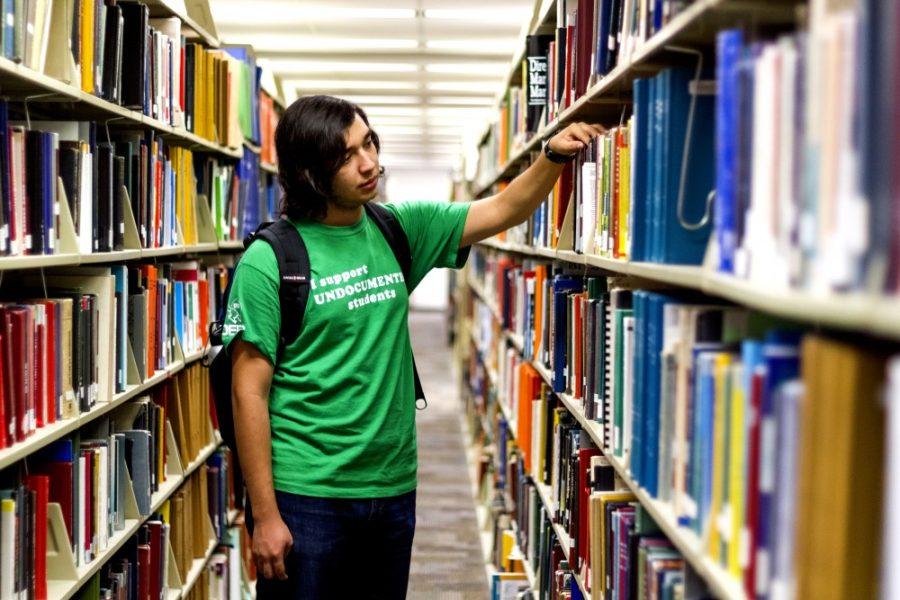

Guillermo Huerta’s first week at the UA was, he said, “kind of terrifying.” He spent the time between classes sitting outside.

“I didn’t know what to do with that time,” he explained, laughing, “so I’d just go sit on a random bench for three hours.”

The problem was exacerbated by the bus strike, which forced Huerta to accept rides that got him to campus before 8 a.m. every day, and a class schedule full of long gaps.

“I didn’t apply until June,” he said, so most classes were already full when it came time to choose his schedule.

Huerta applied so late because he is an undocumented immigrant with a work permit and relief from deportation under President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. He and his mother came to the United States from Mexico when Huerta was only 5 years old.

Until May, when the Arizona Board of Regents voted to allow DACA students to pay in-state tuition, attending the UA was not a possibility for Huerta. After May, he was rushed to find a way to afford the $5,861.94 in tuition and fees he would owe for his first semester.

“What we’re doing is my mom’s boyfriend is lending us money,” he said. “I just have to pay him back in installments.”

As a DACA student, even though he is now eligible for the 66 percent discount afforded to Arizona residents at the UA, Huerta is not eligible for institutional, state or federal financial aid and subsidized loans. There are a limited number of private scholarships available to undocumented students, and Huerta applied for one, but, he said, “I didn’t get it.”

Still, Huerta spent three years at Pima Community College, and he was ready to move on to the university level. So he’s here now, even though he is unsure how he will find the money to continue in future semesters.

Huerta is a pre-major in both computer science and neuroscience and cognitive science. Given the extensive requirements of both majors, he thinks it will take him another three years at the university level to graduate. After that, he’d like to continue all the way to his Ph.D.

“I want to study artificial intelligence,” he said.

This dream is possible for the first time in almost a decade.

In 2006, Arizona citizens voted to pass Proposition 300, banning students without lawful presence from “classification as an in-state student” and from receiving “financial assistance that is subsidized or paid […] with state monies.”

Dean Martin, a former Arizona state senator who wrote the legislation that placed Proposition 300 on the ballot, argued that the state shouldn’t educate undocumented immigrants who couldn’t legally work.

“If you’re not here legally, the state shouldn’t be spending resources that it doesn’t have to subsidize your tuition …” he told the Arizona Capitol Times in 2011. “You’re not going to be able to use that degree to do anything anyway.”

But one year later, that ceased to be true.

In June of 2012, President Obama announced an executive order creating the DACA program, which grants certain undocumented immigrants lawful presence and a temporary work permit.

In order to qualify, a young person must have been brought to the United States before their 16th birthday, have graduated or be enrolled in high school or a GED program and have lived here continuously between 2007 and 2012.

Now, DACA students like Huerta can use their degrees to get jobs, contrary to former state senator Martin’s fears. And with their new classification as lawfully present under federal law, they can no longer be denied in-state tuition under Proposition 300.

At least, that was Maricopa Community Colleges’ understanding when its board voted in 2012 to charge DACA students in-state tuition. PCC followed suit in February of 2013.

Then-Attorney General Tom Horne understood the implications of DACA differently, and he sued MCC.

On May 5, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Arthur Anderson ruled that the state couldn’t have a definition of “lawfully present” that was different from the federal government’s. The MCC tuition policy was upheld.

It was the second major case about the implications of DACA for state law that the state had lost. The first came in December of last year, when a federal judge ruled that the state had to issue drivers’ licenses to residents with DACA.

This was the legal landscape facing the Board of Regents when they met on May 7, two days after the ruling. They voted unanimously to immediately reclassify DACA students as in-state students.

And that’s how Huerta ended up at the UA.

Twin brothers Dario and Danilo Andrade Mendoza had a similar journey to the UA. Like Huerta, they, too, grew up in Tucson and spent three years at PCC before transferring to the UA after the regents’ vote in May.

Dario is studying mechanical engineering and Danilo, electrical and computer engineering.

“In freshman year of high school,” Danilo explained, “we started reading ‘Cosmos’ by Carl Sagan, and so I began to be interested in science, mostly like astronomy and stuff. But there’s not a lot of real-life applications for astronomy, and math, too. …. So I decided to put them together, math and science, and that’s what engineering is.” He hopes to work on building sustainable energy systems in the future.

Dario is less sure of his career plans.

“Sure, I’m gonna be a mechanical engineer, but that doesn’t mean my passion is to build the biggest, I don’t know, machine ever,” he said. “I think my passion is that I have to be able to … support both of my parents and my own family when I grow up.”

Also like Huerta, the brothers had a particularly easy DACA case.

“Those years, 2007 to 2012, that I had to prove residency, I graduated high school in 2012, so I just sent my transcripts and that was it,” Dario said. “I’m just privileged to have that.”

His brother agreed, saying, “There [are] people that come here at 16 and a day, and they can’t apply.” Arbitrary cut-offs like those, Danilo argues, are “unjust.”

Proposition 300 also prevents some undocumented youth from fulfilling the requirements to apply for DACA—if an undocumented person dropped out of high school, they can enroll in an accredited GED program now to obtain deferred action. Thanks to Proposition 300, though, accredited GED programs in Arizona require proof of legal residency to enroll.

And there are others who meet the requirements but who can’t provide documentation proving as much.

“You have to remember,” Dario said, “that the folks applying for DACA are undocumented folks. …. They probably don’t have health insurance, so there’s not many medical records that they can use. If they’re working, they’re probably not working with their name, so they don’t have that evidence, either.”

After all, he pointed out, “that’s the whole nature of being undocumented.”

So while they’re pleased with the latest victory, they aren’t satisfied.

“We have to continue fighting for [all] undocumented students to pay in-state [tuition],” Danilo said.

“I think people are still celebrating, ‘Oh, we got in-state, we can all go to school,’” Dario said. “But that’s not the case at all. In-state is completely inaccessible to DACA students.”

As of January, 23,138 Arizona residents had secured DACA status. The Migration Policy Institute estimates that 32,000 Arizona residents are eligible to apply.

And yet there are only 22 students with DACA status enrolled at the UA. According to the Arizona Republic, there are 103 DACA students across all three state universities.

“That’s not because they’re not out there,” Dario said. “It’s because … there’s no financial aid from the institution, from the state or, of course, from the federal government, which makes it so that we have to pay everything out of pocket.”

The cost of two years of base undergraduate tuition and fees for residents at the UA is almost $23,000.

“I don’t know many people that can pay that amount out of pocket, even if they’re citizens or residents or whatever,” Dario said.

As engineering students, he and his brother are expected to pay even more. “Seven grand out of our pockets every semester. Who has that kind of money?” Danilo asked.

“I’m extremely lucky to be on campus right now because I’ve been saving up for about three years,” Dario said. “And I still don’t have enough to pay my last two semesters.”

He jokes that there is at least one bright spot in this ordeal. “I guess the good thing about being a DACA student is that I can never have debt,” he laughed. “We don’t really qualify for most loans.”

Dario applied and was accepted to the UA once before, in 2014, but was unable to cobble together enough funds to cover out-of-state tuition costs. The process, he said, was surreal.

“I was actually treated as an international student for many months,” he recalled. “It was so weird, because I would get these letters from the UA saying, ‘Oh, go to your nearest U.S. embassy and request this visa.’ And I live five minutes from here.”

In his third year at PCC, after being unable to transfer to the UA, Dario spent most of his time working as a tutor and saving money to move to New Mexico.

While a few states treat undocumented students even more punitively than Arizona—South Carolina, Alabama and Georgia all ban undocumented students from attending any state university or community college, no matter how much money they pay—many are better.

Twenty states offer in-state tuition to their undocumented residents. Some that don’t, like New Mexico, offer scholarships to cover the difference between in-state and out-of state tuition for undocumented students with excellent academic records.

Huerta, Dario and Danilo were all planning to move to Albuquerque to take advantage of that offer before the regents’ vote in May.

Huerta needed another year or two to save enough to finance the move and the cost of living on his own. The Andrade Mendoza brothers were nearly ready to leave.

“Arizona was going to lose taxpayers … and engineers,” Danilo said. He probably would have remained in New Mexico to work after graduation.

Instead, they are at the UA. For now. But the situation for all three is precarious.

The new Attorney General, Mark Brnovich, decided to continue his predecessor’s case, and in July he appealed Judge Anderson’s decision. It is possible that a higher court will find that there is not a DACA-sized loophole in Proposition 300, after all.

And DACA status itself is tenuous.

“I’m going to have DACA for two years,” Dario said, “and then I’m going to renew it again, and then maybe renew it again.” And during that time, Huerta and the Andrade Mendoza brothers can sleep easily, knowing they won’t be deported. “But I’m never going to get my residency or my citizenship through DACA,” he added.

Furthermore, DACA is an executive order, which means that next year’s presidential election will determine its fate and the fate of all those who rely on it. A new president will be sworn in as the semester begins in the spring of 2017, and that president can bring all three men’s lives tumbling down with the stroke of a pen.

But in the meantime, Huerta is settling into his life at the UA. He says he found a place to study in between classes, and he, Danilo and Dario are trying to start a club for undocumented students on campus.

“It’s fun,” he said of his life as a university student. “It’s chaotic.”

Guillermo Huerto, Dario Andrade Mendoza and Danilo Andrade Mendoza are all members of Scholarships A-Z, an organization that raises money for scholarships for undocumented students like themselves. You can learn more about it at www.scholarshipsaz.org.

Follow Jacquelyn Oesterblad on Twitter.