The UA Tree-Ring Laboratory was founded by an astronomer, directed by a ship hull specialist and is going on more than 70 years in what was supposed to be its temporary home under the football stadium.

But in a year and a half, more than two million samples covering 8,000 years of history from around the Southwest will be moving to their new home.

The building is in the design stage right now, and is slated to break ground in April or May of this year, according to the lab’s curator, Pearce Paul Creasman. The new laboratory will be built to connect to the Math East building, and the expected completion date is the fall of 2012.

“”That’ll be great because that’ll give us a new home,”” Creasman said.

History

In 1937, A. E. Douglass, an astronomer at the UA, was comparing solar variations and sun cycles to patterns on tree-rings, a course of study, which brought him little success. And so the field of modern tree-ring dating, dendrochronology, was born, which scientifically allowed meteorologists, archaeologists, anthropologists and astronomers a method of dating events in time. Historical dating is also what brought Creasman to the lab.

Creasman, during years of research in Cairo studying boat hulls, realized the importance of tree-rings in his research. With most boats before 1850 constructed out of wood, the lab’s research added to his understanding. A donor giving her specimens to the lab said she’d be happy to contribute her work — if they found someone to curate the lab. When Creasman heard about the job, he jumped on it.

Archaeology Laboratory

“”Before you have tree-ring data, archaeologists working in the Southwest didn’t know which group came first, who they were, how they migrated, if they migrated, if they even had a system of writing,”” Creasman said. “”Tree-ring dating is the only archaeological dating method that can give you the resolution of a single year, and sometimes you can even do better than that and get down to the season.””

Specimens are sent to the lab from around the Southwest and UA archaeologists can date lab samples to aid other scientists. Some of the archaeology laboratories most famed contributions were around Pueblo Bonito, a celebrated cultural site in Chaco Canyon, a mid-seventh century Anasazi anthropological site in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico.

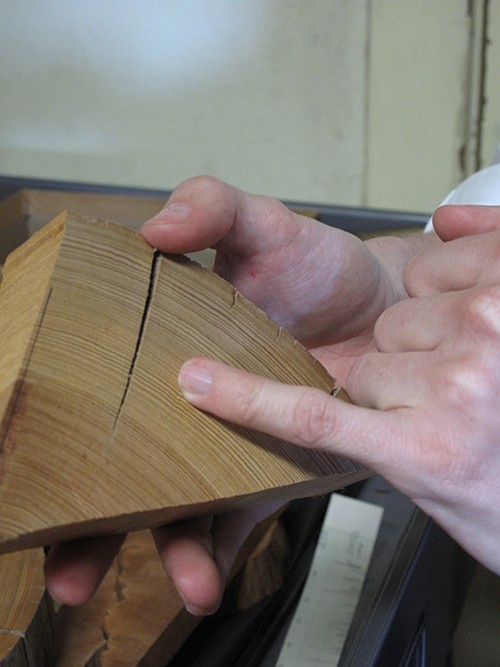

“”Statistically, if you have a big enough data set, say from 150 years, that pattern is never going to repeat itself,”” said Creasman, which allows people of various disciplines and different sections of the world to understand history more accurately, while using tree-ring research.

Specimen storage

Arizona’s dry climate provides the perfect backdrop to hold aging wood specimens. Creasman said the climate is actually the perfect preservation atmosphere. Without the lab, according to Creasman, an entire historical frame of reference would be gone forever.

Around 60 percent of their specimens are held in one room with the work of faculty from four colleges and twelve departments around campus. Chemists and physicists study heavy metals in wood. Radio carbon dating and studies of fire history have also permeated their research. Creasman said the lab even works with students from a variety of disciplines, who major in other fields and work in the lab.

“”We have three archaeologists. I study ships and shipwrecks primarily in ancient Egypt, but one does anthropological cultures and another does ancient climatology. We have ecologists, hydrologists, all kinds,”” Creasman said. “”In the tree-ring laboratory, we’ve got an amazing diversity in what faculty do.””