Graduate student leaders tackled internal debate over the graduate student bill of rights at their meeting last night, just days after the bill received a unanimous endorsement from the Graduate Council.

As the Graduate and Professional Student Council opened its meeting in the James E Rogers College of Law building room 168, two distressed graduate students spoke during the open call to the floor and voiced concern over the content of the bill, now undergoing a long series of revisions on its way to final approval.

“”After reading through it, as a graduate student I’m not comforted by (the bill),”” said women’s studies doctoral student Angela Stoutenburgh.

Although the bill includes some important clauses, its language remains too vague to offer any real assurance to the students it affects, Stoutenburgh said. She cited childcare for students as one unresolved issue the bill does not directly address.

“”I read it, and I’m still asking questions about how it helps us as graduate students,”” she said of the bill.

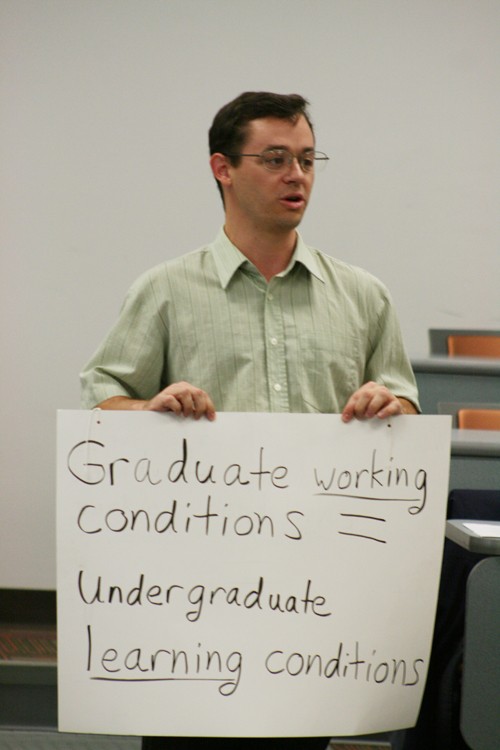

Geography doctoral student Brian Marks also voiced concerns, in this case over the bill’s lack of a defined workload cap for graduate students. The cap is desperately needed, he said.

“”Our working conditions are the undergraduates’ learning conditions,”” he said, holding a picket sign with a similar message.

GPSC President David Talenfeld, a second-year law student, responded by reminding the speakers and the council that the bill is meant to serve as a starting place for further policy negotiations and would not be able to address every issue faced by the graduate student body. Talenfeld used the US Constitution as an analogy to describe the bill’s limitations.

“”When the framers of the Constitution set out to frame that document, they understood that it was an umbrella document,”” he said. “”Like the Constitution, (the bill) will contain many unfortunate compromises. I don’t think that those compromises undermine the significance of the document.””

Talenfeld added that in order for the bill to be supported by administrators it could not introduce new policies that do not already exist in other documents. Instead, he said, the bill will bring pre-existing policies (now scattered in a disparate miasma of university documents) together as a clarified resource and point of departure for for future policy development.

“”We need a baseline document. That’s my mission: I want to provide you with that,”” he said.

Talenfeld’s statement riled some members of the council, who argued that the original intent of the bill would be undermined if it did not include more specific language to address a broad range of issues.

“”I’m just concerned that its starting to be more ‘here’s the list of rights you have’ rather than ‘here’s the rights we think we should have’,”” Jim Collins, an undecided graduate student on the council, said.

Collins focused his frustration on the removal a clause in the original version of the bill – taken out at the behest of the Graduate Council – that stipulated that if any clause in the bill violated a pre-existing university policy, the bill as a whole would not be negated as a result.

Without that clause, Collins said, the bill was little more than a policy roundup and did not constitute any progress on pressing issues.

Talenfeld responded by saying that approval from administrators, especially President Robert Shelton, was unlikely if the bill introduced new policy. It was nevertheless a step forward, he said, because it would serve as a reference and open the door for future negotiations.

“”What I’m asking you is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater,”” Talenfeld said. “”This is a document that will pass.””