Eric Plemons, a University of Arizona assistant professor of anthropology, wasn’t planning on studying schools of thought behind facial feminization surgery (FSS). That was until he met the doctor who first developed FFS and became fascinated with how understandings of gender shape medical procedures.

In 2010 and 2011, Plemons interviewed two doctors and many patients. He sat in on clinical consolations and surgeries, collecting qualitative data. He said two main schools of thought emerged based on the question of what transgender people need from medicine.

“The one that says, ‘You should be the person you want to be’ and ‘Let’s sit down together and talk about what your features look like and what your goals are,’ that’s more turning the question of masculinity or femininity to the patient themselves,” Plemons said.

That approach, according to Plemons, is based on the understanding that transgender women want what all people want from cosmetic surgery: to be their most authentic self.

The other understanding is based on mathematical norms of what is masculine and what is feminine. The dimensions of “normal” features are derived from databases of measurements from other surgeons and researchers.

According to Plemons, that divergence in thought is what makes his study, published in Medical Anthropology 2017, useful. The philosophies behind the two styles of FFS aren’t based on personal preference but on an understanding of what doctors are supposed to do for patients.

RELATED: U of A Consortium on Gender-Based Violence Launches Their First Annual Conference

Plemons said any time someone goes to the doctor, there are three questions: Why are you there? What can the doctor do to solve that problem? And how effective was the solution?

“If you change the first one, then all the rest of them change, too,” Plemons said. “If I change my understating of why you’re here, then I also change what’s an appropriate response and how I know I did it right.”

Those differences have implications clinically, financially, ethically and institutionally, according to Plemons.

“The ‘why’ and ‘what’ in trans- medicine has never really been settled,” Plemons said. “People are always debating it.”

Russ Toomey, associate professor of family and consumer sciences, said there are also significant social consequences to FFS, as research has consistently linked diverse gender identities and expressions to heightened risk for victimization or discrimination from families, peers, communities and society.

“If one’s gender identity – regardless of whether the person identifies as transgender or cisgender — aligns with the gendered perceptions and norms of others in society, they are likely at less risk for rejection and victimization,” Toomey said.

Judith Butler, an American philosopher and gender theorist, wrote that gender is performative. This means gender comes from social recognition and social actions, not genitalia. This “truism” helped shape FFS and transgender medicine, Plemons said.

“We haven’t always said gender is performative,” Plemons said. “There’s a moment where we started saying that, and it happened to be about five years before [FFS] started to become a very popular intervention.”

One question central to Butler’s theory is how ideas about what gender is influence the actions intended to produce it. Plemons said FFS is an example of the theory informing a medical practice to produce gender.

“People aren’t marching into the doctor’s office and saying, ‘Gender is performative,’” Plemons said. “What they’re saying is ‘How I look every day is having a bigger impact on how people read my sex that anything else.’”

That change in understanding about what sex is and how it’s read interrupts 30 years of transgender medicine that focused on hormones, genitals and chest structure as the definition of sex and sex change.

RELATED: Going ‘beyond the bikini’ in healthcare

According to Plemons, the popularity of FFS is rising today, though it’s difficult to get an accurate count.

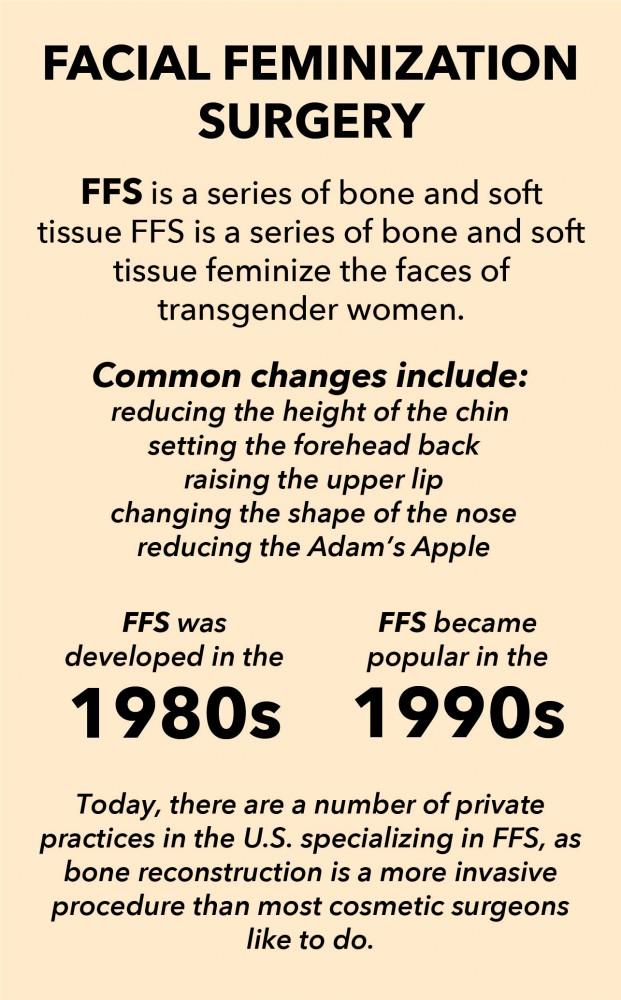

“It’s a difficult thing to measure … because it’s not necessarily a procedure but a suite of procedures done toward a particular aim,” Plemons said. “Doctors have different ways of defining if what they’re doing is facial feminization surgery or not.”

For example, if someone has a big nose, they can get a rhinoplasty anywhere, and it’s just a rhinoplasty. But if the patient is a transgender woman who sees her nose as masculine and changes it to be read as more feminine, that could be counted as FFS.

“For the doctors who are most well-known for the procedure, they emphasize that it’s bone reconstruction as well as the soft tissue,” Plemons said.

These systems of thinking, as well as the performative theory of gender, will continue to play a role in transgender medicine, according to Plemons.

“It’s not about genes, it’s not about genitals and it’s not about reproductive organs,” Plemons said. “It’s about social presentation.”

Follow Marissa Heffernan on Twitter