One hundred years before the Black Lives Matter movement, diverse communities across the U.S. stood up in solidarity against social injustice like police brutality. Black Americans battled police brutality through the power of protests, riots and social uprisings.

According to Tyina Steptoe, a University of Arizona Department of History associate professor who specializes in race, gender and culture at the UA, the language used to describe these events can indicate biases.

“When we say uprising, it forces us to remember that this isn’t just some random outbreak of violence, that there are other issues that are provoking people in those communities to act in that way,” Steptoe said. “If we just say riot, it just seems like some people mindlessly tearing things up. But if we say an uprising against police violence, it tells you more what the purpose of it was.”

Steptoe said the difference between these terms — protest, riot and social uprising — happens to be more often about who’s doing the writing, who’s doing the describing.

The following timeline is comprised of significant historical events that lead up to the Black Lives Matter movement in chronological order.

1917 Houston Riot – Aug. 23, 1917:

On Aug. 23, 1917, several white male police officers raided a Black woman’s home, dragged her outside and brutally beat her in the middle of the street.

A young Black soldier named Alonso Edwards attempted to intervene in the altercation and was pistol-whipped by the police officers and arrested, according to the Houston Chronicle.

What ensued next was an absolute uproar over the treatment of the Black woman and soldier.

Local Black soldiers from the 24th Infantry Regiment in Camp Logan rioted throughout Houston. The 1917 Houston riot resulted in a citywide curfew the following day. The riot left 16 dead and 22 injured, most of whom were white citizens, according to the Houston Press.

The Houston riot led to 63 soldiers receiving life sentences in prison and 13 soldiers being hanged. No white civilians were brought to trial, the white officers faced courts-martial but were released, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

RELATED: Black Voices of Tucson: Eller African American Honorary at the University of Arizona

“It was over 100 years ago. And I keep seeing glimmers of this — again and again — today. When you put all these examples [of social uprisings] together, the root of the issue often comes back to this very same thing over power in space,” Steptoe said.

The 1917 Houston riot was one of the first major rebellions against police brutality. The uprising brought more awareness to the public about the tense relations between police and Black communities.

Leading Up to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s:

Prior to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Black people in the U.S. had fought as soldiers during many wars including World War II.

“Black soldiers went into World War II still segregated and fought for the nation. I think World War II was kind of a turning point. You cannot fight Nazism and the Final Solution in the Holocaust and come back and segregate and just beat people for the color of their skin,” said Lora Key, a UA Department of History adjunct professor.

After the end of World War II in 1945, the fight for racial equality raged on.

RELATED: March 4 Justice Tucson’s Juneteenth: Institutionalized, history and the present day

In 1954, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education desegregated schools and led to the beginning of other civil rights legislation. However, legislation did not come easy during the Civil Rights Movement and even Brown v. Board of Education had unforeseen setbacks for Black teachers, according to an article from the Online Journal of Rural Research and Policy.

“Roughly 82,000 black teachers were a part of the national teaching force leading up to the 1954 Brown decision. That number would drop by the tens of thousands following the decision,” said Mallory Lutz, author of the Online Journal of Rural Research and Policy article on Brown v. Board of Education.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, a brief overview

Starting in 1961, activists began fighting segregation as the Freedom Riders in an attempt to move legislation forward in integrating the Southern bus lines.

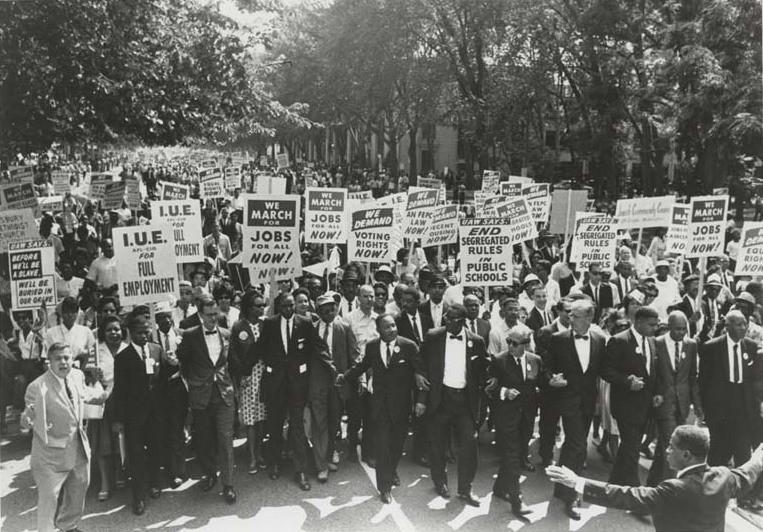

On Aug. 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington D.C. Less than a month later in September 1963, four young Black girls were killed during the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

“In 1964, you get the killing of three civil rights activists: Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner. And that started to make a lot of people fed up. Then in 1965, during the movement for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, at least two non-violent activists were murdered in the Selma area,” Steptoe said. “So in 1965, that becomes a sort of turning point for a lot of the young activists in the movement. They started saying, wait a minute, okay, how many non-violent activists are now being murdered? And thinking enough is enough.”

RELATED: Footage: Black Lives Matter Protest in Long Beach, California May 31, 2020

Tensions between Black and white citizens were high. Black communities began to protest racial injustices by marches, sit-ins and strikes at a local and national level. The protests were successful and national legislation was passed.

In July of 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and an expansion on the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in 1968.

Martin Luther King Jr. maintained “peaceful protests” throughout the Civil Rights Movement. King’s words and legacy have inspired many activists since the movement of the 1960s to stand up for what is right.

“The time is always right to do what is right,” King said in 1964.

The 1992 L.A. Riots: April 29 – May 4, 1992

On March 3, 1991, Rodney King was engaged in a high-speed chase with the Los Angeles Police Department throughout Los Angeles. Once he pulled over, King was forced from his vehicle and was brutally beaten by a group of white LAPD officers while over a dozen officers stood by watching the event unfold.

The beating was filmed by a bystander and spread like wildfire throughout the media.

The beating left King with “skull fractures, broken bones and teeth, and permanent brain damage,” according to NPR.

Over a year later, on April 29, 1992, four LAPD officers were acquitted on charges of beating King. The city erupted in riots in response to the acquittal of the officers and the lack of justice served.

In response to the riots, the local government called for a state of emergency, enforced city-wide curfews, shut down freeways and deployed more than 6,000 National Guard troops to the southern California area, according to the Los Angeles Times.

The Los Angeles riots left 63 dead, more than 2,000 injured and almost 12,000 arrested, according to CNN.

“[The Black community] lost faith in the judicial system and it never really had faith in the jury or judicial system, but this was the final straw,” Key said.

The loss of faith in the judicial system within the Black community is still relevant in current social justice issues.

Trayvon Martin & the beginning of the BLM movement: Feb. 26, 2012- July 13, 2013

On Feb. 26, 2012, Florida native Trayvon Martin, 17, was shot and killed by neighborhood crime watch captain, George Zimmerman, then 28, at the gated community of Retreat at Twin Lakes in Sanford, Florida.

Originally from Miami Gardens, Martin was visiting his father Tracy Martin and fiancee in Sanford and was walking back toward his house after a convenience store run, according to History.com. Upon noticing Martin, Zimmerman called the Sanford police to report suspicious activity and subsequently ignored a police dispatcher’s advice not to engage in contact with Martin.

However, Zimmerman pursued and opened fire on Martin, claiming to have taken action out of self-defense, applying the “Stand-Your-Ground” law, according to History.com. Martin was pronounced dead at the scene. Zimmerman was not arrested at the scene and was later charged with second-degree murder. The case went to triall in June of 2013.

Zimmerman pleaded ‘not guilty’ and was acquitted of all charges on July 13, according to History.com.

RELATED: Pride 2020: A month of legislation, protest and social distancing

As a result of Zimmerman’s acquittal, #BlackLivesMatter was formed.

According to the Black Lives Matter website, the organization was founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Opal Tometi.

“Black Lives Matter Foundation, Inc is a global organization in the US, UK, and Canada whose mission is to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes,” according to the website’s “about” page.

“By combating and countering acts of violence, creating space for Black imagination and innovation, and centering Black joy, we are winning immediate improvements in our lives,” according to the Black Lives Matter website.

Michael Brown & Ferguson Unrest:

On Aug. 9, 2014, Michael Brown, 18, was shot and killed by police officer Darren Wilson in broad daylight in Ferguson, Missouri. Brown and his friend Dorian Johnson left Ferguson Market and Liquor located on West Florissant Ave. and surveillance showed Brown stealing some cigarillos.

Officer Wilson arrived on the scene and told the two men to move to the sidewalk and made a call to the dispatcher that Brown fit the description of the convenience store thief, according to The New York Times.

Wilson fired 12 rounds in total and attested that Brown reached into the vehicle and fought for his gun. However, there are discrepancies in different sources of eyewitness testimony that cannot account for Brown’s movements as to whether or not Brown moved toward or away from Wilson and attempted to surrender, according to The New York Times.

The unrest began later that night on Aug. 9, 2014, through Nov. 24, 2014, when the grand jury in St. Louis County declined to indict Wilson, according to The Guardian.

Around 200 individuals gathered outside the Ferguson Police Department catching wind of the decision which set off civil unrest (protest/riot/uprising) that was fueled by protesters’ outrage over what they called a pattern of police brutality against young black men, according to The New York Times.

This would later be known as the Ferguson Unrest, buildings were set on fire and looting was reported in several businesses. Response from the police that included tear gas and rubber bullets and confrontations between protesters and law enforcement officers continued even after Gov. Jay Nixon deployed the National Guard to help quell the unrest, according to The New York Times.

In St. Louis, protesters swarmed Interstate 44 and blocked all traffic near the neighborhood where another man was shot by police this fall, according to The New York Times.

Thousands of protests and peaceful demonstrations took place around the country to protest the grand jury’s decision regarding the Michael Brown case, according to The New York Times.

Black Lives Matter made two commitments after what happened in Ferguson and St. Louis, “to support the team on the ground in St. Louis and to go back home and do the work there. We understood Ferguson was not an aberration, but in fact, a clear point of reference for what was happening to Black communities everywhere. When it was time for us to leave, inspired by our friends in Ferguson, organizers from 18 different cities went back home and developed Black Lives Matter chapters in their communities and towns — broadening the political will and movement building reach catalyzed by the #BlackLivesMatter project and the work on the ground in Ferguson,” according to their website.

The Black Lives Matter organization and movement did not become as widely recognized as it is now due to the Ferguson Unrest that took place. In the last six years, there have been countless Black lives lost to police brutality and these are the names of some of those individuals: Eric Garner (2014), Tamir Rice (2014), Sandra Bland (2015), Freddie Gray (2015) and Philando Castile (2016).

George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Black Lives Matter today

George Floyd, 46, was arrested and subsequently killed by the Minneapolis Police Department after a convenience store Cup Foods employee called 911 and told the police that Floyd had bought cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill on May 25, according to The New York Times.

Video evidence circulated around social media that Officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, as several other officers watched without intervening, despite Floyd’s cries of “I can’t breathe,” shown in the video taken by Darnella Frazier, a 17-year-old Minneapolis native. The three other officers on the scene were Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao.

Rallies took place Saturday in small towns and suburbs, drawing hundreds of people to communities that in many cases had not yet held protests, as well as in major cities where marches with masked demonstrators toting Black Lives Matters signs have quickly become part of the daily fabric of pandemic life.

The protests spread overseas to Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia.

The Black Lives Matter movement is not just a “moment” but reflects a reality, according to Steptoe.

“So many people, for the first time, realized what Black Lives Matter actually meant. So, whereas five years ago, the term Black Lives Matter scared and confused a lot of people. I think this is a very recent change, I would say and the day that the George Floyd video circulated is the day that this changed,” Steptoe said. “It shows how quickly political discourse can shift. You know, it really just took a video and nationwide protests for people to start at least saying different things.”

As a response to the protests taking place all over the world, Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao were charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder and aiding and abetting second-degree manslaughter. Chauvin was charged with second-degree murder and was awaiting trial, according to CNN.

Black Lives Matter has become a rallying cry in the last couple of months from coast to coast on all forms of social media from Facebook to Twitter to Instagram.

On the eve of March 13, in Louisville, Kentucky, 26-year-old, Breonna Taylor was shot at least eight times in her own apartment. Louisville law enforcement executed a search warrant and used a battering ram to crash into the apartment, according to The New York Times.

RELATED: Exploring Title IX and campus sexual assault through film

The police were investigating two men who they believed were selling drugs out of a house that was far from Taylor’s home. But a judge had also signed a warrant allowing the police to search Taylor’s residence because the police said they believed that one of the two men had used her apartment to receive packages. The judge’s order was a “No-Knock Warrant,” which allowed the police to enter without warning or without identifying themselves as law enforcement, according to the Louisville Courier-Journal.

“The police have said that they returned fire after Taylor’s boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, shot an officer in the leg. He later surrendered and has been charged with the attempted murder of a police officer,” The New York Times reported.

The officers involved in the altercation have not been charged with a crime. June 5 would have been Breonna Taylor’s 27th birthday. As a result, social media exploded with #sayhername to raise awareness to her case.

“Say Her Name attempts to make the death of black women an active part of this conversation, by saying their names like Tanisha Anderson and Atatiana Jefferson, whose similar stories may not have garnered as much national attention,” said Kimberlé Crenshaw, an activist and creator of the hashtag, to ABC on Friday.

On June 9, the Louisville Metro Council voted unanimously to pass Breonna’s Law, which still needs to be approved by the mayor, but it bans any search warrant that does not require police to announce themselves and their purpose at the premises. It requires any Louisville Metro Police Department or Metro law enforcement to knock and wait a minimum of 15 seconds for a response, according to NBC News.

Local communities play and have played an important role in the fight against police brutality, according to Steptoe.

“I think so frequently, the local perspective on things, really shapes who shows up what types of activism people take,” Steptoe said. “For example, in a lot of parts of the country, where you see large populations of people who are of African and Mexican descent, you’re seeing a lot of allyship between those communities, you’re seeing a lot of solidarity around those issues because maybe those communities have had some similar struggles over the past. And in southern Arizona, I’ve heard a lot of people linking Black Lives Matter and the conversation over defunding the police.”

The past 100 years of U.S. history is filled with instances of social uprisings against racially motivated police brutality, and these uprisings continue on each and every day.

“Change is slow. We just gotta stay prayed up, read up and vote, vote, vote,” said Doris Snowden, president of the NAACP Tucson Branch.

Follow the Daily Wildcat on Twitter