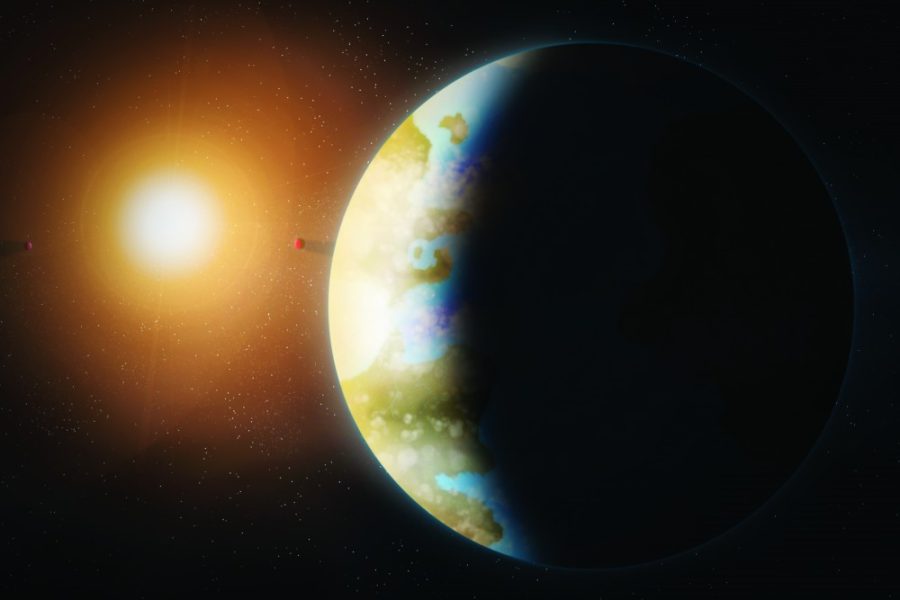

An Earth-sized planet was recently discovered orbiting in its star’s habitable zone, confirming for the first time that planets similar to Earth can exist close enough to their stars to house liquid water.

Discovered using NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, the planet joins Earth as the only other known planet orbiting its star in what astronomers refer to as the habitable zone.

Based on the star’s luminosity, the habitable zone is the distance a planet would have to be from its star in order for the average temperature to be above the freezing point of water and below the boiling point of water, allowing water to exist as a liquid, said Tom Fleming, a lecturer in the UA astronomy department.

“We want to know the statistics of planets in the habitable zone so we have some idea about how common potentially life-bearing worlds may be,” said Josh Eisner, an associate professor in the UA astronomy department. “From that statistical point of view, it’s very interesting.”

According to NASA, the planet, known as Kepler-186f, is located approximately 500 light-years away in the Cygnus constellation. While the planet is similar in size to Earth, the star it orbits is vastly different from the sun. As a red dwarf, the star is much dimmer than our sun, meaning that the habitable zone of Kepler-186f is closer to its star than Earth is to the sun.

“Its habitable zone is by definition going to be closer to its star because it isn’t as hot or as bright a star,” Fleming said. “In order to be warm enough so that water melts but not too hot so that water boils, you need to be closer to the star.”

Because of this closer proximity to its star, Kepler-186f orbits its sun once every 130 days, as compared to the 365-day orbit of Earth.

But while astronomers are now aware of the planet’s size, they don’t yet have a way to calculate the mass or determine the composition of the planet. Due to the similarity of its size to Earth’s, many theorize that the planet could be rocky, though astronomers have no way to determine if this is true.

Given the intense curiosity surrounding exoplanets, scientists will likely find “clever” ways to learn more about the new planet, said Don McCarthy, an astronomer at the UA.

“But right now,” he said, “all we know is the physical size.”

While the discovery of the planet marks a significant milestone for astronomy, the search for exoplanets is not a new undertaking for researchers. According to NASA, 1,706 planets have been discovered, and Kepler has found 3,845 planet candidates during its five-year run.

The Kepler telescope was specifically designed to locate Earth-sized exoplanets throughout the Milky Way using a technique known as the transit method, which measures the dip in a star’s brightness caused when a planet moves in front of the solar surface and blocks the light during its orbit, said Eisner.

While this technique is good for space-bound telescopes, the large telescopes on Earth use the radial velocity technique to measure the shift in spectral lines from a star brought about by the presence of a planet.

Along with these detection methods, astronomers at the UA are investigating direct imaging techniques, which specialize in finding exoplanets that have more distant orbits from their star. The direct imaging techniques help detect planets that other methods of exoplanet detection don’t catch, which allows astronomers to compile statistics about the distribution of distant-orbit exoplanets, said Katherine Follette, a graduate student in the department of astronomy.

While Kepler-186f marks a milestone in the search for exoplanets, many scientists are simply happy to finally have proof that the Earth is not a unique planet in the universe.

“It’s one thing to make a philosophical argument; it’s another to have definite evidence,” Fleming said. “Now we can actually say that Earth is not unique. There are other planets that can be around stars where water can exist as a liquid. We’ve been saying it’s probably true, but now we can say that it is true.”

—Follow Michaela Kane @MichaelaLKane