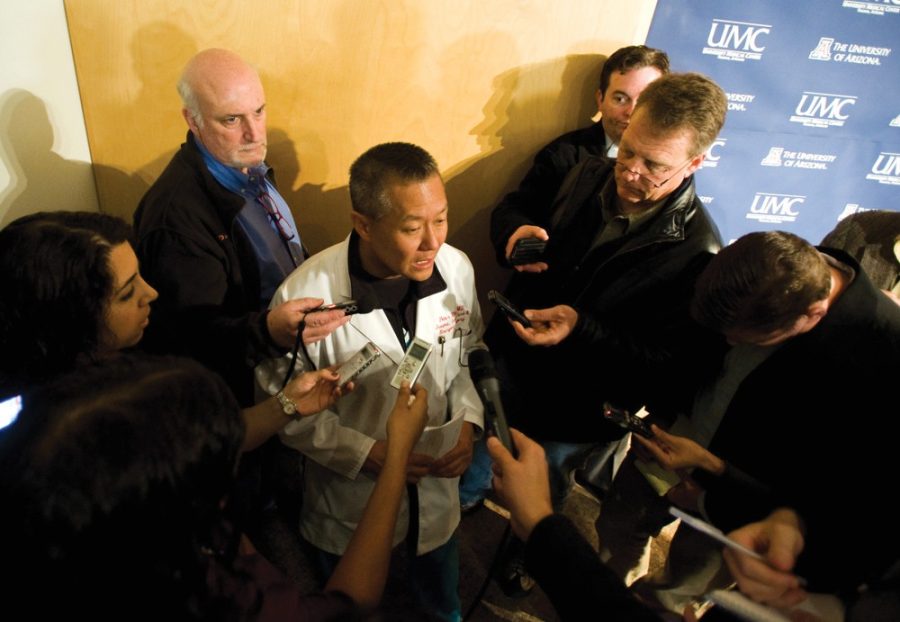

Dr. Peter Rhee has spent his career saving victims of violence. He served 24 years as a Navy surgeon, patching up battlefield injuries, and is currently the chief of Trauma, Critical Care, Burn and Emergency Surgery at Banner–University Medical Center, as well as a professor of surgery at the UA. We sat down with Rhee to discuss his life on the other side of these tragedies and his experience as the attending physician during the 2011 Tucson shooting.

The Daily Wildcat: What makes gun violence a personal issue to you?

Rhee: I deal with it every single day. It’s amazing to me that I go into this isolated world and I am kept a secret. I’m kept a secret because the public doesn’t want to hear about it. They just tell me to take care of all these ridiculous bloody shots. You know, why don’t you come into the hospital for about a month and look at all the people that are shot, and look at why they’re shot. And look at the stories behind each human being that is shot. Some of them are mad people, most of them are not.

What are your thoughts about the Tucson shooting in 2011?

Senseless. It had no purpose, but we do love our guns, and we can get guns. I think this is a political issue. I don’t think the people are actually for the banning of guns—of course that will never happen. In this country, guns are ubiquitous. There is no way to do that. To be … absolutely on one extreme and say anybody can get it without any regulation seems a little silly, but I cannot get onto a little airplane to fly anywhere without going through all that security. … There’s got to be a fine line in there somewhere, right? People force you to wear seatbelts, people force you to buy car insurance and people force you to stop at a red light.

What other parts of the world do you see gun violence becoming a serious issue in the future?

Well, I haven’t seen the world. But when you go to other countries, most of them have no interest in that because they just don’t see gunshot wounds. Back in Korea, for example, I think they saw one in five years. And that wasn’t even a person shot in Korea, it was a Navy captain that was shot when his ship was hijacked in the Middle East. And it made national news and [was a] sensation because one of the key trauma surgeons in that country was trained in the U.S., and cared for him after his initial gunshot wound. If you go to Japan, it’s also unheard of. … When you go to Europe, most countries have really never had a gunshot wound. … In comparison to other parts of the civilized world, basically Europe and Asia, unless you’re at war you don’t see gunshots.

Why do you think gun violence has become an increasingly serious issue in the U.S.?

Yesterday, I was on call and I took care of a gal who shot herself in the brain, and we’re going to try to take her organ for donation today. But every time a person tries to kill themselves, in the U.S.—and these are young people—most of the time they are associated with situational depression, at least with females. And, sadly, most of them involve men or some sort of a romantic encircle. But when you take a bunch of pills or try to kill yourself one way or another—you can find ways to overcome that. You can have a return to a bountiful life, but when you put a gun to your head, most of the time that is irreversible for you.

What are the most frequent gun violence cases hospitals receive in the U.S. or globally?

Be aware of [the] commonality and frequency of these injuries, and the stories and healing stories behind one of these gunshot wounds. In this city, unusually more than any other city, they hide this information. They say the patient was taken to a local hospital, they don’t say much more about it. The lay public has become numb to the gunshot wound, and they just discount it. … You know, when we talk about breast cancer, breast cancer, breast cancer, all the time—we do something about it. When we talk about red light running and texting and driving, we do something about it. We don’t talk about the gunshot wounds. It is politically intense. It is difficult for us to talk about it. We don’t want to talk about it. Sometimes they are seemingly similar stories, but a lot of times they’re not.

How does the health care system today respond to gun violence?

Well, we treat anybody that comes into our floor. What I wanted to do is have people who carry guns and who have bullets understand that, while it’s right that it’s expensive in terms of lives and friends and family, it’s also expensive to health care. I want a public system somehow to pay for this, because the care we provide—whether you go to a tombstone because of a shot to your head or you’re the girl who put the gun to the head, or a victim of violence— … you will need trauma surgeons. And when you come to the trauma center, we’re ready for you. But the lay public, everybody who pays taxes one way or the other pays for that care.

How much responsibility do our mental health care institutions carry over to gun violence?

They have a part to do with it, but most of the people who inflict gunshot wounds are not mentally ill. … The people who go into a theater or a grocery store, sure they’re mentally ill. But we get … shootings every single day. Every day. There aren’t enough mentally ill people. These are for people treating their guns and shooting themselves and people shooting other people—people who think that they’re protecting their home—but you end up getting shot because they pulled out a gun. We have people shot every day for one reason or another, and that’s the story the public needs to hear over and over again. As long as the public makes an informed decision. … I live in a society where I don’t make the rules. I follow the rules. Whatever my society tells me are the rules, I will follow. If they say they want to have guns, then that’s fine. But do they know the consequences? I mean, to this day, people go to the store to buy bullets because people are still so paranoid about losing their ability to protect themselves, so they stockpile their guns and bullets. Now I would like to see a penny tax on their bullets. And that penny tax should go toward three systems: the police system, the court system and the health care system. This will take care of people who are shot. I’ll be happy to take care of you if you shoot yourself or shoot somebody.

Can you describe some issues or perspectives about gun violence our media could give more attention?

Yeah, that gun violence is not what is portrayed. The gun violence is the availability of guns, and they will be used. If you pick up a rock, that rock will be used. If you pick up a knife, someone’s going to get stabbed. If you pick up a gun, someone’s going to get shot.

How do you think we as a society can improve our response to gun violence?

Well, I don’t know if there’s a way to improve. I just think that the people need to be aware. I think that’s where we start. You start with data. You start with information. You try to make the best choices you can. In this society, in this city, it’s fine with the volume of people being shot every day, and that’s the price you want to pay. I don’t have an issue with them. You know, that’s not my decision. And I’m not a politician—I’m a doctor, I’m a public servant. I will take care of whatever you want me to take care of. But as long as people know what’s going on. When the public decides what they want to do, when the politicians decide what they want to regulate.

Follow Pearl Lam on Twitter.