KABUL — When he saw the flowing blood, Mohammed Anwar at first thought his son was dead. Five-year-old Muqadas had been shot in the head in June during a firefight between U.S. forces and Taliban insurgents in eastern Afghanistan.

But Anwar’s quick response not only saved his son’s life, it also secured modern medical treatment that has allowed Muqadas to resume a normal life.

Thousands of Afghan civilians are killed or maimed each year in warfare, and most are doomed to rudimentary medical care in this impoverished country. In Muqadas’ case, there was no hospital or clinic near his home, so Anwar drove to a U.S. military base about a mile from his remote village in Lowgar province. When gate guards saw his critically wounded son, they rushed him inside, where U.S. Army medics worked to stop the bleeding.

Within minutes, Anwar recalled, he and his son were placed aboard a medevac helicopter for a 10-minute flight to the American medical facility at Bagram air base near Kabul. There, emergency medical treatment saved the boy’s life.

The U.S. military specializes in treating serious wounds, including head and brain injuries caused by bullets or shrapnel. The Bagram hospital is staffed by specialists such as neurosurgeons, and has sophisticated medical equipment not available in Afghan hospitals.

Muqadas emerged from an eight-day coma partially paralyzed and with severe neurological damage. He was transferred to a medical program run by the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Treated by Western and Afghan doctors and nurses, the boy has since learned to walk and talk normally.

Since December 2011, USAID’s Afghan Civilian Assistance Program has provided medical treatment for 180 Afghan patients. That’s a tiny fraction of the tens of thousands of Afghans wounded in fighting or by mines or roadside bombs since 2001, but for Muqadas, the care probably saved him from lifelong paralysis.

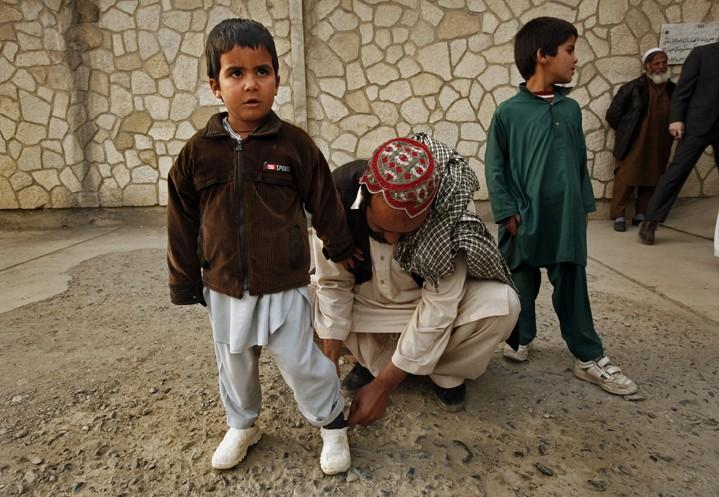

“He couldn’t walk; he could hardly open his eyes,” Anwar said in a Kabul civilian hospital ward where his son is undergoing outpatient physical therapy. He gestured toward the boy, who sat quietly in his lap. “And look at him now.”

Muqadas whispered to his father and smiled shyly. A plump boy with cropped black hair and a round face, he’s active and energetic and plays with other children. He is undergoing therapy for partial paralysis in his left foot, which causes a slight limp.

Three months ago, the boy was confined to a hospital bed. He had difficulty speaking, eating and drinking.

“He lay on the bed like a piece of meat,” said Dr. Abdul Shakur Furmoli, who has helped direct Muqadas’ care under the USAID program. “Now this child is 99 percent returned to his normal life. He has a small limp — that’s all — and we’re working to correct that.”

The assistance program, known as ACAP, is designed to treat Afghans wounded during combat between U.S. and coalition forces and insurgents, regardless of which side is directly responsible.

(In its latest casualty report, the United Nations said that in 2011, at least 3,021 Afghans were killed and 4,507 wounded in war-related incidents, with insurgents responsible for 77 percent of the deaths.)

In Muqadas’ case, American officials at the ACAP program said they were unable to determine which side fired the bullet that struck the boy. Anwar said he didn’t know; he said his son was wounded after Taliban fighters fired on two U.S. helicopters.

The bullet remains embedded in the boy’s skull, left there by doctors at Bagram. Because Muqadas’ brain is healing, Furmoli said, there is no medical reason to risk surgery to remove the projectile.