About halfway through Gaspar Noé’s new film “Love,” the camera cuts to an extreme close-up of the protagonist’s erect penis, holding that shot until the character climaxes, ejaculating, in 3D, out into the audience.

I headed for the lobby after this, not because I was offended by the film, but rather because that shot reminded me that I needed to go pee really badly. After relieving myself in the bathroom and heading back toward the theater, I ran across two older gentlemen depositing their 3D glasses into the bin and heading for the front door.

“That movie really stinks,” they grumbled to the lovely student employee in charge of concessions for that auditorium. She smiled back tactfully.

I, however, frowned, annoyed at the arrogance of condemning a film by one of France’s greatest living directors after having only viewed the first half. I sat through the whole thing, and it actually kind of did stink, but that’s not the point.

The point is that far too many filmgoers expect films to conform to traditional Hollywood entertainment standards, and anything that doesn’t fall into this category is written off as trash.

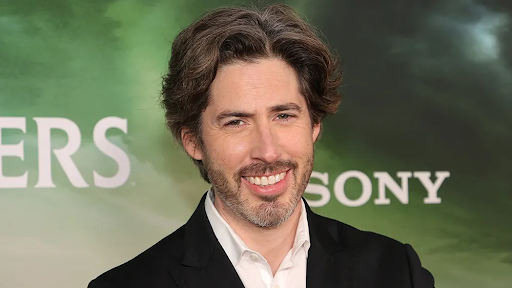

Jeff Yanc, program director for The Loft Cinema, where the aforementioned screening was held, urges cinemagoers to look for more than just entertainment in their film consumption.

“Culturally, we’ve become very attached to the idea that if a film makes us feel something other than happiness, it must have failed,” he said. “I think a ‘good’ film is one that effectively achieves the specific goals it has set out to achieve, whether those goals are to entertain or to enlighten or to shock, etc. If a film is deliberately trying to upset you and you leave the theatre feeling angry, the film has succeeded on some level.”

In an interview with Vulture, Noé describes his new film as “mostly arousing on a sentimental level,” an attempt to recapture the more sensual erotica of eras gone by. Viewed through this lens, “Love” still really doesn’t hit the mark.

To be fair, I find it difficult to be aroused by any film when sitting in a theater, surrounded by strangers and one of my professors. So it may have just been me. Regardless, I can now judge the film with far more agency than those two quitters who left the theater in a huff.

And, as Yanc puts it, even sitting through a film that you ultimately hate is a useful experience.

“There’s no guarantee that you’ll love every film you see, nor should there be,” he said. “Part of the fun of being a true cinephile is taking chances on films that may confuse or disappoint or infuriate you, as this can make you appreciate the films you truly love all the more.”

Indeed, two hours of irritating French lovers yelling at each other and then having aggressive make-up sex made me long for the simple pleasures of Han Solo being sucked into the carbon-freezing chamber or Ellen Ripley taking a flamethrower to some aliens.

Most of my viewing at The Loft Film Fest 2015 would certainly fall into the “experience” category rather than “entertainment.” I purposefully sought out films with somewhat exotic premises, and while none of them could be described as an exhilarating roller coaster ride, all of them left an impression on me as both a cinemagoer and a filmmaker.

Americans could certainly benefit from more of this type of viewing, not only to expand their artistic horizons, but also to expose them to various cultural points of view that might otherwise go unexplored. It’s harder to be intolerant of a social group that you’ve seen a heart-rending, two-hour drama about.

This is the true power of cinema — its awe-inspiring, intangible ability to influence our world just as much as we as storytellers influence the fictional one. For a more enriching, if not necessarily thrilling, cinema experience, filmgoers might consider making their next viewing a challenging one.

To quote Yanc once more, “Even if you end up not loving a film, the chances are pretty good that the experience is not going to kill you. So why not give it a shot?”

Follow Greg Castro on Twitter.