Through researching human thought processes, a doctoral candidate has become every test-taker’s best friend by developing a way to predict when a question will be answered incorrectly.

Federico Cirett, a doctoral candidate in computer science, began working with technology that can measure brain activity as a way to find consistencies in the mind’s thought processes. After reviewing his data closely, he discovered he was able to tell when a person would answer a math question incorrectly.

“I was doing data mining, which is when you are looking for patterns in the data made by the brain, when I noticed this,” Cirett said. “My first reaction was like, ‘Wow, we might have something here.’”

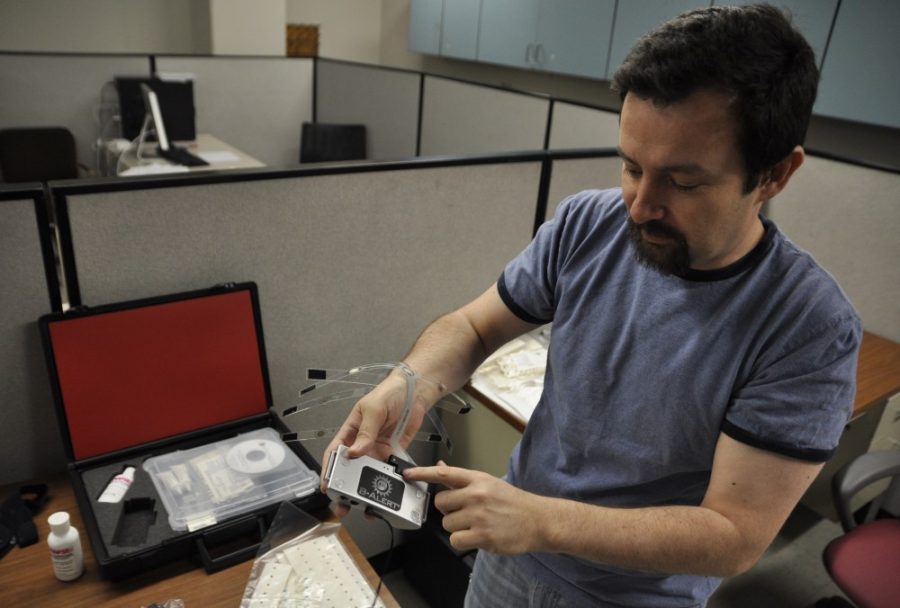

Through National Science Foundation grant funds, Cirett began testing students using electroencephalography, also known as EEG, where a device is placed on the participant’s head that can measure brainwaves up to 250 times per second. This is the same type of technology the military has used to help measure brain activity in soldiers who have been awake for more than 24 hours or have jobs where they can be easily distracted, Cirett said.

“This technology has been used to test if a person is attentive, engaged, distracted or drowsy,” Cirett said. “Testing with an EEG is usually long as well.”

During the tests, participants were given eight math questions that range from basic mathematics to content from the SATs. Cirett looked at the last 30 seconds of a participant’s brain activity to determine if they would answer a question wrong, and the his observations have an 80 percent success rate.

“There are various signals the EEG gave us, but the two we look at are engagement and workload,” Cirett said. “Engagement happens when you are visually taking something in, and workload when there is cognitive activity, or processing happening in the brain.”

Carole Beal, a professor in the School of Information: Science, Technology, and Art, has advised Cirett in his research and said she is happy with the progress he has made in the filed. His research will show people why he deserves to get his doctorate, she said.

“I think any doctoral program is a long road,” Beal said. “And he has done really well. You have to be really smart and really determined to want to do this kind of work.”

Cirett said he hopes his study will help educators determine how to better prepare students for tests and lessons in the future. He suggested tutoring as an option for people in the study who were uncomfortable applying the material they had just learned.

“When someone was answering a problem, I could tell within the first 30 seconds if a kid was struggling,” Cirett said. “It is not that we are not getting it, but that they might need more time to understand it completely.”