A mechanical engineering graduate student — who is remaining anonymous for his safety — from Tripoli, said his grades began to dip as the revolution in Libya picked up speed.

Most of his family took part in the demonstrations, and two of his brothers were shot, one of which could not go the hospital out of fear of being killed by ruler Moammar Gadhafi’s mercenaries when he got there.

Both of the student’s brothers survived, and he said his professors were understanding and supportive. He plans on returning to Libya and using his degree to rebuild his country.

“Almost 30 years and I never tasted freedom in my country,” he said. “I need to go back.”

After more than 40 years as ruler of Libya, Gadhafi has been ousted as a result of the Libyan revolution and civil war that began in mid-February.

More than 6.5 million people populate the oil-rich North African country that had an unemployment rate of 30 percent in 2004, according to estimates in the CIA World Factbook. As of 2010, the country ranked 84th of 227 countries in gross domestic product per capita at $14,000.

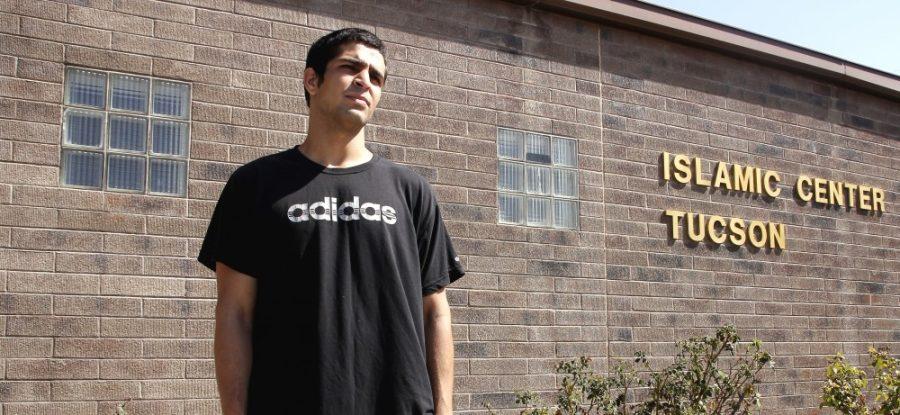

The inequality is impossible to ignore and especially visible in the rundown structures millions are forced to live in, said Aman Tekbali, a history senior, Libyan and Muslim who has gone back to Libya about a dozen times, most recently last January.

Tekbali said none of his family members were hurt during the revolution, but his house was bombed. He said his uncle was imprisoned for 17 years for being a political dissident and never received a trial.

Gadhafi’s grip on free speech has been in place since the beginning of his reign when he began hanging students in the 1970s for voicing discontent with the regime, Tekbali said. Pictures of Gadhafi are everywhere and sometimes he would broadcast a picture of his foot on all the TV stations for an entire day, he added.

“It’s about breaking minds,” Tekbali said. “We’re talking about human beings. And to the question of ‘Why should I care?’ I’d respond with another question. Why shouldn’t you? You should care about human struggles everywhere.”

Tekbali said several of his friends went overseas to join the revolution and fight alongside the rebels. Initially, he wanted to go too, he said.

“I don’t care about dying, especially for that cause,” he said. “But I have bills, car payments and debt over my head that I can’t abandon and force someone else to pay,” he said.

Tekbali said Gadhafi should be tried in a Libyan court and hanged.

As long as Gadhafi remains at large, he could play an outlaw role and attempt to destabilize the country with guerilla raids and other disruptions, said Leila Hudson, associate professor of Middle East history and anthropology and director of the Southwest Initiative for the Study of Middle East Conflicts.

“It took a long time to find Saddam (Hussein) and Osama (bin Laden),” she said. “Gadhafi said in a statement that his retreat from Tripoli was tactical.”

Chris Adams, a political science senior, said he has been monitoring the revolution because of its potential impact on the oil industry and the United States’ European allies. He said the American media has not done a good job of investigating the rebels’ motives, especially religious ones, to gauge how much of a role Islam will play in the new government.

“We just see these people wanting to overthrow Gadhafi,” Adams said. “There’s been no inspection into all the groups that are involved. As a nonreligious person, I wouldn’t be in favor of Shariah.”

Shariah is an Arabic word meaning “legislation” that is derived from the Quran and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad. According to Sunni Islam, the six principles of Shariah are the protection of life, family, education, religion, property and human dignity.

“Of course I want Shariah in Libya,” Tekbali said. “It’s used as a dirty word in America because people don’t know what it means or they lie about it. A school takes pork off the menu and it must be a Muslim plot to take over the cafeteria. It’s insane.”

Tekbali said he would like to see Shariah implemented for family law and have a classical liberal government to handle federal issues.

“The extent to which the revolution was motivated by Islamic movements is still pretty unclear to the outside world,” Hudson said. “The American tendency to jump the gun on these things probably does more harm than good. Putting together a functioning government after decades of arbitrary authoritarian rule is going to be messy, drawn out and friction filed. But that’s what popular sovereignty and democracy look like.”

Tekbali said he already knows what he plans on doing the next time he is in Libya, which could be next summer.

“Being free and talking politics in public,” he said. “I’m going to enjoy it.”