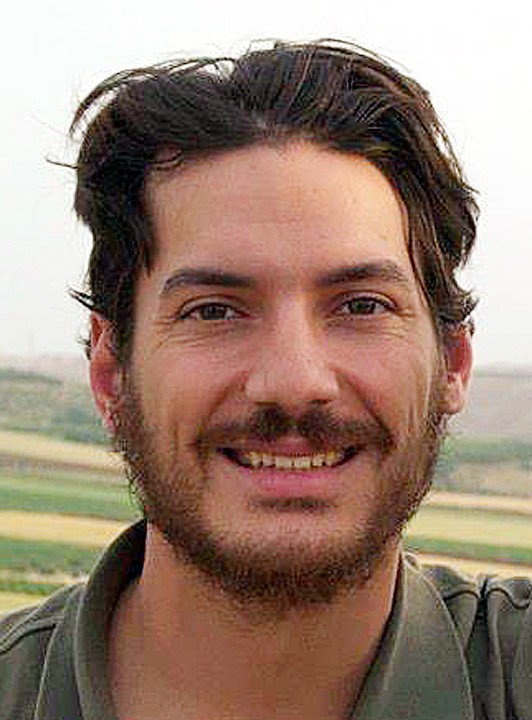

WASHINGTON — Austin Tice, a freelance American journalist who has contributed to McClatchy Newspapers, The Washington Post and other media outlets from Syria, has been incommunicado for more than a week, his whereabouts unknown since exchanging email with a colleague.

Tice, a Georgetown University law student who served as U.S. Marine Corps infantry officer before leaving active duty in January, was one of the few foreign journalists to report from inside Syria as the civil war intensified. He entered the country in May and traveled extensively through central Syria, filing battlefield dispatches before arriving in Damascus in late July.

Tice’s reporting earned him a 2,000-strong following on Twitter, where fans of his work noted his disappearance when he stopped tweeting after Aug. 11 — when he had recounted spending his 31st birthday listening to Taylor Swift music with rebel fighters from the Free Syrian Army.

His subsequent silence didn’t raise immediate alarm because he had planned to leave that week, on a journey to the border that often takes days because of the fighting en route. The Damascus suburb where he was last known to have been has faced heavy bombardment in recent days, making communications difficult.

Tice’s family and colleagues are concerned for his safety and are asking anyone with knowledge of his whereabouts to come forward.

“We understand Austin’s passion to report on the struggle in Syria, and are proud of the work he is doing there. We trust that he is safe, appreciate every effort being made to locate him, and look forward to hearing from him very soon,” Tice’s parents, Marc and Debra, said in a statement from Houston, his hometown.

Tice’s editors said they were working with U.S. government agencies and Syrian intermediaries to retrace his movements. Colleagues praised Tice’s work, saying his experience as a Marine gave him particular insight into the capabilities of both government and rebel forces as the uprising spiraled into a civil war.

He filed one of the first detailed accounts of a battle between government forces and the guerrillas, and also wrote a piece examining the weaknesses of Syrian military tactics. Despite his close company with the rebel forces, Tice didn’t shy away from pointing out their own apparent human rights violations, such as prisoner abuse and alleged executions. Apart from McClatchy and The Washington Post, Tice also contributed to CBS News, Al-Jazeera English, the Agence France-Presse news agency and the MCT Photo Service.

He maintained a wide range of contacts via email and Skype, the Internet communications service. He reached out to Middle East experts and specialists on insurgent and jihadist movements. None has reported contact with Tice since mid-August.

Tice had entered the country through a rebel-held area and was there without a visa, as is typical of many foreign journalists covering the conflict.

Caught between the government’s shelling and the attacks of a shadowy rebel movement, reporters face so many risks in Syria that the Committee to Protect Journalists recently named it the most dangerous place in the world to be a journalist. At least 20 media workers — 10 professional journalists and 10 Syrian “citizen journalists” — have been killed in Syria since the uprising began in March 2011, according to the committee’s tally.

“Journalists like Austin from all over the world risk their lives every day to cover the news,” Anders Gyllenhaal, McClatchy vice president for news, said in a statement. “Austin’s reporting on the events in Syria has been particularly powerful and revealing — and a reminder of why this work is so vital,” Gyllenhaal added that the company was “deeply concerned about Austin’s safety” and was working with other news organizations and the State Department to find him. Anyone with information on Tice, he said, should contact Mark Seibel, the McClatchy Washington Bureau’s chief of correspondents, at mseibel@mcclatchydc.com.

Washington Post Executive Editor Marcus Brauchli said in a statement that the paper was “focused intensively” on bringing about Tice’s safe return.

“Austin is a talented and courageous journalist whose work has helped to shape the world’s understanding of this humanitarian and political crisis,” Brauchli said.

The Committee to Protect Journalists’ executive director, Joel Simon, said in a statement that the group is troubled by the lack of information about Tice’s whereabouts.

“His work is protected by international law, which guarantees the right to seek and receive information,” the statement said. “As a journalist, he is a civilian and must be protected from harm.”

The State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland said in a statement that the United States was working through the Czech Embassy in Damascus to learn more of Tice’s “welfare and whereabouts.”

“We strongly urge all sides to ensure the safety of journalists in Syria,” she said.

Tice was well aware of the dangers of reporting in Syria and even took to his Facebook page to beseech his friends and relatives to “please quit telling me to be safe.” He then launched into an impassioned defense of his presence in Syria, which he acknowledged was “in the middle of a brutal and still uncertain civil war.” However, he continued, he found inspiration from the Syrians he encountered.

“I’m living, in a place, at a time and with a people where life means more than anywhere I’ve ever been — because every single day people here lay down their own (lives) for the sake of others,” Tice wrote. “Coming here to Syria is the greatest thing I’ve ever done, and it’s the greatest feeling of my life.”