The University of Arizona MycoCats organization regularly pack bags, but not for any vacation.

These bags are full of what the mushroom community refers to as substrate: corn or straw, mesquite pods, mesquite wood, palo verde wood, cotton seed and alder wood. The purpose of these bags is to eventually create inoculation environments for mushrooms to grow.

There is a MycoCats student club, made up of students who are interested in gourmet mushroom cultivation, as well as a local organization in Tucson by the same name, which is run out of professor of plant sciences Barry Pryor’s lab.

The MycoCats organization recycle and grow mushrooms with a focus on sustainability, as well as make spawn and fruiting bags to sell to local growers. According to Pryor, the funds from these sales support two to three student employee’s half time at the lab.

The MycoCats organization works with the Arizona Mushroom Growers Association, commercial mushroom growers who advocate educating, participating and engaging students as well as the public in how to be efficient mushroom growers.

“Mushroom cultivation can be used for waste reduction and sustainability by diverting waste from landfills,” said Ben Nach, president of the MycoCats student club and a senior majoring in biochemistry.

According to the AZMGA website, inoculation is when fungi cultures are introduced to substrates which make spawn, and begin the process of growing mushrooms.

The main processes of creating environments for mushrooms to grow is making a culture, making a spawn and making a fruiting bag, according to Pryor, who is also director of the Arizona Mushroom Growers Association.

“Mushrooms are pretty efficient in terms of water usage — more than a tomato, or lettuce,” Pryor said. “We use much less water to grow mushrooms.”

The MycoCats student club conducts studies and research in optimizing mushroom production, and, according to Nach, has done projects in the past to show how mushrooms can be grown on all sorts of things that would otherwise end up in a landfill, like soiled pizza boxes, lawn clippings and mesquite pods.

“We’ll do experiments on which woods work the best,” Pryor said. “Palo verde wood works much better than mesquite wood.”

The MycoCats organization is run by Pryor and intern students, and works with the MycoCats club.

“Mushrooms that the MycoCats club grow are from commercial sources,” Pryor said. “The MycoCats organization supplies the club with spawn for their bags.”

The whole process to prepare straw substrate starts by shredding and soaking the straw in water for 24 hours, according to the AZMGA website.

After the bags are filled with the substrate they are then autoclaved, or sterilized with steam. The autoclave process is similar to a large pressure cooker, according to Pryor.

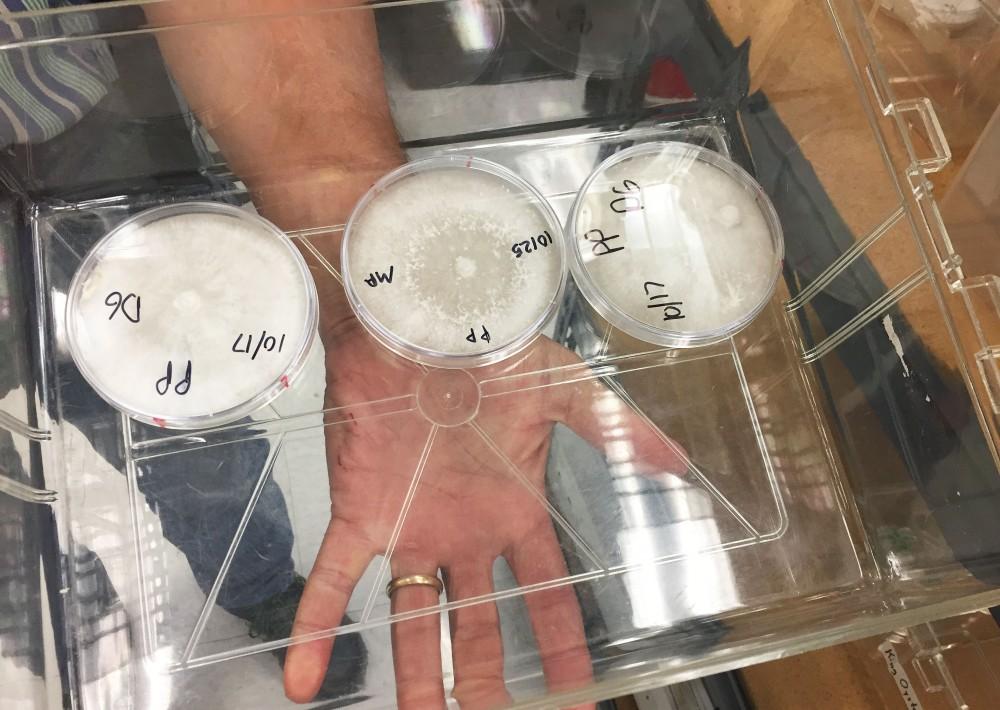

Students also maintain fungal cultures in petri dishes at the Pryor lab, and prepare the spawn to be inoculated.

“Both the spawn and the substrate need to be sterilized before we inoculate them with our fungus, in order to destroy any of the resident fungi and bacteria that is on these things,” Pryor said. “We want to destroy the resident organisms so that our fungus does not have anything to compete with.”

The Pryor lab populates petri dishes with cultures of fungi. Then, according to Pryor, fungi-colonized spawn is bagged and brought to a separate room to inoculate the pre-soaked bags.

The end result is a bag filled with the fungi. According to Pryor, to have a good result, the bags of spawn cannot be packed too tightly.

The bag of corn spawn usually takes 10 days to colonize, and the straw spawn takes two weeks, according to Pryor. Soon after that time period, mushrooms will grow and break through the bag, proving the success of the growing preparation.

Some of the bags that are packed by the MycoCats student club are sold to commercial growers to help them develop their mushroom programs.

“After the mushrooms are harvested, the “roots” of the mushroom, called mycelium, remain, which can then be used as a garden amendment for soil,” Nach said. “Not only do mushrooms make a delicious meal, they can also prevent landfill waste and improve your garden.”

The MycoCats student club is currently partnered with Tucson Village Farms to put the mushrooms that they grow into the farm’s mushroom houses for further growing and to be sold.

“Most mushrooms are grown in a controlled environment facility, ” Pryor said. “Even in Pennsylvania, the top state to grow mushrooms, [the mushrooms] are grown in houses to maintain humidity, temperature and CO2 content very precisely.”

According to Pryor, the MycoCats student club has started other programs to utilize their spent substrate by adding the material directly to a garden, which can also be used for insect food.

The Pryor lab graduate student Lauren Jackson used spent substrate from the MycoCats student club mushroom-growing process and added it to cylinders for filtering rain runoff from streets or from urban areas to protect watersheds with natural methods.

The filtering process using natural methods is called bioremediation. According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s A Citizen’s Guide to Bioremediation, bioremediation is the use of microbes to clean up contaminated soil and groundwater.

It works by stimulating the growth of certain microbes that use contaminants as a source of food and energy.

According to Pryor, mushrooms are able break down carcinogens such as aflatoxin.

“We found that you can grow mushrooms from heavily contaminated mesquite pods or corn, Pryor said. “And the mushrooms and product you [have] grown the mushrooms from become aflatoxin free itself.”

The MycoCats organization is looking at decontaminating toxins and petroleum products that wash off roads and yards before they go into watersheds.

The methods of decontamination the Pryor lab is researching to potentially test are using artificial berms, or erosion blockers, packed with spent corn or straw substrate.

“We are looking at the same decontaminating process through mushrooms to filter the water that contains certain pharmaceuticals in sewage discharged in Tucson,” Pryor said.

According to Pryor, mushrooms can decontaminate toxins with two important groups of secreted enzymes: peroxidases and laccases. These two enzymes are responsible for breaking things down around them.

“Mushrooms are the most important decomposers on Earth,” Pryor said.

Through the Arizona Mushroom Growers Association, the MycoCats organization produce workshops for mushroom growing throughout the state. The lecture series are posted on the AZMGA website.

Follow Olivia Jones on Twitter