It was a day that would go down in history: On Nov. 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was shot while riding in a motorcade through Dallas, Texas. Although he was taken to a nearby hospital, Kennedy did not survive. The Daily Wildcat asked UA faculty and staff, as well as a Daily Wildcat editor from the time, to share their memories from the day of Kennedy’s assassination.

Ann Weaver Hart

UA President

When news arrived at my high school that President Kennedy had been shot, I was in ninth grade gym class. The high school immediately cancelled any change of classes, and everyone stayed in place while we listened for news on the radio and received updates over the school intercom. We sat on the floor and talked quietly, not believing what we were hearing.

My immediate reaction was disbelief. We were all upset, confused and frightened as the immediate national response was a general belief that this was a conspiracy and other terrible events would immediately follow. This was the middle of the Cold War, with the constant threat and fear of nuclear attack, and I remembered the incredible fear we had recently all felt during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when we believed that a nuclear showdown between [leader of the Soviet Union Nikita] Khrushchev and Kennedy was imminent.

My most vivid memory of the days immediately following the assassination was the realization, probably for the first time as an individual, that history happened to real people in real time.

That sense of history as crisis and conflict grew over the next few years as the Vietnam War and American involvement heated up and coverage of the war dominated the television news every night, including the day’s body counts. The boys I went to school with had to register for the draft when they turned 18, and the conflict dominated our lives. The Kennedy assassination started that sense of history as world conflict and strident political debate and the U.S.’s place in the world for me.

David Soren

Anthropology professor

I was in a high school class when it happened, and it was announced on the loudspeaker that everyone would go home early.

In the bus park outside the school, people were crying and one male student became hysterical and was shaking all over. I remember that I held him for a few minutes before I got on my bus, and calmed him down.

Then, while the whole community was in shock over it, Lee Harvey Oswald was murdered right before our eyes on national TV. That was an even bigger shock for me and it seemed that the whole country was going insane and out of control. I still don’t think that Oswald acted alone, didn’t think so at the time, and remember people talking on TV at the time about how they had video footage that was confiscated and was never ever returned.

It was a really strange time for a young person to cope with, and having almost instinctively had to comfort other people despite my own confusion was an experience I had never had before.

I think it was a lot like 9/11, a feeling of sickness in the pit of the stomach. I had seen him in person when he was running for office. He was a good speaker, even with that Boston accent, and he was very handsome, much handsomer and more accessible than the candidate Richard Nixon, whom I also saw live. I remember thinking that there was very little protection for him when he came to speak to our community. You could wander right up to him.

I remember wondering about that with Gabby Giffords too, after I met her.

Mort Rosenblum

City editor of the Arizona Wildcat in fall 1963

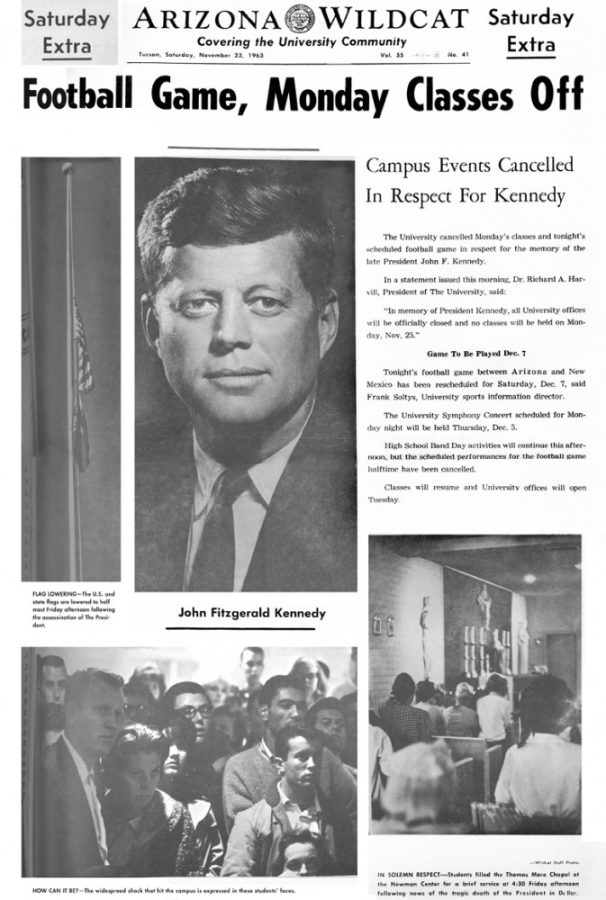

On that November day no one can forget, I was a fresh-out-of-the-box reporter working for the Arizona Wildcat. It was only a campus weekly, but under Sherman Miller, head of the University of Arizona Journalism Department, we ran it as if we were old pros. One morning, the venerable professor Brewster Campbell burst into our news-writing class, walrus mustache bristling.

“I think the president’s been shot,” he said. He hurried to the black AP Model 15 Teletype clattering away in a closet, with the rest of us in pursuit. Frank Cormier’s bulletins from Dallas confirmed it.

With hardly a word to each other, a half-dozen Wildcat people in the class rushed out the door to interview students and professors for reaction and pursue other aspects of the story.

Editors raced to our printers, who stripped everything else off their presses. Within hours, a special edition carpeted the campus. All of us knew, after that day, what we’d be doing for a living. Life sidetracked some. I got lucky. A half-century later, I’m still doing it.

Nancy Stiller

Director of Ombuds Program

I was 10 years old and in the fifth grade. Our class was reading essays that we had written and my turn to read my essay was about to come up. There was a phone on the wall in front of the room.

It rang (which never happened) and we could see from the teacher’s expression that something bad had happened. We all sat stunned as our teacher relayed the awful news that our president had been killed. She told us to quietly gather our things and go home. Many of my friends lived in my neighborhood. No one spoke as we walked to our houses. Then, the three-day vigil in front of the TV began.

It was the first time I experienced that sense of total disruption of everything that felt normal and routine. I remember feeling tremendous sadness for Jackie Kennedy and her children and for the president’s siblings, who had already experienced losing family members. There was also a police officer who was killed while attempting to apprehend the shooter. The news didn’t talk about him very much, but I felt sad for his family.

I remember so many details about that day because the events were so shocking. There was no cable TV. We had only the three major networks. All three networks covered the assassination all day long, for three days. My parents, my sister and I literally watched TV for three days straight, as did everyone.

I remember the sad funeral dirge and the clicking of horse hooves as the procession moved to the Capitol Building. I grew up in the Boston area where the Kennedy family was from. We were very proud that our president spoke with a Boston accent! In a sense, it was like losing a member of the family. I remember the sadness, anger and fear that came over us like a dark cloud.

John P. Willerton

Associate professor in the School of Government and Public Policy

I was in fifth grade. I recall my teacher being called out in the hall by the other fifth grade teacher; with our teacher out of the room we (maybe 28 of us students) were chatting, and then she returned with the other fifth grade teacher. They were both crying; they told us President Kennedy had been shot and killed, and everyone got upset. I recall some of my classmates crying. We had been in the midst of an average school day, everything had been normal, and everyone was really shaken up and we felt like our world was turned upside-down. We were all sent home pretty quickly after this. When I heard President Kennedy had been killed, I felt afraid. I remember my two younger sisters and I all feeling afraid. We wondered if other people were going to be shot; we thought about our parents and other loved ones.

Basically, to a 10-year-old, it sort of felt like the world was going wild; everything was changed, and we kids were afraid. As upsetting as 9/11 was, I guess because I was 10 years old when President Kennedy was assassinated, that was the event in our country’s history that most rattled and scared me. It hit home even more than the Cuban Missile Crisis, which had been just a year earlier and which was probably the other scariest event I recall experiencing.

Everyone was overwhelmed by the event, we were all by our TVs watching the coverage, from the time of the assassination through President Kennedy’s funeral. Since our country had not experienced anything like this since the [President William] McKinley assassination (which was well before our time), it was highly shocking. Everyone, whether or not they were supporters of the president, was very upset and — frankly — stunned.

– Follow Stephanie Casanova @_scasanova_