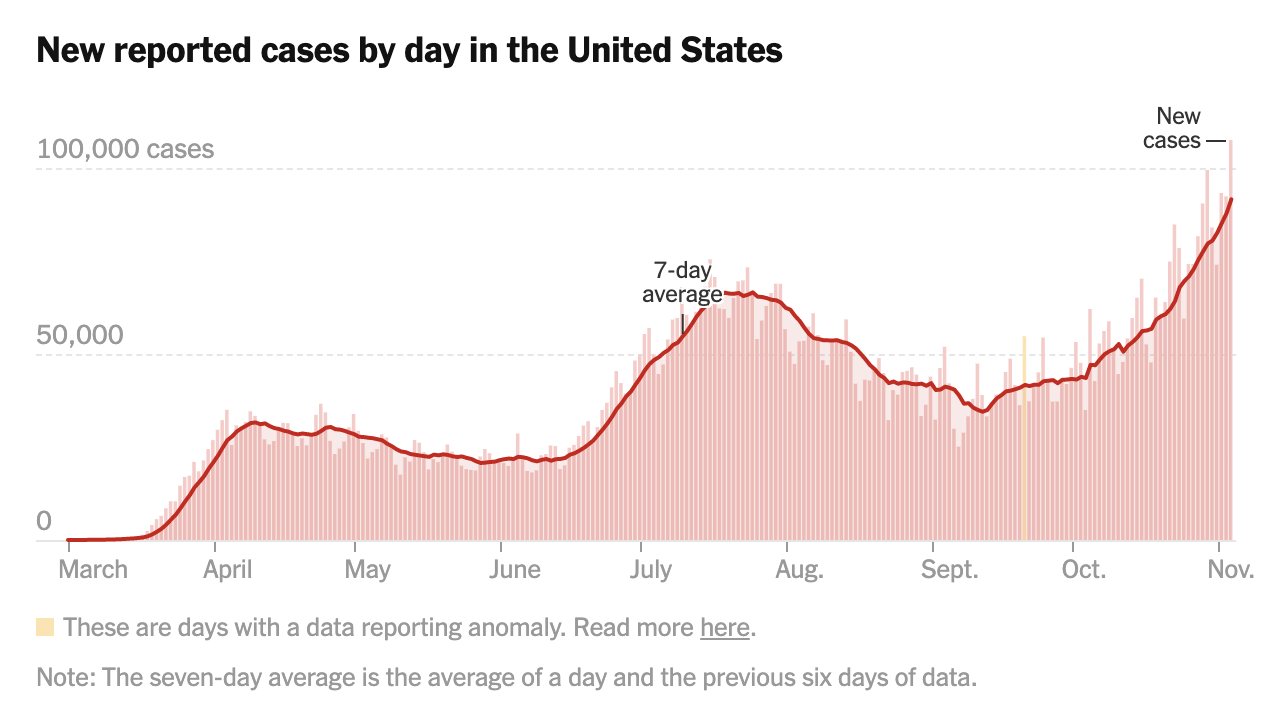

As the country remains eager to find out who will become the next president, concerns of a “deadly phase” of the pandemic loom over public health officials and frontline workers. On Wednesday, Nov. 4, the country reported over 107,000 new coronavirus cases, an all-time record since the beginning of the pandemic, according to The New York Times.

Source: New York Times

A few weeks ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first treatment for COVID-19: an antiviral drug called remdesivir that received an emergency use authorization earlier this year in May. The drug has mixed results, with some studies showing a reduced length of stay in hospitals for patients with severe illnesses while others showing no significant benefits.

“The drug appears to help some patients recover more quickly but it hasn’t been shown to improve survival chances,” said Will Humble, the executive director of the Arizona Public Health Association. “The medicine is only approved for COVID-19 treatment if it’s administered in a hospital or other acute inpatient care facility.”

RELATED: Tohono O’odham Nation donates money to Arizona universities for COVID-19 research

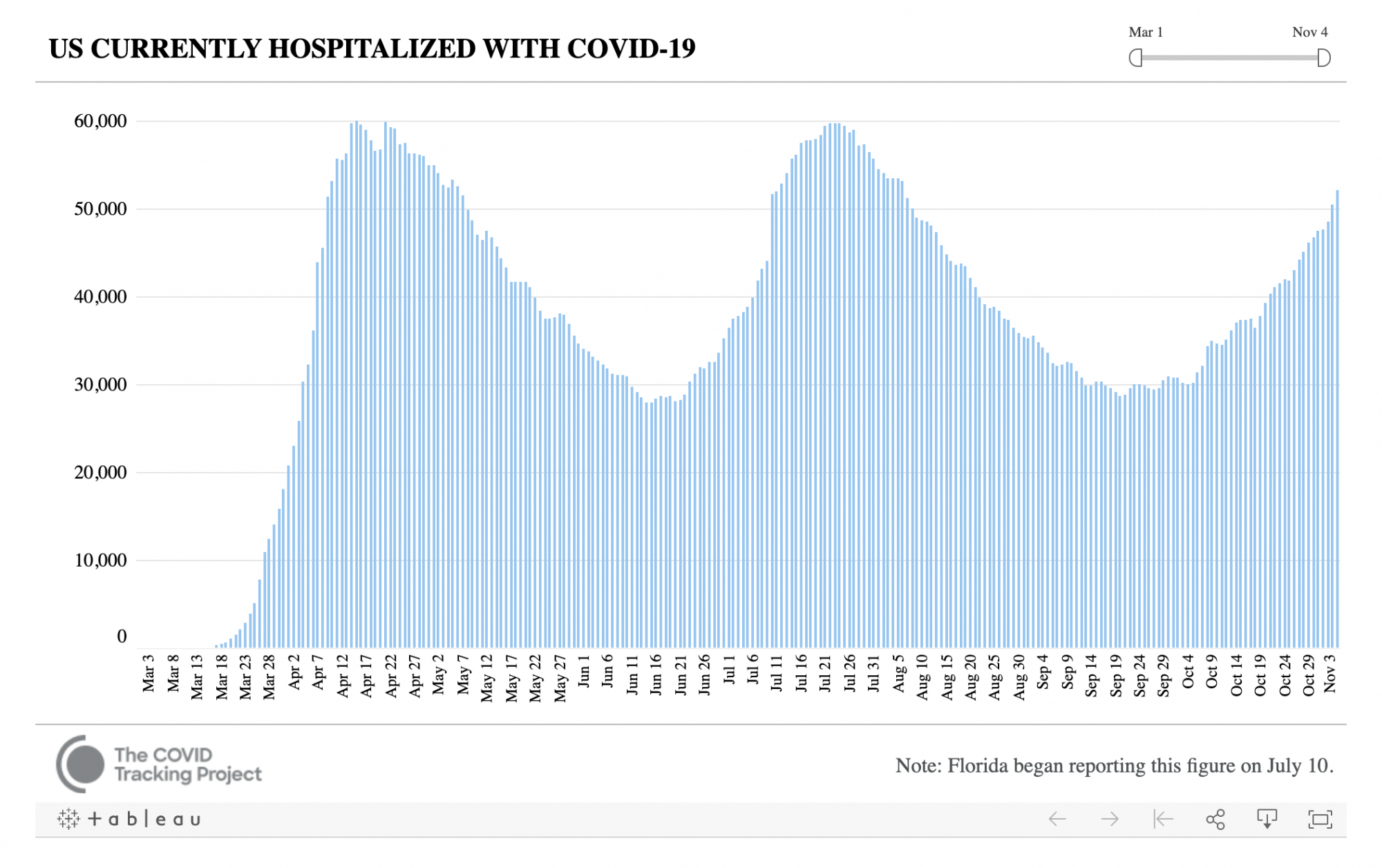

Despite claims that coronavirus cases are only on the rise because of a rapid increase in testing nationwide, the United States is also seeing a sharp increase in the number of hospitalizations. The number of hospitalizations from the coronavirus hovered around 30,000 for the majority of September; however, the U.S. is now seeing close to 60,000 hospitalizations per day.

Source: The COVID Tracking Project

A recent study out of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai found that more than 90% of mild-to-moderate cases of COVID-19 still produced a robust antibody response. To assess how these antibody levels persisted over time, the researchers randomly selected 121 participants in the cohort of over 30,000 people with mild-to-moderate symptoms to follow up with a range of initial antibody levels.

Although antibody levels had declined a small amount, the people in the group were still at least at a moderate level of antibodies, even five months after initial testing.

“The serum antibody titer we measured in individuals initially were likely produced by plasmablasts, cells that act as first responders to an invading virus and come together to produce initial bouts of antibodies whose strength soon wanes,” explained Dr. Ania Wajnberg, director of Clinical Antibody Testing at the Mount Sinai Hospital and first author of the paper.

At a time of heightened uncertainty across the country, researchers are discovering mixed news — both good and bad — about the pandemic. Despite rising cases and hospitalizations in virtually every state in the country, the fact that antibody levels persist for months after infection provides hope for longer-lasting immunity.

Follow Amit Syal on Twitter