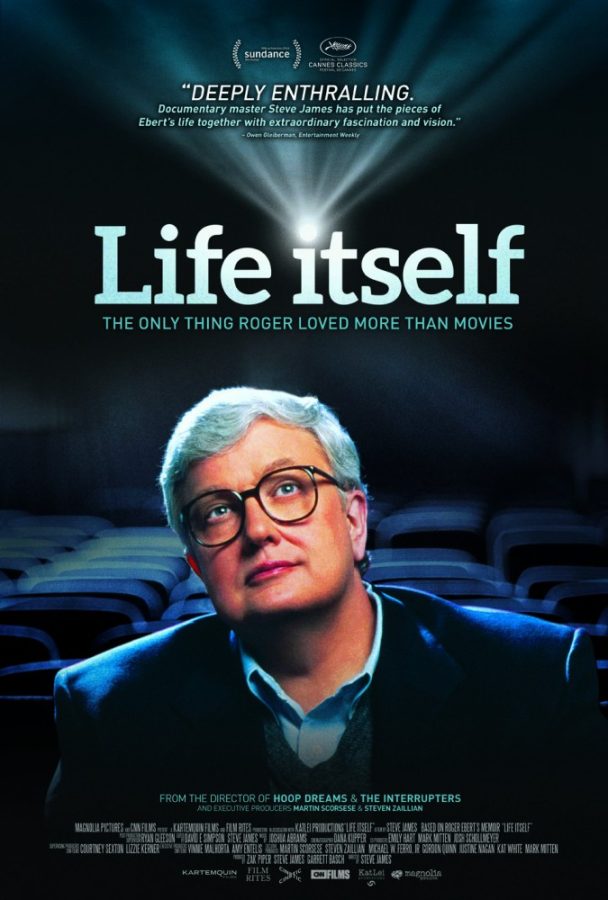

Chances are, even if you are not a film aficionado, you have read a review or two from Roger Ebert in your life. Ebert died over a year ago, on April 4, 2013. Heartbreaking, illuminating, funny and enlightening, “Life Itself” is a well-balanced documentary on America’s most well-known film critic.

Director Steve James, whose 1994 documentary “Hoop Dreams” Ebert remarked as “one of the great moviegoing experiences of my lifetime,” is at the helm for this documentary. Usually directors are given a majority of the credit with the overall vision of a film, and their ideas of how a film should end up serve as a singular vessel that hopefully leads the film to safe shores. I would be remiss if I did not credit both Ebert and his wife Chaz in their paramount role in the movie. They allowed James and his crew unrestricted access to Ebert while he was in the hospital battling a cancerous, fractured hip.

Like any good actor, Ebert’s eyes are his most expressive feature. Robbed of his speaking voice, his translucent blue eyes light up with mirth or wince in pain at having to undergo taxing physical therapy.

With Ebert’s present-day struggles acting as a sort of frame for the story, we weave back and forth, in and out of his life. Our through line is narration from Ebert’s 2011 memoir of the same name.

There’s a good amount here that treads previously-covered territory to those familiar with Ebert. We begin with his childhood, an only child to two supportive parents. He was a staunch fixture in the newsroom for The Daily Illini at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and had a meteoric rise to the top, becoming the film critic for The Chicago Sun-Times in his early 20s. He won an unprecedented Pulitzer Prize as a film critic, and squared off against his rival (yet ultimately, best friend) Gene Siskel on the television show “Siskel & Ebert” as the two traded heated views over the current week’s fare of new movies.

Noted luminaries of the film industry drop in. The New York Times film critic A.O. Scott, Time film critic Richard Corliss and famed filmmakers Martin Scorsese, Errol Morris and Werner Herzog are among the many talking heads that speak on Ebert.

But this is not simply a film about the events of Ebert’s life as it delves into so many other fascinating areas. There are comments on film and film criticism, including the changing landscape and ideologies of both over the years. Of interesting note is the column Corliss wrote in the March/April 1990 “Film Comment” that the documentary highlights. The article derided Ebert’s and Siskel’s brand of “thumbs up/down” criticism, and Ebert responded with an article of his own.

This is but one example of how the film successfully navigates the tough task that all documentaries face: lack of bias. It could be very easy for director James to fall into piling nothing but praise on Ebert, the man who so highly praised James’ work. However, both James and Ebert know a good film reveals all sides and sympathies to a situation or a person. Thus, we have detailed accounts of Ebert’s alcoholism in his initial years at the The Chicago Sun-Times and chronicles of his pig-headedness, petulance and bravado as he verbally sparred with Siskel. In the hospital, Ebert sucking fluid through a tube in his neck with a windy, desperate gurgle is one of the toughest things you’ll see in the cinema this year.

Even with all of this, the film does seem to favor Ebert.

One of the final questions James asks Ebert in their correspondence is, “Why did you call your book, ‘Life Itself?’” Ebert’s response: “I can’t.” It would be too easy for us to be given an answer. It would be like asking God, “What’s the meaning of life?” We can’t have an answer, but we can take a pretty good guess at the whole thing. Anyhow, Ebert probably knew the answer to both.

“Life Itself” opens at The Loft Cinema on July 18.

Rating: Two Thumbs Up