SAN DIEGO — When Pfc. Geoffrey Quevedo was airlifted late last year to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center after being severely wounded in Afghanistan, his family in California was told to hurry to Washington to say a final goodbye.

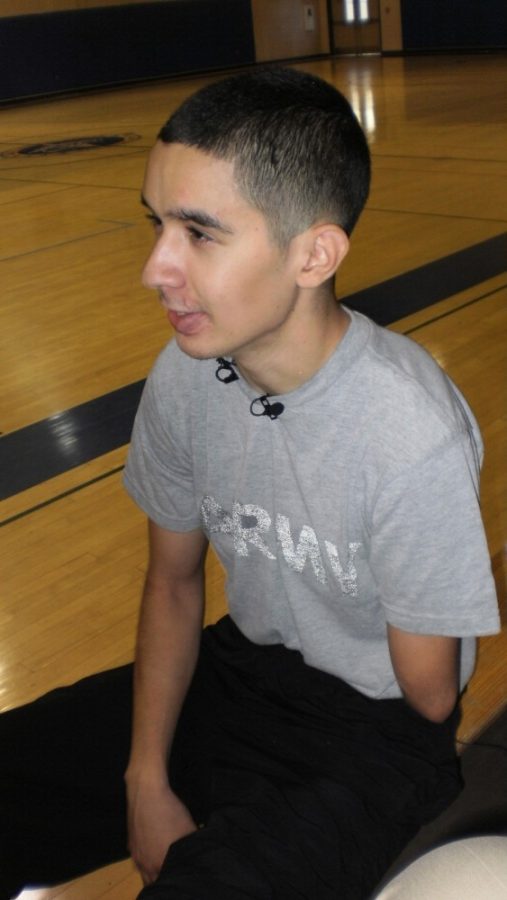

The 20-year-old from the farming community of Reedley in Fresno County, Calif., was not expected to live beyond a few days.

The blast had ripped off his left foot and his left arm above the elbow. It knocked out four front teeth, broke his nose and jaw, and collapsed a lung. He was blinded in his left eye and his blood loss was enormous.

But the doctors’ gloomy prediction failed to take into account Quevedo’s refusal to die — and possibly underestimated the military medical system’s ability to pull a young soldier back from the brink of death.

“My family was told to pack their bags and come see their son for the last time,” Quevedo said. “The doctors didn’t know something: I’m a hard head.”

Now, after a stay at Walter Reed and then at the poly-trauma unit at the Department of Veterans Affairs hospital in Palo Alto, Quevedo is receiving care at Naval Medical Center San Diego, including for traumatic brain injury.

In response to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Naval Medical Center San Diego has become one of the nation’s top hospitals in treating traumatic amputations. Since 2006, the hospital has had 169 patients who suffered amputations in the war zones.

Many patients receive more than one prosthetic, each specialized for a certain task: running, walking, exercising, etc. Last year the facility provided 418 prosthetic limbs; the number this year is already close to 500.

Quevedo is eager to get his prosthetics and, after leaving the Army, get a job. There are still surgeries and months of therapy ahead but he is doing an internship with the U.S. Marshal’s office in San Diego handling administrative paperwork.

“I never feel sorry for myself,” he said recently after a rigorous morning of exercise in a class for amputees. “I knew the risk when I enlisted. I don’t want to be treated like a baby by American society.”

He had been in Afghanistan for eight months when, as a cavalry scout for the 10th Mountain Division, he went on a patrol to clear out the buried explosives that are the Taliban’s weapon of choice. It was four days after his 20th birthday.

He does not remember much about the explosion. “I just saw a light,” he said.

The days after that are a haze, except he remembers having a dream about his 3-year-old daughter. While he has no regret about enlisting, he has a kind of sorrow that therapists say is common to the war wounded: that their injury represents a failure to do their job.

“When I woke up I just kept saying, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry that I let everybody down,’ that I could have done better on that patrol. I felt like I let my family and buddies down.”

Those feelings aside, Quevedo refuses to consider that his life will be limited by his injuries, that there are things he will no longer be able to do.

“If you tell me ‘no,’ I just say, ‘Watch me,’” he said.