Thirteen-year-old Brian Jeffries sat next to the radio listening to Seattle Supersonics games. Jeffries did his best to catch all 82 games and listen to the legendary voice of longtime Supersonics play-by-play man Bob Blackburn.

“It fascinated me that he could be anywhere in the country broadcasting this game and I could close my eyes and I was [transported to] where he was,” Jeffries said. “He was so descriptive of the game. I just had the bug to do that.”

Jeffries tried his hand at radio. At 16, he earned the spot to do his first commercial for the Bank of Tacoma. It helped, of course, that his father was the president of the bank at the time.

“I didn’t get paid a thing,” Jeffries said, laughing.

He took that passion into his first radio job in Yakima, Washington. In a town of just 50,000 people, Jeffries was the morning rock-and-roll disc jockey, the newsman in the afternoon and even did play-by-play for local high school games.

“I had a teacher who told his students go on the two-year plan,” Jeffries said. “Get your first job, stay there for two years no matter what and then look for your next job.”

Boise, Idaho would be his next destination, a bigger market of 200,000. Two years later, he came to Tucson and earned a job at a new local radio station KMGX in 1980. In the span of six years, the UA lost four play-by-play announcers. Each time Jeffries applied, he was turned down.

“I got turned down three times,” Jeffries said. “Then, they finally gave it to me. I remember sitting in the office and the general manager on the other side of the desk looked at me and said, ‘Brian, I am sick and tired of you coming in and applying for this job. So you can have it.’”

One of the times he was turned down, the job was handed to Ray Scott, who had retired to Tucson. Scott had previously been the voice of the Green Bay Packers and was the voice of Super Bowl I and II.

“It turned out to be the greatest blessing I could have asked for,” Jeffries said. “He was a legend in the broadcasting business. He taught me more than I could ever tell you.”

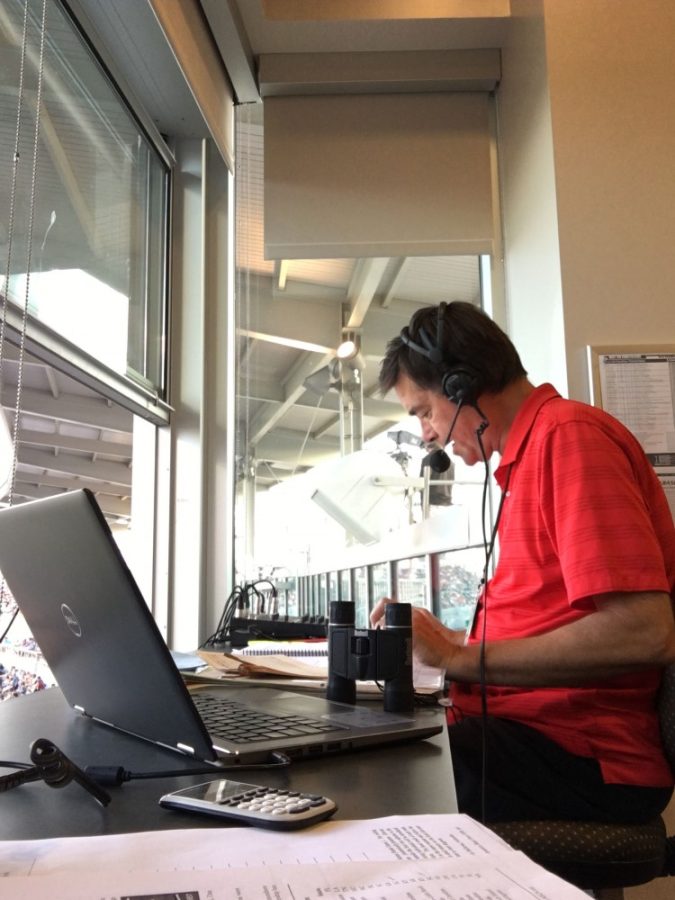

In the fall of 1987, Jeffries landed his dream job and became the voice of the Arizona Wildcats that the Tucson community has grown to love. It would be five years before he was comfortable with his radio identity.

“As a radio announcer, you are painting the picture,” Jeffries said. “There is no camera. There is no stat box on the screen. You have to provide all of that. That’s why I love radio.”

While some might try to imitate announcers like Vin Scully, Jeffries learned first-hand that you have to be you.

“One thing that I learned is to be yourself,” Jeffries said. “Like anybody else, you grow up listening to all these other voices and want to be like them. My philosophy is you will never make it if you do that. You need to be you.”

With listeners constantly tuning in and out of the game, Jeffries found a way to keep them connected. He calls it time-score-ball. How much time is on the clock? What’s the score? Where’s the ball?

“Those are three basics,” Jeffries said. “You don’t know whether people are tuning in or tuning out, or how close they are listening.”

Jeffries quickly became a staple in the athletics department and greater Tucson community.

His wife, a 1986 UA grad, has worked at the UA for 20 years. His daughter, a current junior at the UA, would only consider the school in Tucson. His son will be an incoming freshman next year, hoping to pursue a business degree.

“The biggest reason I love working here is the people,” Jeffries said. “It’s great that the teams win for the most part, which makes my job more fun. Great credit goes to the school for always hiring quality people.”

Jeffries has seen it all for Arizona men’s basketball. He was present for the 1997 National Championship victory. He was there for the first trip to the Final Four in March of 1988.

“That was a feeling … you still get chills,” Jeffries said. “There’s only that one time, the first time you ever get to go to the Final Four. 1997, I’ll never forget, too.”

At the same time, Jeffries has formed relationships with coaches and still interviews them following a loss.

“You have to earn the trust of the players and coaches,” Jeffries said. “That can happen quickly or it can take some time. It usually takes a season. I try to build that trust that I’m on their side.”

While he doesn’t like to show bias, Jeffries does have his fair share of favorite Wildcats over the years.

Steve Kerr comes to the mix first for everything that he endured as a player during school. Jeffries recalled the ASU taunting of Kerr following his father’s assassination in Beirut in 1984.

“I hurt for him, I thought it was unbelievable,” Jeffries said. “From what I could tell, nobody tried to stop it. I just felt so bad for him. I would love to find all those students and see them today and find out what became of them, ask them if they regret it.”

Jeffries also was reminded of the 1986 National Championship baseball team. During postseason play when the team practiced at a high school, he would chase balls for the team.

“I couldn’t throw more than 20 yards,” Jeffries said. “Outfielder Dave Shermet actually taught me how to throw the ball. I was incorrectly throwing the ball. Those were great memories.”

With the hustle and bustle of the sports industry, there are hardly any breaks.

“I kind of look at this job like I’m still in school,” Jeffries said. “Nine months out of the year, I work my rear end off. I work six or seven days a week for nine months.”

Right before the Pac-12 Networks launched, there was a three-year span where Arizona Athletics produced the local television for Arizona basketball and football.

“I was on vacation 8,000 feet up in the Rocky Mountains with a fishing pole in my hand when I got a call from my boss,” Jeffries said. “He said we are taking over TV production. You have six weeks. It was the most stressful three years of my life.”

With live broadcasts, Jeffries knows he makes mistakes. It doesn’t mean he doesn’t hope to chase perfection.

“I hope every game I broadcast is better than the last one,” Jeffries said. “I never want to be satisfied. I will always make mistakes.”

Early on in his career, Jeffries thought his career might be finished. He told Scott he didn’t think he could do this anymore because of how many mistakes he made.

“In this voice from God, he said, ‘Bryan, I’ve been broadcasting for 75 years and I’ve never called a perfect game,’” Jeffries said.

Jeffries still hasn’t.

Follow Matt Wall on Twitter