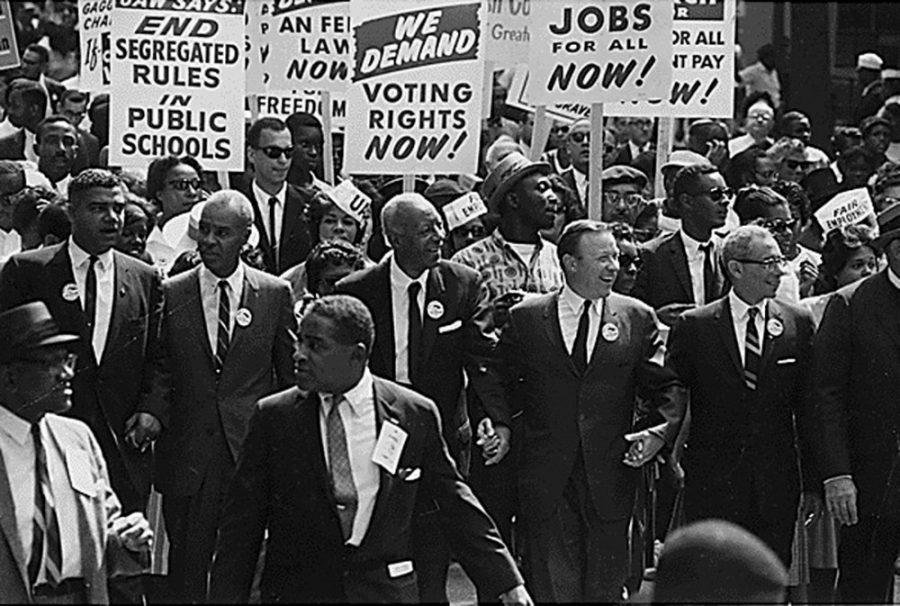

There was no Selma march. No historical speech from Martin Luther King Jr. No rallies that drew national attention. But deep in Arizona’s past is a litany of stories about the roles African-Americans played in the state’s history.

With February being recognized as Black History Month, it is important to take time to recognize stories of great African-Americans that contributed to the state’s development.

The African-American history of Arizona began in 1528 when a former slave named Esteban came to the land now known as Arizona. According to the Arizona Historical Society, Esteban was a slave to a Spaniard until he left on a Spanish expedition to discover the New World. While the fate of Esteban was uncertain, numerous historians still recognize him as the first African-American to step foot on Arizona soil.

Fast forward 400 years, and the number of African-Americans who resided in Arizona grew to 2,000, according to Keith Crudup’s dissertation “African Americans in Arizona: A Twentieth Century History.” Many migrated from the South in hopes of new opportunities and potential work. However, the move did not eliminate the presence of segregation that had swept across the states.

“Segregation was as entrenched in Arizona as anywhere in the South,” said Thomas Sheridan, in his book “Arizona, A History.”

With the Arizona Legislature enforcing segregated schools, the entire state separated everything from blacks and whites, including churches, banks, hotels and more.

Sheridan quoted Lincoln Ragsdale, a civil rights activist, saying, “Phoenix was just like Mississippi. People were just as bigoted. They had segregation. They had signs in many places, ‘Mexicans and Negroes not welcome.’”

Although the segregation was prominent, African-Americans continued to fight for their rights and equality. Through this struggle, prominent leaders rose to the occasion to represent African-American culture and what they are capable of.

In 1933, Elgie Mike Battaeu was the first black woman to graduate from the UA. She received a master’s in education after already completing her undergraduate degree in Texas, according to the Arizona Historical Society. Battaeu taught at segregated schools in both Tucson and Phoenix before becoming the first African-American to serve on the Pima Community College governing board.

Cloves Campbell Sr. was the first African-American to be elected into the Arizona State Senate. After receiving a degree from Arizona State University, Campbell was a member of the House of Representatives for two years before running for the Senate seat. According to BlackPast.org, Campbell was the first legislator in the nation to propose a holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Although he was denied the holiday initially, the African-American community continued to fight for the holiday until it was put to vote and passed in 1992.

Arizona was the last state in the nation to approve the holiday, and that only happened after voters first defeated it and then, two years later, passed it through the initiative process. A previous governor had killed an early governor’s decision to celebrate the day.

This need for the people’s vote to create a holiday came from the lack of support in the Legislature. Since Campbell Sr. first began the discussion, the bill had been nearly approved but was then denied countless times.

State Historian Marshall Trimble said in March 1991 the NFL voted to move the 1993 Super Bowl out of Tempe, due to the state’s stance on the holiday. The NFL then proposed that Arizona would be given the 1996 Super Bowl under one condition.

“The message was clear,” Trimble said. “Pass the MLK holiday.”

This movement from the NFL is what ultimately led the Legislature to put the holiday in the hands of the public. The vote was 61 percent in favor, according to Trimble. Campbell Sr.’s dream of his state celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. finally came true 20 years after he initially proposed it.

In 1946, coach Steve Coutchie and the ASU Sun Devils made historical changes to their football team as they added two African-Americans to their roster. According to Trimble, Morrison “Dit” Warren and Joe Batiste returned from World War II and used their GI Bill to continue their education and play for ASU. At the time, ASU was a part of the Border Conference that included teams from New Mexico, Arizona and Texas.

According to Trimble, when it was time for ASU to play the Texas schools, the schools said they refused to let blacks play on their fields. The reaction from ASU is what made history. The Sun Devils refused to exclude their black teammates, and the student body urged their athletic department to take a stand. The athletic department declared that it would not play against any school unless the entire team could play. In the end, only one Texas team agreed to the terms.

The UA also had an athletic leader who not only made history in the state but in the nation.

Fred Snowden, an Alabama native, was the first African-American to be hired as a coach of major college basketball team in 1972. According to the Tucson Citizen, it was Snowden who grew the Arizona basketball program from 3,000 seats in Bear Down Gymnasium to the 15,000 that were built in McKale Center.

While his first seasons were more about turning the program around, Snowden finally claimed victory as he led the Wildcats to win the Western Athletic Conference championship in 1976. This made Snowden the first African-American coach to win a major conference championship, according to The New York Times.

People looking to take part in Black History Month in Tucson can do so as the UA’s African American Student Affairs department presents its Black Film Festival at the Dunbar Project cultural center at 325 W. Second St. The films will run from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Feb. 21. For additional information about this event and other activities hosted by African-American Student Affairs, visit the department’s website.