Many instructors at the University of Arizona had to completely change how they taught curriculum online because of the pandemic. The UA architecture studio was no exception to this, so students and faculty set out to find a way to make a hands-on class just as valuable with online learning.

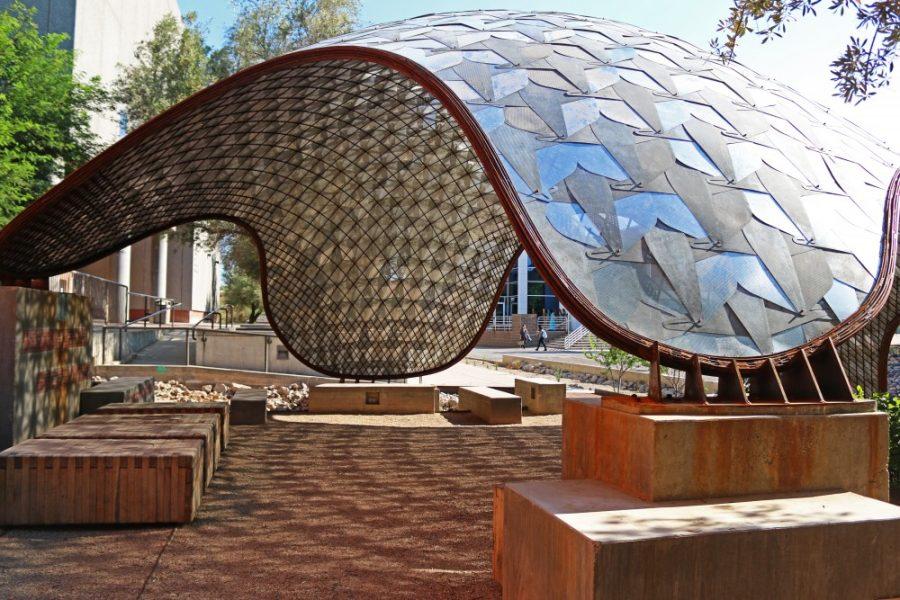

Usually, studio takes place in the UA College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture building, which was open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. CAPLA, as it’s referred to by faculty, staff and students, is filled with students working at every hour of the day in the studios, computer labs and the workshop, practicing a variety of skills to complete a variety of projects from photography and design to woodworking and welding.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States in March, the CAPLA building sits empty and the CAPLA students and faculty are stuck teaching and learning from behind screens. For the architects of the UA, the question became: How do teachers translate one of the most collaborative, hands-on majors into a digital medium?

According to fourth year architecture student Anisa Hermosillo, she and her peers learn just as much from each other as they do from their professors.

“When it comes to our studio course, we rely more on each other than our professors,” Hermosillo said. “Our professors are there for commentary and directing us.”

For Teresa Rosano, a UA architecture professor who teaches site planning and studio, the answer has been to digitally orchestrate interactions that, in person, would happen organically.

“The way [architecture teachers] generally operate, when working physically in studio, is to move from student to student and talk about their projects,” Rosano said.

Due to the openness of studio courses, it’s easy for Rosano to connect students who are working on similar projects or tackling the same problem.

“We’re all in the same space,” Rosano said. “So even though everyone’s concentrating on their own work, you can often hear a conversation that’s happening next to you.”

Digitally, however, the ease of those interactions is almost entirely gone. Both professors and students have tried a variety of methods to replicate the studio environment. Rosano has employed breakout rooms, discussion boards, Google Docs and image-sharing platform Wakelet to help students be able to share their ideas, inspirations and projects with one another.

RELATED: Perspectives on returning to campus

Students, however, don’t just want to collaborate with their peers, but want to be able to collaborate at any time of the day. Hermosillo mentioned how classes adjusted back in March when the UA first closed due to COVID-19.

“We had a Zoom link open at all hours of the day,” Hermosillo said. “Some of my classmates actually jumped onto the Zoom meeting late at night and would share their screens with each other and just get feedback from each other.”

When asked what she missed most about in-person courses, Valerie Rauh, a third-year architecture student, mentioned the feedback of other students.

“Definitely being able to see everyone else’s work. I miss being able to ask [other students] questions and see what they’re doing,” Rauh said. “The motivation of seeing what your peers are doing is gone now.”

While studio is one of the most important parts of architecture coursework that’s been impacted by the pandemic, it isn’t the only one. Another course architecture students take is called site planning, and it involves field trips to locations where students will hypothetically build their buildings.

On these trips, students are able to gain inspiration, take measurements and survey the area. However, students will not be able to go on the field trips this year due to safety restrictions.

To work around this and to give students a taste of professional experience, Rosano has enlisted the help of some of her former students who were able to go on site planning trips to Bisbee and Mt. Lemmon last year.

Rosano’s current site planning students will interview her former students in order to gain the information they need to successfully design buildings for those locations.

“The idea being that it would be similar to a scenario that you might have in practice where you’re working on a project,” Rosano said. “For whatever reason, you may not be able to go to that site and you’re dependent on the local architect to relay all the information, qualitative and quantitative.”

RELATED: Amplified A Cappella voices creativity through performance, new EP

The site planning course isn’t the only way that students are being prepared for a career in architecture. Another silver lining to online learning is how much time students are spending with design software.

For Rauh, spending more time with digital design is good.

“I think it’s really practical knowledge to have,” Rauh said. “You’re going to be spending time with this software for the rest of your career. It’s important knowledge to have if you want to get a job.”

The transition from physical and digital projects to entirely digital projects has, for some students, also revealed the inequities inherent in studying architecture.

“We didn’t have to buy materials and we didn’t have to print out all these test prints,” Hermosillo said. “You save a lot of money … but you get the same quality work. And I think that’s interesting when talking about how architecture can be inclusive.”

Architecture students do have to purchase many of their own materials, but not all students feel that this is any more financially difficult than other majors.

“I don’t see [architecture] as costing more than any other major because we don’t have to buy textbooks,” Rauh said. “Other classes have to buy hundreds of dollars worth of textbooks; we have to buy hundreds of dollars worth of supplies.”

For many students, online learning provided financial relief in regards to materials, but created new burdens at the same time.

“The economic disparity between students often was exacerbated as it pertained to technology,” Rosano said. “There are many students who would just use the school’s computers in the computer lab and then when that became unavailable, all of a sudden they were without an adequate computer.”

In order to help students who are facing this issue, CAPLA set up the CAPLA Student Technology Initiative to fund loaning computers and other technology to students while they complete their coursework from home.

As the semester continues, students and faculty wait to hear about whether or not they’ll be able to safely return to their studios and workshops and continue to test new methods of connecting and collaborating online.

Rosano, who spent the summer asking her students for feedback on their courses to better prepare for the fall, is focusing on being adaptable.

“We’re trying to be very adaptable,” Rosano said. “So that we can see what’s working well and do more of that.”

Follow Katie Beauford on Twitter