MIAMI — Not a single drop of the massive BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico touched the land-locked city of Homestead, Fla., or the Keys peninsula to the south.

But a Homestead businessman saw the April 2010 oil rig explosion and subsequent environmental disaster as an opportunity to cash in, authorities say. Jean Mari Lindor filed about $15 million in BP damage claims for himself and others for wages purportedly lost due to the spill’s economic hit on the region’s tourism and fishing industry.

Lindor submitted as many as 700 suspicious claims, mostly for low-income workers who each paid him a processing fee of $300, a prosecutor said in federal court last week. As a result, Lindor and the other South Florida claimants were paid about $3 million from the Gulf Coast Claims Facility, which was established by BP after the protracted Deepwater Horizon spill.

Lindor, arrested earlier this month, is among nearly 110 people nationwide who have been charged with defrauding the BP oil-spill fund program over the past two years, according to the Department of Justice. The majority of the offenders have been charged in Alabama.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas Watts-Fitzgerald said Lindor filed “fraudulent documents” as he allegedly fleeced the $20 billion compensation program set up by BP for oil spill victims in an agreement with the Obama administration.

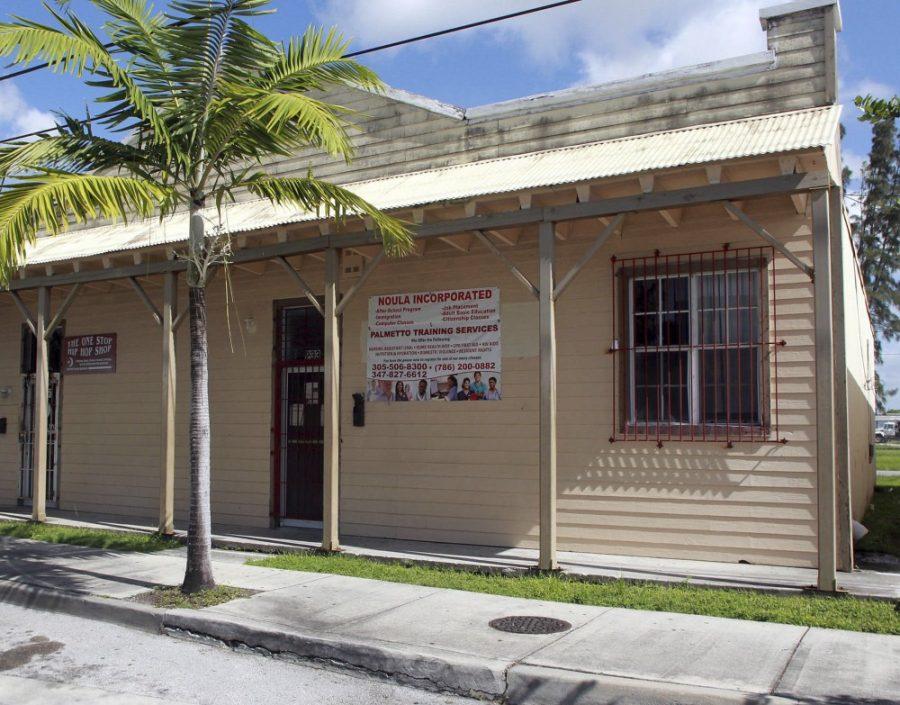

The prosecutor said Lindor, 41, committed “multiple frauds” as he engineered an “affinity crime,” noting the majority of people who filed the loss claims through his business Noula, Inc., were, like him, of Haitian descent and lived in South Florida. In court, Watts-Fitzgerald also cast doubt about the general validity of their claims, because they lived so far away from the spill off the Gulf Coast.

Under the BP fund program, any person or business in the United States or foreign countries could file compensation claims for lost wages or other economic damage caused by the disaster, as long as they submitted proof, including legitimate documentation, such as income tax returns and other financial records.

Lindor’s Miami attorney, Joel DeFabio, said that he and his client “looked forward to defending the case.”

“It seems that the allegations in this case are on par with BP’s continued representation that its rigs were safe,” DeFabio said, adding that he was “skeptical of the government’s claim that the oil spill had no effect on people’s wages in the Keys area.”

In other South Florida criminal cases, offenders have been accused of stealing the identities of others to file false claims with the BP fund.

Among them: A Miami federal jury in June convicted Joseph Harvey and Anja Karin Kannell of using the “assumed identities” of actual people living in the Florida Panhandle, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama to file fraudulent claims for millions of dollars in lost wages stemming from the spill. They collected about $700,000 in BP payments, authorities say. The Delray Beach couple face sentencing Thursday.

The administrator of the Gulf Coast Claims Facility, which was established in August 2010 and dissolved in March of this year, said that fraud was an inevitable part of applications seeking BP funds.

“Over the years, I’ve realized that anytime you establish a very generous public compensation program, it will trigger a certain amount of fraudulent activity,” said Kenneth Feinberg, a Washington, D.C., attorney who was appointed by BP and the White House to serve as the fund’s claims administrator.

Rattling off statistics, Feinberg noted that the claims facility found about 18,000 individual applications that “satisfied our suspicions of fraud.” After the facility’s investigators reviewed them, Feinberg said he referred about 4,000 of those applications to the Justice Department for criminal review because they included “doctored” paperwork.

He said that overall the amount of fraud in “absolute terms” was “substantial,” but in “relative terms” it was “modest.”

The Gulf Coast Claims Facility received about 1.1 million claims from all 50 U.S. states and 35 foreign countries. Overall, it approved more than one-third of those claims, totaling $6.5 billion in payouts to 226,000 claimants. The majority of applications were denied for lack of valid documentation, and a fraction for fraud.

“There’s a far cry from gaming the system and pushing the boundaries of the (claims process) to doctoring tax returns and adding zeros,” said Feinberg, who also served as the administrator for the 9/11 victims’ compensation fund and the government’s TARP bailout for banks.

Asked how some suspected criminals were able to bilk the BP fund program, he said: “You can’t catch everybody. Inevitably in a program like the GCCF, mistakes are made and certain fraudulent applications are paid.”

Lindor’s alleged scheme was run out of his Homestead company Noula, which was infiltrated as part of an FBI undercover investigation.

According to a court affidavit, the probe started when the FBI received a tip last September that Lindor was breaking the law under the cover of his business, which “purported to provide immigration services to immigrants in the area.”

Then, the FBI obtained a “complaint report” that had been written in early 2011 by someone claiming to be associated with the Ocean Reef Club in Key Largo. The complainant’s email said that more than 20 employees were in on Lindor’s scheme, including a housekeeper who made $12,000 a year and who, after submitting “fictitious information,” received $19,000 from the BP fund.

“Many people are Haitian and Hispanic, and they are being told to be quiet and take the money,” said the tipster, who wanted his identity protected.

An Ocean Reef Club spokesperson declined to comment.

FBI agents, assisted by the U.S. Postal Inspection Service and Secret Service, discovered that other claims for lost wages were filed through Lindor’s business by 15 employees at the Island Grill in Islamorada.

The investigation also uncovered that Lindor himself filed a claim for BP funds in November 2010, in which he asserted that his work hours were “drastically reduced” at the Coalition of Florida Farm Workers Organizations “as a result of a slowdown in business due to the oil spill,” according to the FBI affidavit.

Lindor, who had worked for the farm cooperative from 2003 to 2009, said in his application that he made $22,700 in 2010. But investigators found that he had no reported earnings from the cooperative for that year.

Lindor, a permanent U.S. resident who has lived in South Florida for 20 years, has been charged by a federal criminal complaint accusing him of filing a fraudulent BP claim for himself and of illegally trying to obtain U.S. citizenship. But a pending indictment is likely to add the hundreds of allegedly false claims he filed on behalf of other people.

On Aug. 14, U.S. Magistrate Judge Patrick White denied a request by Lindor’s attorney for a nominal bond, after the prosecutor pointed out that the defendant’s uncle and others who were willing to put up his bail received money from his alleged BP claims scheme.

“It’s an indication of how incestuous this is,” the prosecutor, Watts-Fitzgerald, told the judge.

White found that Lindor would be a “flight risk” to his native Haiti, keeping him behind bars before trial.

“Fraud seems to be a lifestyle (for him),” the judge said.