Communication is key. Take relationships, for example. When communication breaks down, the results can be cancerous.

Like in society, communication between the cells of our body is critical, as Janis Burt, a professor of physiology at the University of Arizona, discovered in her lab.

Burt’s laboratory, located in the Medical Research Building, studies a class of proteins called connexins which are responsible for communication between all our cells, but that just scratches the surface of their roles.

RELATED: ‘Marriage’ of ideas: husband and wife team-up to combat opioid epidemic

“Think of connexins being like a cell phone. Their primary purpose is communication from one person to another, but modern phones have apps that allow them to do many other things in addition to communication,” Burt said. “In our bodies, connexins do many other things in addition to communication, just like the apps on our phone.”

In the cells of the vascular system, which is responsible for carrying blood throughout the body, a specific connexin protein, connexin 37, communicates to surrounding cells and tells them not multiply to maintain the structure of the system. When this cell talk is disrupted, cancerous tumors can hijack the system and direct more and more resources their way as well as open up highways of movement around the body.

Yet, some of connexin 37’s functions could also be harnessed as a tool to fight cancer, according to Burt.

“The data we have available for connexin 37 suggests that specific forms of the protein can induce cell death or suppress growth. Both of these functions could be useful in combating cancer,” Burt said.

One of the key concepts of biology is that the function of proteins, otherwise thought of as our cellular machines, are determined by their structure.

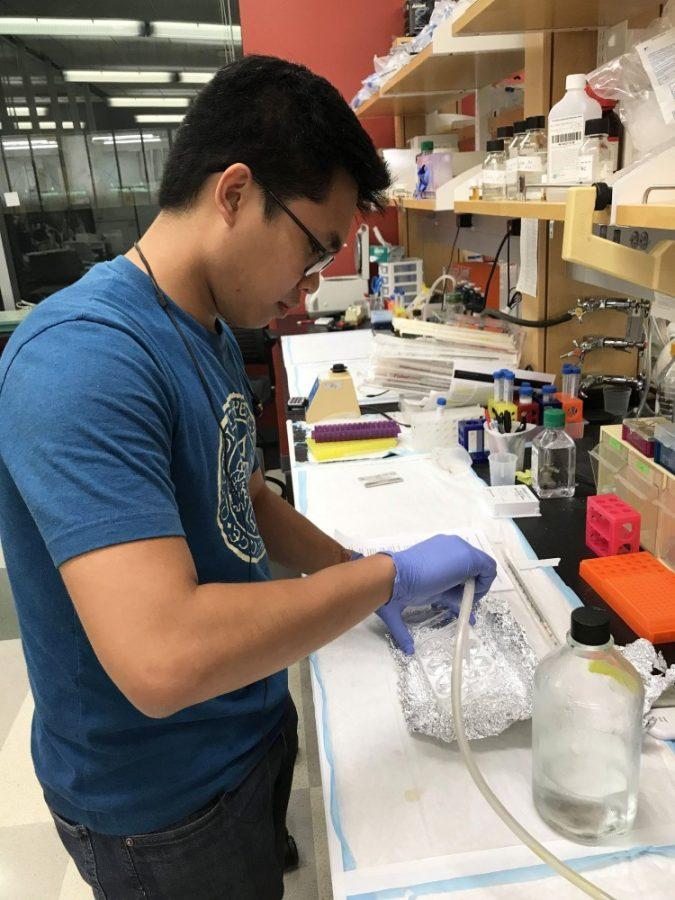

For Andrew Alamban, a molecular and cellular biology junior, the structure of connexion 37 has driven his research in the Burt lab for the last year.

One of the most common ways to change a protein’s function is to change its structure. Our cells do this all the time, not by making new proteins, but rather by attaching a molecule called a phosphate to already created proteins, according to Alamban.

“We have lots of data indicating that function of the full-length connexin 37 protein is modulated by whether and where its tail structure is phosphorylated,” Alamban said.

According to Alamban, this pattern of phosphate attachment could be thought of as a switch. One pattern for connexin 37 could potentially suppress cancer growth. An alternative state could be used to help heal wounds.

Additionally, Alamban is examining other ways connexin 37 could change in its structure. For example, one question Alamban is asking is: Does a shorter form of connexin 37 have independent and unique functions?

With all this data in mind, Burt said she believes connexin 37 can be engineered to serve our particular needs within the body. By changing its structure and delivering it to specific cells, connexin 37 could be developed to fight cancer and more.

Engineering connexin 37 will not necessarily be easy. It will take hard work and creativity. Over 35 years into her research at the UA, Burt has found working closely with undergraduates like Alamban is invaluable to this process.

“Undergraduates have different ways of looking at things and help me think outside of the box,” Burt said.

According to Burt, they are smart and talented, but, more importantly, they ask questions that change her way of thinking.

RELATED: Annual Undergrad Biology Research Program brings together minds, bodies and souls

For Alamban, having the chance to work in a lab has positively impacted his college career, even helping him discover his passion for science and research.

“I initially thought going into medicine was the only way for me to make a significant impact on people’s lives. However, my science courses and lab experience have taught me that the field of research has a similar impact and comes with … a great sense of discovery as well,” Alamban said.

While researching the necessity of cell communication, the benefits of communication between mentors and students seems to have also found its way into the data.

Alamban and Burt’s research has been supported by UA’s Undergraduate Biology Research Program, the National Institutes of Health and the UA College of Medicine.

Follow Randall Eck on Twitter