Stories of strange and miraculous births go at least as far back as the ancient Greeks. According to their myths, Zeus felt threatened by the idea of bearing children that may rival his position of power. When his wife Metis still managed to conceive a child through fate, Zeus decided to swallow his pregnant wife in an attempt to keep her and the child prisoners of his belly. Eventually, Zeus’s forehead split and out sprung his full-bodied, armor-clad daughter, the goddess Athena Parthenos. Since Zeus technically bore his daughter, he was considered the lone parent.

This fantastical story of Zeus and his descendents illustrates the idea of parthenogenesis, or asexual reproduction.

Parthenogenesis is not merely the stuff of myth. No, children bursting from the foreheads of their human fathers won’t be a common occurrence any time soon, but if one looks beyond the gods of myths, one will find that parthenogenesis is actually happening in the world around us.

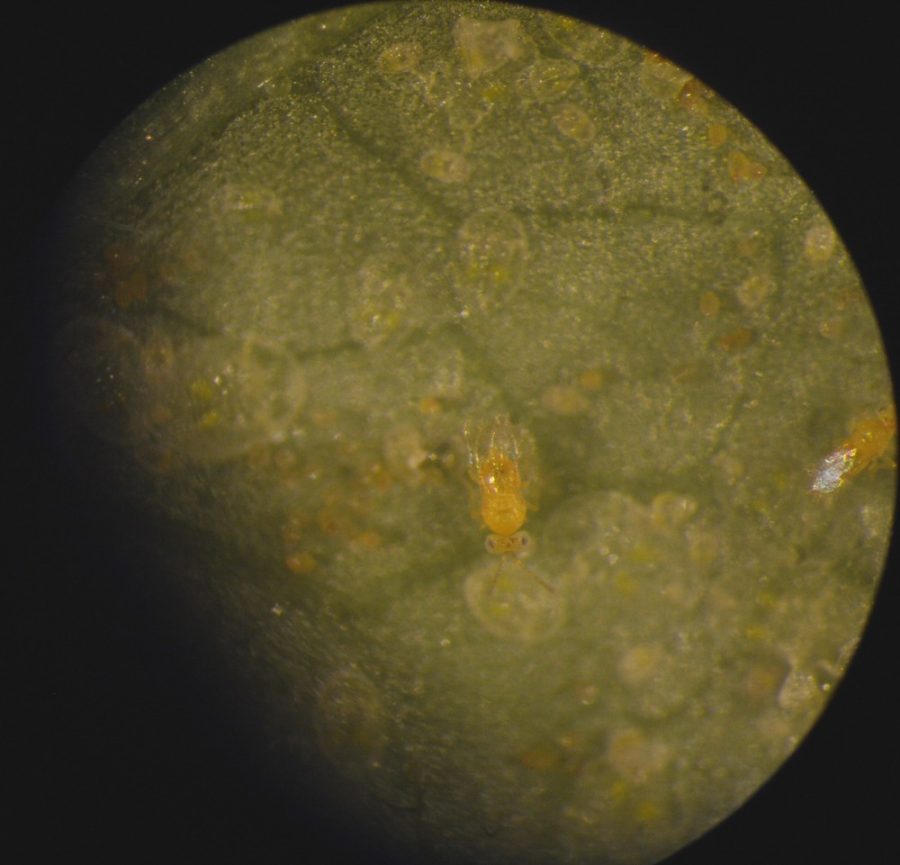

At the UA, it’s happening everyday in the Hunter Laboratory, headed by Dr. Martha S. Hunter from the department of entomology.

Just as humans carry bacteria in our guts, a species of wasp (Encarsia inaron) carries the Cardinium bacteria that has some powerful gender-changing abilities. Unlike the transmission of bacteria among humans from host to host, called horizontal transmission, these wasps transmit their bacteria vertically, solely from mother to offspring.

In E. inaron wasps, female wasps carry two sets of chromosomes, while male wasps carry only one set of chromosomes. Like humans, female wasps have two identical sets of all of their DNA bundles, called chromosomes, while male wasps only carry one copy of all of their DNA. Normal, uninfected female wasps lay eggs with one set of chromosomes. When male wasps fertilize these eggs, they develop into healthy female offspring with two sets of chromosomes.

When a female wasp carrying the Cardinium bacteria lays an egg with one chromosome, it should become a male, but the bacteria causes the number of chromosomes in the egg to double. Therefore, this new wasp offspring has two chromosomes, and subsequently develops into a female.

So what does this mean in terms of parthenogenesis? Ultimately, the ability for the bacterium in the female to usurp the male reproductive role of doubling the eggs’ chromosomes and creating more female offspring renders the need for male fertilization unnecessary.

“Males for this species are a complete dead end,” Hunter said.

When the entire population is infected with this bacterium, the whole species is then female. Furthermore, Hunter explained that evolutionarily, these male wasps have lost their function due to their lack of reproduction, which causes this species to be endangered and dependent on its bacteria.

Among other things, Hunter and her research team are working to uncover the genetic basis and molecular mechanism through which this parthenogenesis induction operates. While the Cardinium bacteria being studied in Hunter’s lab is lesser known, there is a more commonly known bacterium named Wolbachia, which plays the same type of role—although the two are unrelated.

Studying these two unrelated, yet eerily similar, bacteria in conjunction will help in “understanding a little bit about how evolution has been working in parallel to do these types of things, “ according to Hunter.

Ultimately, while the clear origins of this evolutionary history have yet to be determined—much like the Greek mythology—one thing can be decided: wasps with bacterium in their bellies are much like Zeus, the bringer of parthenogenesis.

Follow Lena Naser on Twitter.