Two Eller College of Management researchers recently published findings of a study on the relationship between power and trust, indicating that those with less power put a significant amount of trust into those in power.

The study, titled “Power decreases trust in social exchange” and to be published in an issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was the result of joint efforts between researchers Oliver Schilke and Martin Reimann.

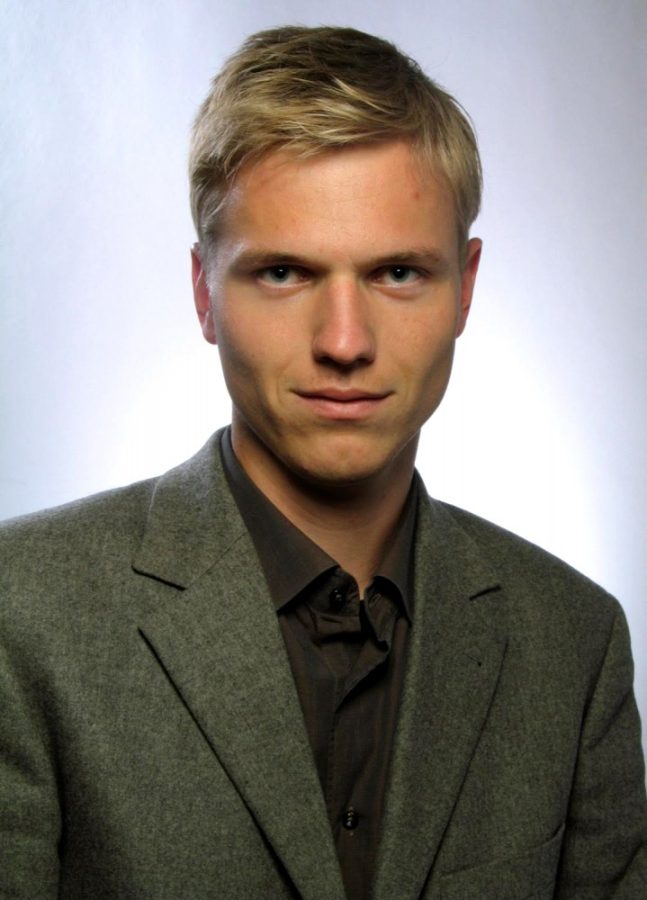

Schilke, who received his doctorate in sociology from the University of California, Los Angeles, is a current assistant professor for the Department of Management and Organizations and an assistant professor for the School of Sociology at the UA.

Reimann, who received his doctorate in psychology from University of Southern California, is an assistant professor for the Department of Marketing at the UA.

According to Schilke, power and trust are crucial features of our society.

“Differences in power characterize most organizational forms, as hierarchies can often facilitate efficient coordination; … trust is a central ingredient to social exchange and an important substitute for costly monitoring,” Schilke said.

Previous social science research, according to Schilke, had mostly neglected to systematically address the relationship between power and trust and whether one’s power position has an effect on the trust that one places.

This gap in knowledge encouraged Schilke and Reimann to further delve in to the relationship between power and trust.

“The lack of prior research was particularly puzzling to us, as a lot of relationships in which trust is crucial involve stark power differences,” Reimann explained.

According to Reimann, relationships such as those between patients and doctors, students and professors, and employees and supervisors are all examples in which the individuals involved have stark power differences.

“We suspected that having low versus high power would have a significant effect on one’s trust in such relationships, but couldn’t identify prior empirical research that would directly speak to this issue,” Reimann said. “However, we were able to derive competing predictions from two different theories.”

The first theory used, the rational actor account theory, suggests that people will only be trustworthy if it is an instrumental motive for them to maintain the relationship.

“Given that powerful people tend to have many exchange partners to choose from, they place … relatively speaking, … less value in any particular relationship, reducing the likelihood that they will behave in a trustworthy fashion,” Schilke said. He went on to say that powerful individuals can afford to betray others—they can find new people to work with.

This theory goes on to state that the less powerful party, or the subordinate, knows that their superior can afford to betray them, causing them to place less trust in those who are in power.

The motivated cognition account theory, the second theory used, suggests the opposite effect.

“The theory starts with the assumption that people strive to arrive at conclusions they want to arrive at in an effort to mitigate cognitive dissonance,” Reimann said. “In particular, with increasing dependence, people will be motivated to see their partner as more trustworthy to avoid the anxiety inherently attached to their feelings of dependence.”

This theory suggests that more powerful actors should place less trust in others compared to less powerful actors.

“This research opens the door for several follow-up studies that illuminate the relationship between power and trust from additional angles,” Schilke said.

Schilke added that they expect this relationship to vary in strength depending on which culture the research is conducted in, as national cultures differ in the degree to which they find power differences socially acceptable, and such cultural values related to power distance may place an important role for the effect of power and trust.

Follow Terrie Brianna on Twitter.