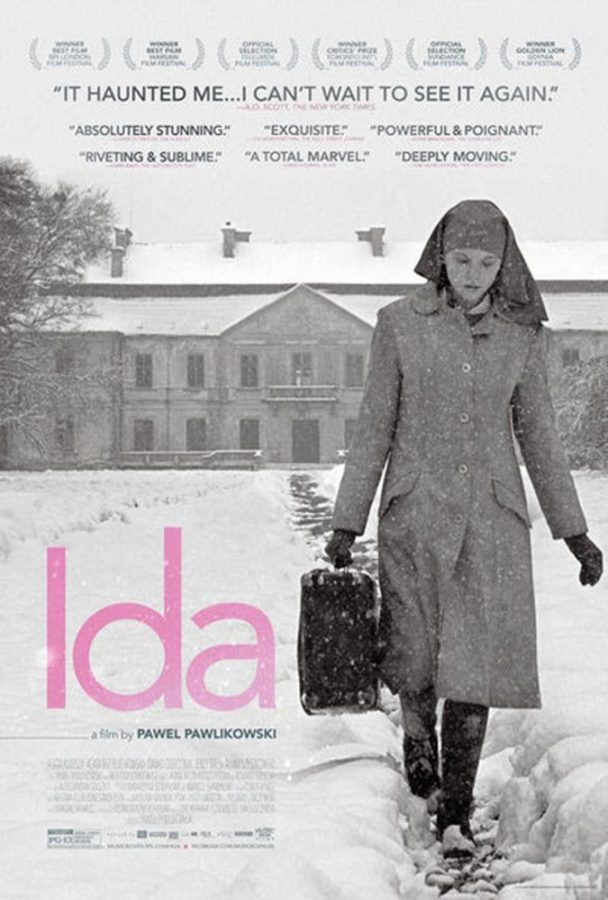

Poland has thrown its hat into the awards season ring with “Ida,” a 2013 film directed by Paweł Pawlikowski, which has accrued Oscar nominations for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Cinematography. Currently playing at The Loft Cinema, this small, intimate, black-and-white tale of a sheltered nun who must interact with the turbulent world and her wild aunt has just enough power to not be overly quiet.

Like the young nun from which the film derives its name, “Ida” is a quiet, observational film. All but the titular character’s face is covered by her habit; her wide eyes and unmoving mouth are the only portals into reading this young, enigmatic woman.

However, she does not start off as an enigma. Indeed, Ida, played by Agata Trzebuchowska, is quite the opposite: Her days are comprised of the straightforward, still rhythm of convent life in 1960s Poland. There is not much talking and even less smiling.

If it weren’t for the film’s native Polish language, it would be almost impossible to place where in the world the convent is located. It is a bastion of religion, impervious to the outside world. The girls are only shown outdoors when they erect and pray to a statue of Jesus Christ.

Our pure protagonist must venture beyond the insulated walls when she is instructed to go and meet her aunt, her last remaining relative, in order to take her vows. Before she can commit to a solitary existence forever, she must be exposed to a world that is not so structured and hushed.

The silence of the convent instantly gives way to the commotion of town life. From her vantage point inside a bus, buildings, people and cars rush by in a blur, accompanied by the noise of roaring exhaust.

Ida’s aunt, Wanda Gruz (Agata Kulesza), couldn’t be any further in character from her niece. Gruz, now a judge and a former prosecutor, has some miles on her, unlike the nubile Ida. She smokes cigarettes and drinks heavily. When Ida arrives at her apartment for the first time, a half-undressed man is putting on his pants.

It’s quickly established that the time outside of the convent is going to be particularly illuminating and challenging for Ida. One of the first bits of family background that Gruz shares with her is that Ida’s last name is Lebenstein, and that she’s Jewish — a particularly interesting religion for a nun.

As niece and aunt search for the truth about Ida’s parents, it becomes apparent how difficult it is to live in an ivory tower and then apply its principles to the real world. Surrounded by her fellow nuns, Ida had never faced any pushback, and she must be exposed to all the myriad vices, drugs, alcohol, sex and greed and still keep to her teachings. Drunk after a night out of fooling around, Gruz informs her niece that Jesus loved women of sin, like herself.

If there is one constant aspect of the film other than Ida’s absorbent gaze, it is the gorgeous cinematography by Łukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski that gently draws in the eye. Every shot is framed simply and is uninflected. The absence of color highlights what is in light and what falls into shadow.

The last shot of the film shows Ida, still in her habit, walking down a dirt road. However, the camera is no longer stationary and on a tripod; it is handheld and mobile. Ida walks forward with an immediacy and presence she previously lacked, for she is now unsure of herself and her world — forever altered.

B+

_______________

Follow Alex Guyton on Twitter.