While it’s certainly important to never presume guilt in any situation, whether that is in the realm of popular opinion or a court of law, it’s more than safe at this point to accept that Bill Cosby is every bit the sex criminal he has been accused of being for over a year now. The Associated Press reported July 6 they had obtained court documents from 2005 in which Cosby confesses to not only purchasing Quaaludes, but to using them on at least one woman.

This is likely a lie of omission; more than 30 women have accused Cosby of assault since 2014. With the dates of these alleged assaults spanning decades, it’s hard to see the comedian as anything other than a serial rapist. As prosecution is unlikely, the victims’ only consolation will have to be the knowledge that the former “family man” will now go down in history as a pervert and a hypocrite.

And while it’s hard to imagine any young college students reading this article being particularly torn up over the loss of innocence when it comes to the Cosby legacy—as Amy Schumer put it in a recent sketch “the next time you put on a rerun of the ‘The Cosby Show,’ you may wince a little,”—this story once again begs the timeless question: Can we separate the art from the artist?

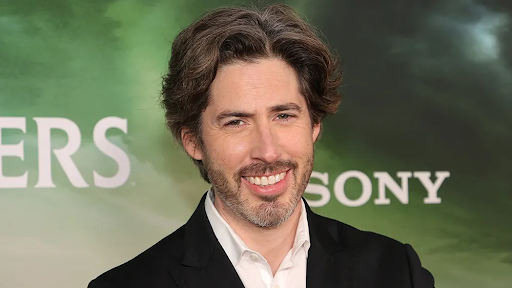

Not two years ago, the public was grappling with the same issue as The New York Times ran Dylan Farrow’s scathing “What’s your favorite Woody Allen movie?” column. In that piece, Farrow urged not only fans but also the actors involved with the director to consider that support of his works is tantamount to tacit acceptance of his history of sexual assault. Rarely has the line been so clearly drawn in the sand.

And yet, as a film student, I find this dichotomy somewhat difficult to accept. Freshman coursework at any film school requires study of such classics as “The Birth of a Nation” and “Triumph of the Will,” which were respectively directed by a flaming racist and, you know, a Nazi. Not only this, but those films actually promote the horrific agendas of their auteurs. For those unfamiliar, “The Birth of a Nation” follows the “heroic” exploits of the Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction era South, and Triumph is 114 minutes of why you should join the National Socialist Party.

At least when you watch “Annie Hall,” at no point does a character turn to the screen and suggest that maybe you should go out and rape someone. Allen’s films, regardless of his personal legacy, represent the pinnacle of 1960s-’70s New Hollywood cinema and feature themes of anxiety, loneliness, depression and longing that appeal to all generations. Along with Coppola, Lucas and Spielberg, Woody Allen made Hollywood cool again.

“The Cosby Show” can claim no such profound legacy, though it was progressive for its time. Are black Americans who grew up watching Cosby in the ’80s, feeling inspired by its depiction of a successful African-American family, now supposed to feel ashamed of those memories? Can they not remember the program for what it was and leave its star’s horrible history out of the equation?

To be clear, I’m not demanding that anyone go out and make a point of watching any of these now-controversial works. If the presence of a controversial personality or controversial subject matter proves distracting, there are of course many equally worthwhile alternatives in any medium. And, as mentioned before, it’s doubtful that any of us were planning on marathoning “The Cosby Show” sometime soon anyway. In any case, it may be worth reexamining the “baby with the bathwater” approach when it comes to these troublesome legacies. While the actions of these men will never be excused, their works remain significant.