Alex Fegan decided to tackle the big questions about religion and science in his first feature film, “”Man Made Men.””

“”One day, I just said, ‘You know what, I’m going to make this film. If I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it,'”” said Fegan, who worked as a corporate lawyer in Dublin, Ireland, for four years.

In “”Man Made Men,”” Irish scientist Benjamin Ezekiel is attempting to create life from inorganic material in an effort to prove that God does not exist.

I talked with Fegan over the phone after he returned from a tour of the UA’s Center for Creative Photography on Friday. He had just flown in from Ireland to appear at the screening of “”Man Made Men,”” which made its U.S. debut at The Screening Room, 127 E. Congress St., last Saturday as part of the 2011 Arizona International Film Festival.

Can you briefly describe the film?

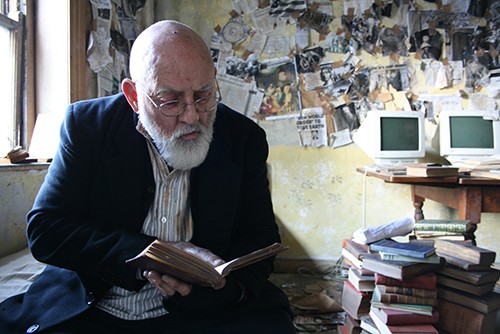

It’s about an Irish scientist, Benjamin Ezekiel, who tries to make life forms from lifeless materials, and then watch them grow and evolve inside a sealed chamber in his lab. Meanwhile, an old reclusive man hears about the experiment and he believes it will cause the end of the world. So he sends three rabbis to Ireland to try and stop the experiment. Then the rabbis realize that Benjamin is being protected by powerful forces who want to see the experiment completed.

Where did the idea for this film come from?

It was inspired by two American scientists, one was called Stanley Miller, who in 1953 tried to make life from lifeless materials. He failed. But in May 2010, a scientist called Craig Venter (founder, chairman and president of the J. Craig Venter Institute), he actually claimed that he was the first scientist to make life from lifeless materials. So I was looking at these guys and for some reason, I had this idea that the day that man makes life, shortly afterwards it would lead to the end of life for man. So there would be something cyclical about the idea that when man makes life, it would result in the end of life. It’s kind of like the final step in our evolution. It would be almost when we become God, that’s it. It would lead to the end.

Is the film comical or serious?

It’s serious. The film looks at the philosophical consequences of man playing God. The idea was that we’re moving forward technologically, but sometimes we don’t think about what it actually means when we achieve certain things, such as the creation of a synthetic genome or the creation of a synthetic organism. What does that actually mean for us? What does that say about us as humans? Who made us? Could they be a god or are they just a more advanced human doing something similar to what we’re doing? So it’s a serious film, I suppose. There are some funny bits though.

How long did it take to complete this?

It took about three years, from when I started writing the script to when we finished editing, mainly because we were working full-time and there’s also stop-motion animation in it as well, which takes a lot of time.

I saw that you had an incredibly low budget for “”Man Made Men.””

Yeah. The entire budget that we spent on it was about 4,000 euro (about US $5,700).

What were some of the biggest hurdles in making this film?

I think the biggest challenge that we had was just deciding to start. Then once that happened, I think things started to fall into place. People started getting on board and wanting to help out. We managed to get a big choir to do the soundtrack with us, and they worked for nothing. All the cast helped us out and gave their time up for the cause. Probably the biggest hurdle other than just getting started was filming inside certain locations. We filmed inside Ireland’s main court building, the Four Courts in Dublin, and not even big films can film in there. But with my legal background, I was able to persuade them to let us film in there for a day. So we shot a court scene inside that building. (Laughs). It’s a bit of a challenge.

How have people reacted to the scientific and the religious elements in “”Man Made Men””?

The idea was to look at that conflict between science and religion, but then to see that actually the two of them are more intertwined and interrelated than most people realize. In Ireland, the general reaction, I would say, has been one of real interest. When we started, I was thinking that it would be quite controversial, because the scientist, in his aim to make life from lifeless materials, he’s trying also to prove that God doesn’t exist. But people just seem to go, “”Oh, that’s interesting.”” They look at us not necessarily as an argument that’s being put forward, but just as a narrative that is taken place in the story. So it’s more of interest than controversy or outrage.

Do you have any advice for other aspiring filmmakers?

Yeah. Just do it, don’t think about it. Don’t listen to naysayers because all of the technology is available now. If you have a story that you want to tell, it’s very, very straightforward to get it done. The editing equipment is readily available. Everything’s so affordable, so there are no excuses anymore. It’s just about persevering and then getting it out and not to worry too much.