I had no idea at the time that the end of my freshman year of high school would be the last part of my life where I had a normal youth. Over summer break, my father died. Everything was turned upside down.

When school kicked up in the fall, I kept wondering how people would react when I told them, particularly my friends. On my first day, I awkwardly strategized a proper place to mention my new development, I guess because somewhere, I just wanted assurance from someone else that things would turn out alright. That this wasn’t a forever feeling.

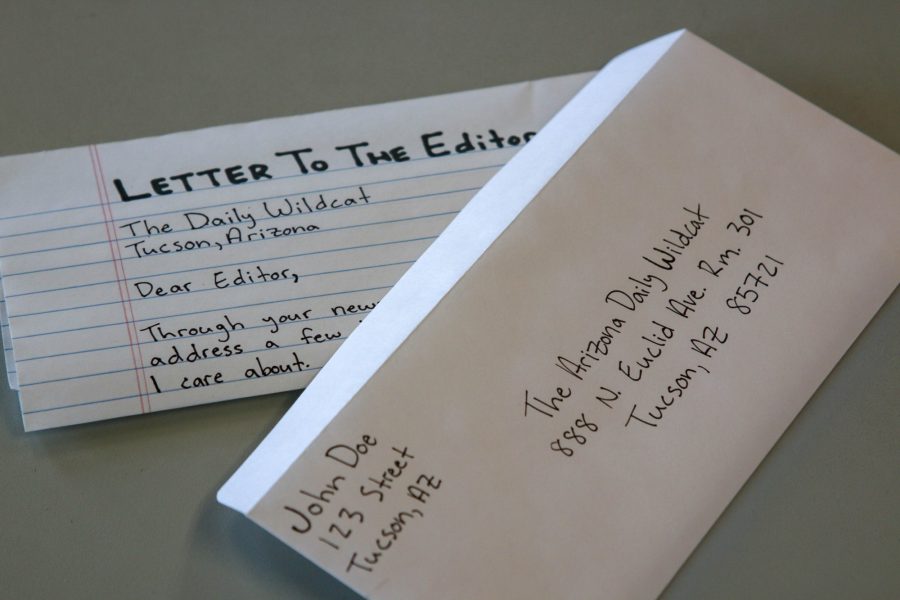

- Ian Stash

When my mother died 2 years ago, I thought that I would find comfort and support among my friends. Instead, I found mostly blank stares, fearful glances and willful ignorance. It was upsetting, to say the least. There I was, at one of the lowest points of my life so far, alone and simply in need of a big, warm hug — but with nobody to give me one and unsure of how to ask for one.

Ironically, my friends seemed more uncomfortable with the death of my mother than I was. I can’t really blame them; a dead parent is not something that most people in their early twenties have had to face. Heck, death in general is not something that people enjoy talking about.

But I wasn’t talking about her death. I was talking about her and I was talking about myself.

I didn’t expect my friends to act as my therapists; I did expect my friends to overcome their own discomfort to empathize with someone who was struggling. All I wanted was to be able to remember my mother with someone.

- Fiona Sievert

Reactions actually varied from person to person quite a bit. Some people patted me on the back and expressed apology, some asked if I was doing alright and others just sort of stared at me while they took in what I just said before talking about something else.

Immediate reactions may have varied, but long term reactions were all the same: it was something that no one ever mentioned again. Some people just didn’t see the point in talking about a story that didn’t affect them, about a man they never knew. Other people just plain forgot that I ever mentioned it to them.

I try not to judge people over it since death is a subject that young people are often unfamiliar with. Nonetheless, this unfamiliarity inadvertently creates an environment where young people struck with grief feel like the most impactful part of their life is something that makes others uncomfortable, something they don’t want to talk about. Or really think about.

- Ian Stash

Nobody is perfect at empathizing correctly. We have all made insensitive remarks in inappropriate situations. Maybe you once asked someone how their partner was doing, only to find out that they had broken up. Mistakes of this nature are awkward, but they also provide openings for genuine connection and empathy — openings which most of us don’t make use of. Instead, this opportunity becomes an awkward silence, a change of topic, a wringing of the hands.

- Fiona Sievert

With time, I took this collective urge to not talk even further. I was afraid to let any of the emotions having to do with grief show, for fear of pushing people away because I made them uncomfortable. In the past, I was a shy and quiet person, but starting here, I started smiling a lot, or making jokes and acting chipper. If I was concerned that someone was smelling any negative emotions from me, I doubled down and drowned it out with an even bigger smile. I talked, even when I had nothing to say. Would somebody overwhelmed with sadness do any of that? I thought it made me feel like nothing could touch me, but was it to convince others that I was alright or was it to convince myself that I didn’t need their help?

- Ian Stash

I have tried countless strategies to spare myself and others an awkward discussion about my dead mother. Ultimately, the only solution I could find was to tackle the problem head-on. I explained to my friends how alienated I felt in a world which seemed to only want me to move on from what had happened — not for my own sake, but for the sake of others. This strategy had varied success, but at least I had taken the first step in casting off self-censorship.

The truth is that it’s not my responsibility alone to sensitize society to the topic of grief and help us all talk about it. As with all conversations, it’s a two-way street. I need to be radically open about my experiences and others need to be radically open to them.

- Fiona Sievert

I think I was afraid. Afraid that touching a taboo subject would make other people nervous or uncomfortable and would only isolate me at a time where isolation would harm me the most. I guess I used the happy faces not just to cope, but to blend in and avoid touching what I had grown to believe was a third rail.

With that in mind, I sometimes ask myself how I would react if I was in their shoes. One would hope that you could be a supportive and compassionate friend in their darkest hour, but if you don’t have the emotional knowledge or experience, it’s difficult to find a way to be what your person needs you to be. After all, what your person really needs is probably not clear even to them.

- Ian Stash

It’s not easy to become comfortable with the uncomfortable, but avoidance will get us nowhere. None of us, grievers and not-yet-grievers alike, can allow our own discomfort to serve as an excuse for remaining silent about this topic.

As with most things, not talking about it won’t make it go away. Grief will, unfortunately, touch all of us one day. A society that would rather not talk about grief is also one that will leave individuals to struggle all the more when they inevitably have to face some form of it on their own.

Solving this means facing death and saying the word out loud and demystifying the topic as a whole. Children need to learn about death just like they need to learn about life. Telling kids that their dead relative simply went on a really long trip — or moved away or some other story — only confuses and obfuscates, and subsequently reinforces the idea that death is somehow less real or that it should not be talked about.

On a more individual level, if you know someone struggling with grief, don’t assume that they’re as collected as meets the eye. Reach out, ask them how it feels or just listen to their stories about a lost loved one. Be the one that helps them through a tough time instead of just another person who didn’t want to talk about it.

And if you yourself are grieving, do your best to face the discomfort of others head on. To change the dominant culture, one must challenge it to evolve, even when it’s difficult. By remaining silent about our grief, we are also contributing to maintaining a troublesome status quo, not to mention the damage to your own mental health.

It is only through radical openness and honesty that we can lessen the toll that death takes on us all.

Follow the Daily Wildcat on Instagram and Twitter/X

Fiona Sievert is an undergraduate at the University of Arizona double majoring in Anthropology and East Asian Studies with a minor in German Studies. She loves languages, wearing funky outfits, and (occasionally) being a dirtbag in the great outdoors!

Ian Stash is a junior studying Journalism at the University of Arizona. In his free time, he loves video games and chilling with his cats.