PHILADELPHIA — When religion professor Stuart Charme decided to teach a course on the end of the world this semester, he knew he had a compelling hook: the Dec. 21 conclusion of the “Long Count” Mayan calendar that doomsday believers have latched on to as proof that time will end.

But Charme had no idea what the next few months would bring: the cataclysmic Hurricane Sandy, a fiscal cliff some have dubbed “debtmageddon” and an intensifying conflict involving Israel, the place where Christian end-time theorists believe the apocalypse will commence.

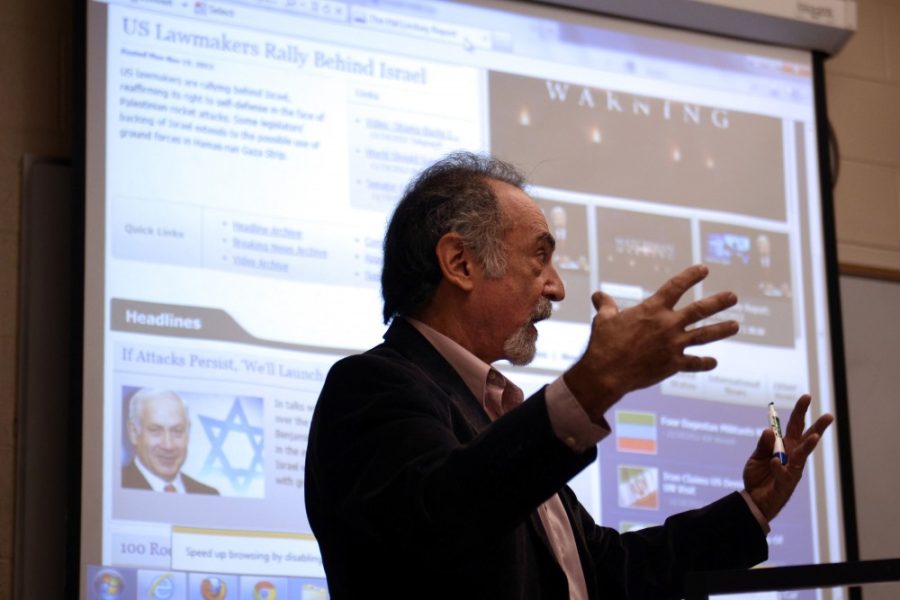

“I didn’t realize this was going to be the most apocalyptic semester that has ever been,” Charme told students at Rutgers-Camden University last week. “If you look at what’s been going on in the world today as we’re down to 30 days and counting, this has been a really good time. And remember that bad is good for the apocalyptically minded.”

And he’s not the only professor offering “end of the world” courses this semester, theoretically the last semester ever.

At Pennsylvania State University’s main campus, Latin American history professor Matthew Restall and his colleague Amara Solari, an art history and anthropology assistant professor, have teamed up on a course, titled simply “The End of the World.”

“We didn’t put 2012 so that we always have the option of teaching the class again,” Restall said, “in case the world doesn’t end.”

Despite the impending doom, students must study, produce projects and take finals.

At Penn State, the final will be given on apocalypse eve, leaving students no choice but to work “right up to the very night the world is supposed to end,” Restall said.

The courses proved wildly popular.

“It filled in two hours,” Restall said of his honors course, which was capped at 35 students. “We had emails for weeks and weeks into the summer from people asking if there was space.”

Students said the course was among their most interesting.

“I find it fascinating to see what people do to comfort themselves,” said Bridgid Robinson, 23, of Haddonfield, N.J., a religion and sociology major at Rutgers-Camden, “because apocalyptic thinking, secular or religious, is all about comfort, or lack thereof.”

Will Wekesa, 25, a psychology and nursing major from Sayreville, N.J., said he had seen all the apocalyptic movies.

“I never heard of a class that could teach that,” he said. “I enjoy it.”

But not one student interviewed — and certainly none of the professors — said he or she actually believed the Dec. 21 expiration date.

The Mayans never predicted the end of time; it’s just a turning point in the calendar, Restall said.

But there’s an apocalyptic anxiety in Western culture, going back many centuries, in which people react to the changes around them by predicting time will end, he said. The Internet has caused that speculation to boom.

Restall noted that over time, there have been hundreds of scheduled doomsdays, and if nothing happens on Dec. 21, “people will immediately begin to move to the next date,” Restall said, or philosophize that Dec. 21 is the beginning of a seven-year period that will bring about the end.