Dear Editor,

In the fall of 1997, I thought my parents were paranoid when they warned me about being recruited into a religious cult when I arrived at college. My father, a Mennonite pastor for over a decade and then-prison chaplain, had provided stacks of books over the years about defending the Christian faith. Having converted at the age of 16 and given this intensive religious upbringing, I felt like they were making a big deal out of nothing — cults were something that only fringe weirdos joined to live in seclusion and worship the god of taxicabs, or some other such nonsense — it’s certainly not something a kid with a firm faith pursuing a college education in psychology could be taken in by.

However, I did fall in with a high-functioning cult that was recruiting on campus and remained with them for 24 years. On this year, the 25th anniversary of first attending the University of Arizona, I thought it would be helpful to share the benefit of my experience and some tips for how students can learn from my mistakes.

So, the question is: how can students tell the difference between real spiritual counselors who want to assist them in their personal journeys from the cultists looking to take their time, money and sense of self?

First, like any other subject: students need to do their “homework.” The University Religious Council has a page on the Dean of Students site with “red flags” describing the signs to look for from destructive cults. This is a great resource for looking at extreme examples of high-control behaviors and may contain known offenders to avoid.

Second, there is a faster way to determine if the group is genuine: ask the right questions upfront. I advise treating it like choosing a major. No one wants to get seven classes in only to discover that they hate it, so they’ll need to do a little legwork first.

Here are some “green flags” to look for:

The religious group has a clean Google search. If searching “[church name here] Tucson” in quotation marks, Google should generate reviews and testimonials from people who’ve attended. If it shows scathing scandals in the news or a social media presence warning people away made by former members, students should avoid the organization — especially if they cite the aforementioned “red flags.” If available, talk to some former members about their experiences, especially if there are concerns. Just like talking with people who left a major, it can provide a lot of insight into the challenges and whether it’s a good fit.

The church or religious organization is financially transparent. Healthy groups regularly and proactively communicate their charitable giving, the recipients and the amounts. These groups are eager to share the great things that they’re doing and don’t hide spending, salaries or assets — the average member should have a very clear financial picture of what the group supports and how it ties to the ministry.

Pro tip: Students should never just take a recruiter’s “word for it” – communicate directly with the office, in writing/email/phone and expect an acknowledgment in return. Donors have rights.

They are well-respected in the community and have multiple connections with similar local ministries. Current members should quickly be able to identify who these partners are, and those partners speak well of the group and cooperative activities.

Prospective members are treated with respect. Respect differs from “love-bombing” (where they’re flattered, praised and showered with attention) in that recruiters respect student boundaries — like not soliciting their contact information, not pressuring them to make decisions about joining or giving money and being patient with their spiritual inquiries rather than pushing an agenda. A quick test is simply for the student to ask about the organization’s history, finances and accountability structures as outlined above; if the organization is more interested in getting the student to reveal their personal information than sharing their own, it’s a yellow or red flag.

They don’t mind if students are prioritizing their schoolwork, family or friends first. Healthy organizations are not easily threatened by competing commitments; they recognize that students are here to study and are individuals with full, productive lives. These groups will try to expand their attention, not demand it or command it.

There are many constructive spiritual organizations that are eager to help students on their faith journeys. I encourage students to study the red flags and search for the green ones — they’ll find that this exploration is an enriching dimension to their college experience.

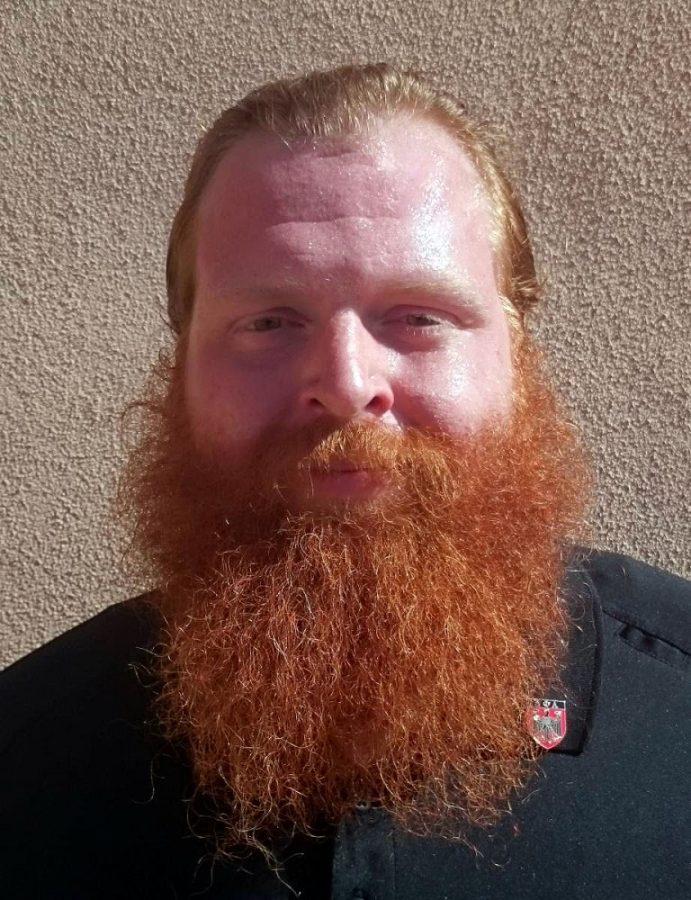

– Andrew Winslow graduated from the University of Arizona’s PhD program in Rhetoric, Composition and the Teaching of English in 2009 and is a manager for company career development programs and initiatives at Raytheon Technologies. He is currently writing a book about the emerging “high-functioning cult” phenomenon in the United States.

Have something you want to say? Send your “Letter to the Editor” to editor@dailywildcat.com to be considered for publication.