A new study from University of Arizona researchers highlights the potential to utilize public land and rainwater harvesting to minimize food insecurity in Tucson.

The study was co-authored by Courtney Crosson, an assistant professor of architecture at the UA’s College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture, and Yinan Zhang, a geography graduate student, as well as two others from Arizona State University.

It focused on the city of Tucson, a water-stressed, medium-sized city and known food desert. Food deserts are defined in the study as “low-income neighborhoods that have little to no access to healthy and affordable foods.”

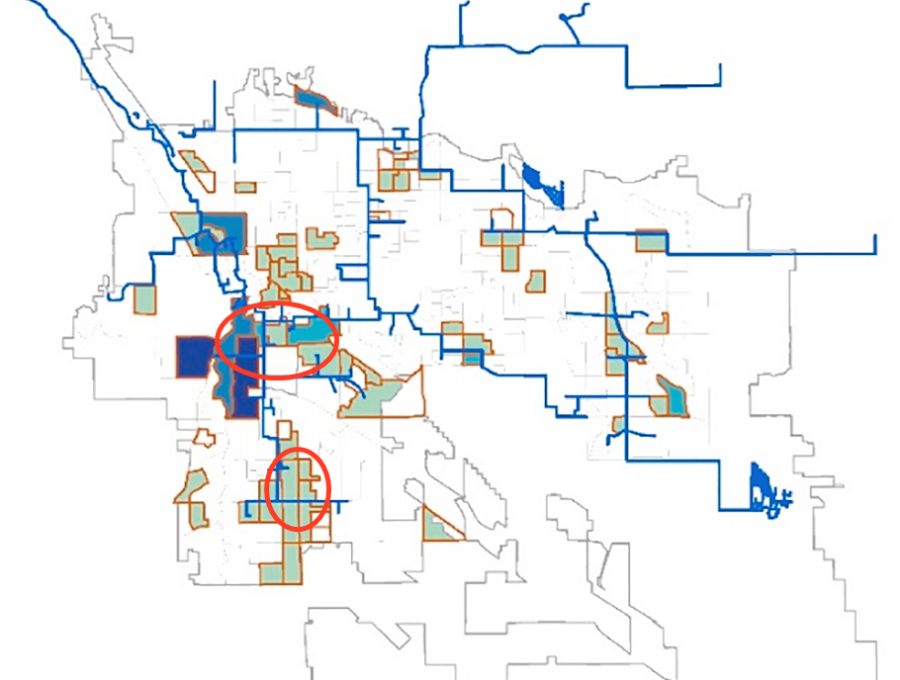

Zhang noted that some areas identified as food deserts are concentrated in west Tucson.

“The darkest area [of the map], where it has the highest vacant land per capita, should be the areas around Santa Rosa Park and Ormsby Park and the several block groups along S Nogales Highway, north to Tucson International Airport,” Zhang told the Daily Wildcat via email.

Researchers identified 711 acres of land in Tucson as food deserts and more than 1,500 acres within one mile of the food deserts that could be converted to use for urban agriculture.

“The study estimated the food cultivation capacity of vacant municipal land,” Crosson said via email. “In other words, land owned by the City or County that was not currently used and not ecologically protected. For example, many parcels were flood plain areas bordering washed. Unlike vacant land that is owned by developers or private citizens, this land is well positioned to support urban agriculture because it is publicly held.”

Crosson added that one way to incentivize cultivation of this land is for the city or county to lease it to small-scale farmers for a low price, like $1 per year.

RELATED: Tucson food trucks overcome challenges during the pandemic

If done effectively, all of the land identified by the study could be irrigated by both reclaimed water and rainwater harvesting. This decentralized method of harvesting would include equipping city rooftops with the infrastructure for rainwater harvesting and constructing large storage units to store water during dry periods.

In order to meet 100% of the nutritional needs of individuals in food deserts, food would need to be shared between neighborhoods depending on each area’s needs. With full collaboration, Crosson said that she believes the city could substantially alleviate food insecurity in food desert areas.

“In our study,” Crosson said, “results were modelled at the neighborhood block group. There were three modelled levels of community collaboration: full, only between adjacent neighborhood block groups, and none. Full community collaboration meant that any food cultivated in any neighborhood block group could be used to meet the needs of any other neighborhood food desert block group. I believe this type of full collaboration is possible with the right communication infrastructure.”

An example of what full collaboration might look like is a citywide food distribution system that delivered fruits and vegetables from the harvesting location to anywhere in Tucson.

The study originated from a request by Pima County officials looking to see how public land and rainwater harvesting could be used to minimize food insecurity in Tucson. The city is one of the poorest metropolitan areas in the U.S. and almost 18% of its population – 94,000 people – lives in an area classified as a food desert.

Follow Kristijan Barnjak on Twitter