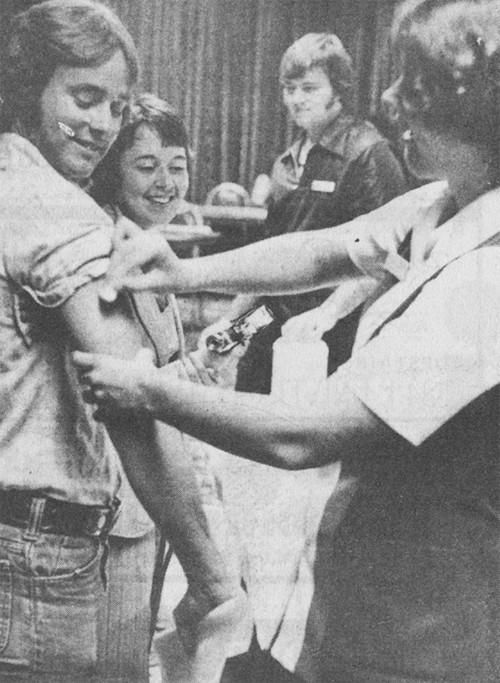

The Daily Wildcat reported that those in attendance took their medicine well.

“”Although reactions from recipients of the vaccine varied from quick grimaces to surprised smiles, most of those inoculated agreed the injector-gun vaccinations were painless,”” the article said.

Students from the colleges of nursing and medicine administered the vaccinations with an injector-gun that forced the vaccine into the body through pressurized air, rarely breaking the skin, the article said.

The vaccination clinic did double duty the next day, vaccinating about 4,600, leaving campus officials thrilled.

“”Kids went home and talked to friends who’d had shots,”” Nelson told the Daily Wildcat. “”They figured if their friends were feeling OK, the shots must be OK too.””

However, the immunization program was eventually halted after scientists discovered Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune disorder affecting the nervous system, in about 500 of those who had been vaccinated. This discovery, combined with the fact that H1N1 did not appear to be spreading across the country, led the government to discontinue the vaccination program by Dec. 16, 1976.

Four days later The New York Times published an editorial dubbing the year’s events “”The Swine Flu Fiasco.””

The Daily Wildcat was off for a long, and presumably healthy, winter vacation.