In what Arizona law experts called a rare moment of public reflection from the U.S. Supreme Court, Justices Antonin Scalia and Stephen Breyer appeared yesterday for a discussion of their methods for interpreting the Constitution.

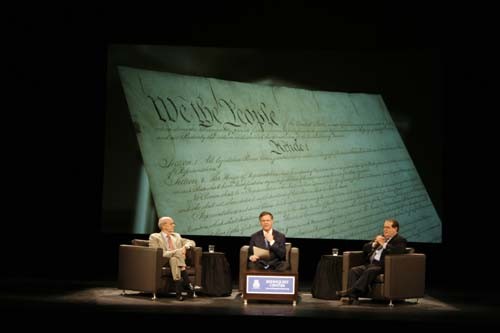

The discussion, hosted by the James E. Rogers College of Law’s William H. Rehnquist Center, was held at the Tucson Convention Center’s Leo Rich Theater and broadcast live on the Public Broadcast Service in Arizona. At the event was a full house of Tucson community members, UA law students and faculty, and administrators including President Robert Shelton and Regent Ernest Calderon, a UA law college alumnus.

NBC justice correspondent Pete Williams moderated the discussion — titled “”A Conversation of the Constitution: Principles of Constitutional and Statutory Interpretation”” — and asked the justices questions about their approach to the Constitution.

Scalia and Breyer voiced sharply opposing viewpoints that stem from a philosophical dichotomy between, in Scalia’s words, “”originalism”” (Scalia) and “”evolutionary interpretation”” (Breyer). The difference, the justices said, is that an originalist attempts to interpret constitutional statutes based on the intentions of their authors while an evolutionist attempts to describe how older values apply to present-day circumstances.

Scalia looks for an “”original intention,”” while Breyer is “”more of a guy who says, ‘let’s take a broad view,'”” explained Tucson criminal attorney and event attendee Gregory Kuykendall.

The justices focused their debate on whether the ideological values behind a given statute of the Constitution were acceptable grounds for a judgment, each citing past Supreme Court cases to substantiate their opposing views.

As soon as the literal text of the Constitution is sidelined in favor of a more subjective approach, Scalia said, the possibility of reaching a fair judgment is seriously mitigated.

“”There are no answers (in evolutionary interpretation),”” Scalia said. “”Zero.””

Reading out of his trademark pocket Constitution, Breyer countered by saying that lawmakers write laws with the intent to enforce a certain societal value, which it is the task of justices to uphold in the present day even if the details of a case may not have been accounted for.

Breyer gave the example of a hypothetical sign in a city park reading “”No Vehicles.”” If a monument for veterans was built at the park out of an old Jeep, an exception to the rule could be made because its authors had a certain objective in mind that would not be compromised by the monument.

UA law professor Andrew Silverman said that although the event did not change his mind about any legal approaches, it still provided an unusual glimpse behind the scenes of the country’s highest court.

“”It’s really unique that two justices are willing to express their opinions in this kind of forum,”” he said.

Several law students at the event said the discussion shed light on the people behind the black robes.

“”It solidified my perspectives on both justices,”” said first-year law student Brynn Gruenberg.

First-year law student Amanda Abeln had a slightly different take.

“”(Scalia) seems like more of a human after today,”” she said.

The distinction between the justices can perhaps be best summed up by Williams’ final question, which was about whether there is a place in judging for moral values.

“”No,”” Scalia said.

“”Yes,”” Breyer said.